Once upon a time, I was at a quantitative research conference, in which I was assigned to comment on a paper by two economist colleagues, Frank McIntyre and Shima Baradaran. They ran the numbers on bail, detention, and pretrial release, and found that, when controlling for severity of the offense and for criminal history, there was no racial discrimination in these pretrial decisions. The math was impeccable–far above my paygrade–because Frank and Shima are excellent at what they do. Their findings were deeply demoralizing: because race is so deeply baked into the American way of life, it turns out that people of color commit more of the kinds of offenses that land them in jail pretrial–either because of pretrial detention or because of bail amounts they can’t pay. It’s one of many examples in which well-intended efforts to scrub out race fail because of its protean quality: you hide it here, it pops up there. Yes, people of color do commit homicides and other violent crimes with more frequency than white people, and this happens for the same reason that they get more frequently arrested for the drug crimes they do not commit with more frequency: systemic racism. If we can’t address basic issues of deprivation, neglect, intergenerational poverty, and lack of opportunities for people of color and in low-income neighborhoods–crime will persist for the same reasons that criminalization persists.

This is the basic issue undergirding the debate about Prop. 25: In a world plagued by systemic classism and racism there are no good choices, but some are better than others. Prop. 25 invites us to affirm a reform adopted by the California legislature two years ago, which has not yet gone into effect: the elimination of cash bail. Lest you be confused, know that a “yes” vote affirms the reform and rejects cash bail; a “no” vote rejects the reform and keeps cash bail in place.

Under a cash bail system, the judge typically looks at a bail schedule–a “price list” that attaches monetary amounts to offenses based on a crude severity scale. The price listed for the offense with which you were charged is your bail amount. Since this is not the kind of money most people have available, there’s a workaround: the bail bonds industry. The defendant or their family pay the bail bondsman a nonrefundable amount, typically a tenth of the bail amount, and the bail bondsman essentially assumes the risk of absconding (“jumping bail”) or reoffending vis-á-vis the court. The existence of this industry negates any risk-based element that the cash bail system might have, because the person doesn’t actually bear the risk of their own pretrial behavior. Worse, as per this amazing exposé by my colleague Josh Page, the predatory bail bonds industry essentially feeds off the sacrifices and risks of women of color, who pay the premiums and co-sign the bonds. Even the amount owed to the bail bondsman is far more than many families can afford, which is why poor people who are at low risk of absconding or reoffending remain behind bars, as my colleagues Hank Fradella and Christine Scott-Hayward explain in their book Punishing Poverty.

The 2018 reform sought to replace this unfair system, which explicitly locks people up pretrial because they are poor, with a risk-based, no-cash model. The judge would use a risk-assessment tool to calculate the risk of absconding and reoffending and decide on release and limiting conditions accordingly.

Because cash bail is so atrocious, it is difficult to find a “no on 25” argument that isn’t equally atrocious (“people have a right to pay bail” takes the cake–I swear it’s in the voter brochure), but there is one that has superficial appeal: risk-assessment algorithms, even when they don’t explicitly factor in race, can factor in variables that closely correlate with race (including, for example, one’s arrest history) and thus exacerbate racially discriminatory outcomes. In other words, we are replacing the existing system with something that might be just as discriminatory, made worse by the facade of statistical/actuarial neutrality.

The problem with this seemingly appealing argument is that it completely misses the point of why race correlates with these race-neutral variables in the first place. My colleague Sandy Mayson has a fantastic paper, aptly titled “Bias In-Bias Out”, in which she explains:

[T]he source of racial inequality in risk assessment lies neither in the input data, nor in a particular algorithm, nor in algorithmic methodology. The deep problem is the nature of prediction itself. All prediction looks to the past to make guesses about future events. In a racially stratified world, any method of prediction will project the inequalities of the past into the future. This is as true of the subjective prediction that has long pervaded criminal justice as of the algorithmic tools now replacing it. What algorithmic risk assessment has done is reveal the inequality inherent in all prediction, forcing us to confront a much larger problem than the challenges of a new technology. Algorithms shed new light on an old problem.

Ultimately. . . redressing racial disparity in prediction will require more fundamental changes in the way the criminal justice system conceives of and responds to risk. [C]riminal law and policy should, first, more clearly delineate the risks that matter, and, second, acknowledge that some kinds of risk may be beyond our ability to measure without racial distortion—in which case they cannot justify state coercion. To the extent that we can reliably assess risk, on the other hand, criminal system actors should strive to respond to risk with support rather than restraint whenever possible. Counterintuitively, algorithmic risk assessment could be a valuable tool in a system that targets the risky for support.

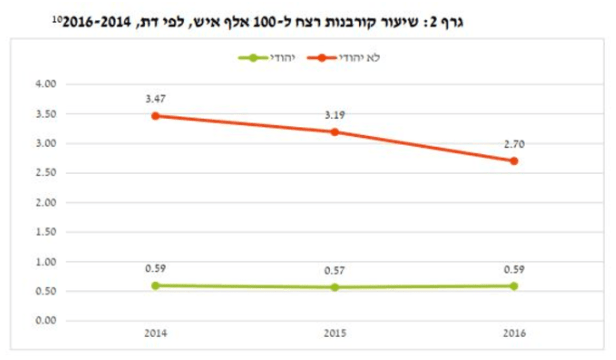

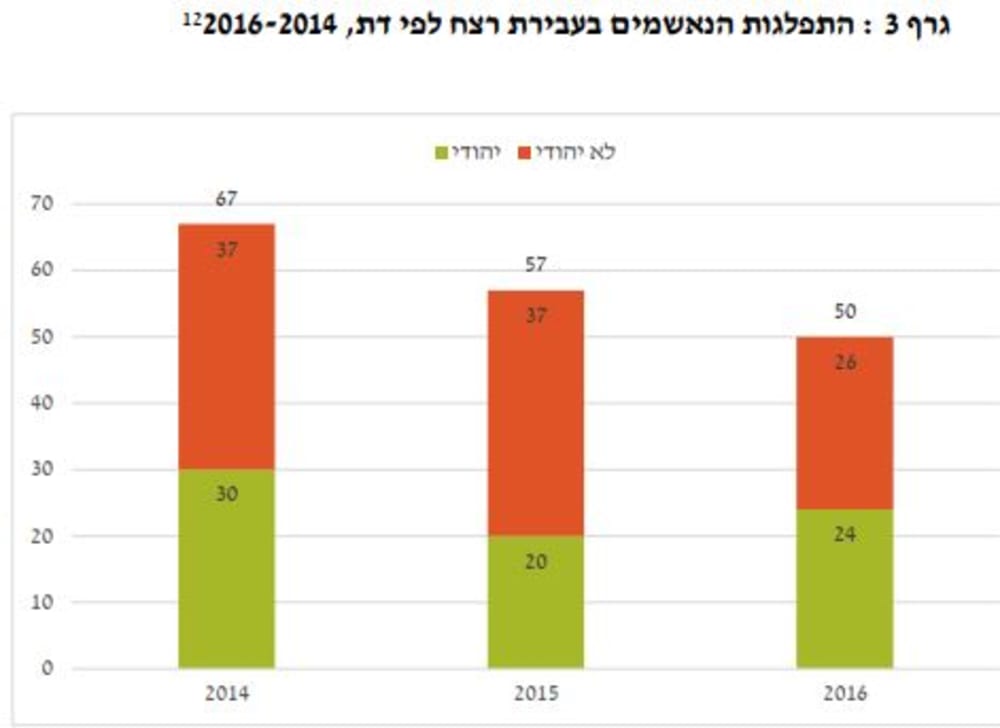

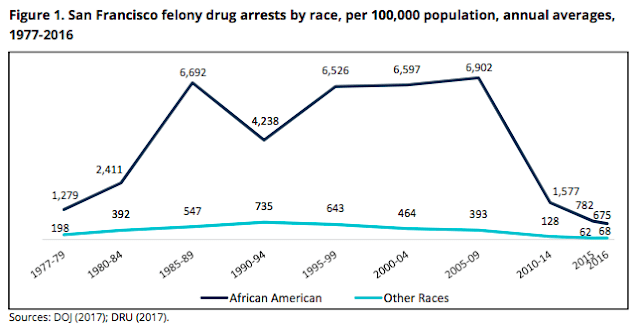

In other words, the algorithm is not “racist” in itself, and it can’t “scrub” racism out of the system. It reflects a racist reality in which, for a variety of systemic, sad, and infuriating reasons, people who are treated like second-class citizens in their own country commit more violent crime. In fact, the same problem is baked into Frank and Shima’s findings about the existing cash bail system: At the conference, our colleague W. David Ball, who was in the audience, astutely pointed out that the outcome was pretty much to be expected given the fact that, in California as in many other states, judges make pretrial release decisions on the basis of bail schedules–“price lists” that attach monetary amounts to offenses based on a crude severity scale. The overrepresentation of people of color in homicide offenses and other violent crime categories is an inconvenient truth for progressives–look at the report of the National Academy of Sciences on mass incarceration and at the evasive rhetorical maneuvers they use when they talk about this. Unfortunately, it is true, and as I explained above–the reasons why more African American people commit more homicides than white people are the same reasons why they are arrested more frequently for the drug offenses they don’t actually commit more than white people: deprivation, neglect, lack of opportunities, dehumanization and marginalization on a daily basis.

When you vote yes on 25, you are not exacerbating potentially racist outcomes from the algorithm. I can already tell you that the outcome will be racist, because it will reflect the reality, which is racist also. What you would do is eliminate the existing approach, which removes risk from the equation (because of the bail bondsman as the middleman) and lands people in jail simply because they cannot pay the bail amount. It won’t fix what is already wrong in the world, but it will take one slice of it–screwing people over because they are poor–and make it better. Vote Yes on 25.