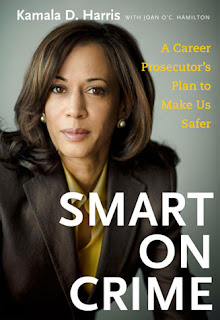

Kamala Harris’ new book, Smart on Crime: A Career Prosecutor’s Plan to Make Us Safer, written with Joan O’C Hamilton, is a refreshing book on prosecutorial practices, and on the need to disengage law enforcement from practices of severe sentencing and mass incarceration.

In the book, Harris, who is the San Francisco District Attorney, and running for Attorney General, speaks up about her prosecutorial philosophy, but also discusses more broadly America’s criminal justice priorities.

The book opens with an examination of several “myths about crime”. Harris seeks to situate the crime debate outside the partisan lines, pointing out that there is an alternative transceding the “tough/soft on crime” dichotomy. She also debunks the idea that there are no alternatives to current correctional techniques by examining a series of innovative reentry programs. The novelty of this account lies in the fact that these programs are sponsored by law enforcement – prosecution offices and sheriff’s offices.

While Harris treats crime and victimization very seriously, she emphasizes the fact that violent and sensational crime constitutes a small percentage of the entire crime picture. The universe of nonviolent offenders, who are not as much of a danger to society, will not be properly handled using lengthy prison sentences, which contribute to recidivism.

Harris suggests an expansion of the traditional prosecutor’s role, arguing for including reentry projects and community involvment in the scope of prosecutorial responsibility. One issue in particular that she highlights is the need to address school truancy. As Harris explains in the book, she sees truancy as a major predictor of a criminal career, and therefore believes that addressing education, and making sure children are not truants, will go a long way toward preventing crime in the long run. The District Attorney’s office’s efforts in this regard have already yielded a decline in truancy rates in San Francisco. Nevertheless, the question is whether criminalizing the truants’ parents is a truly effective measure in reducing crime. In adopting this measure, Harris may have fallen into the same trap she warns us about in the book – focusing on criminalization rather than on problem solving.

The book is meant for popular readership, and much of the rhetoric (including examples of violent, dangerous offenders whom Harris has helped remove from the streets) will soothe readers who are concerned about violent crime and victimization. These sections do not read as a fake attempt to placate the masses so that a “soft on crime” agenda will remain unnoticed. As a prosecutor, Harris comes off as committed to law enforcement and genuine in her belief that some offenders need to be removed from society for a long time. It is precisely this genuine perspective that lends credibility to her “smart on crime” argument, which comes from a concern for public safety in the broader sense rather than from pity. This decidedly not-soft-on-crime stance is enhanced by Harris’ humonetarian arguments for her “smart on crime” solution, which is advocated as a means to save money as well as achieve more public safety.

Prison scholars and inmate rights’ activists who read the book may be concerned that Harris does not go far enough. I do not see this as a shortcoming in the book. Harris is a prosecutor and she writes from a prosecutor’s perspective. Even under a more benign, less punitive correctional regime, law enforcement officials and prison activists will not see eye to eye. The important thing is that this book opens the door for open minded prosecutors to transcend the government/offender divide, and more importantly, the right/left divide, and to agree on general solutions, the most promising of which is a focus on reentry programs such as San Francisco’s Back on Track program. This program, which uses deferred entry of judgment as a “test period”, under the D.A.’s office supervision, combined with vocational skills, jobs, and other support, is advocated as a method to reduce recidivism rates.

You can find more information about the book on Kamala Harris’ website.

2 Comments

I was a person on the tail of doing life on the installment plan. What changed my course was a great wife and the desire to not go back, Being off of parole helped. It was like as long as I was on parole I kept my self recycling through the system. I gave up on trying to do right when I was on parole. It seemed to me that the deck was set against me. I'm not saying parole isn't necessary, but the length of parole is. I got away with being prosecuted for crimes in lieu of a parole violation. Whats the incentive? I was habitually addicted to drugs and knew that if I got caught committing a crime in SF all I would do at the most was a year with half time eligibility. No more than 8 months at worse. That's less time than if you are committed to the county.

This great comment, Anonymous, brings up the important question: what is parole supposed to do? Were parole an instrument of reentry, it would provide hope and opportunity.