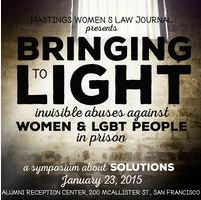

Today I attended the Hastings Women’s Law Journal symposium Bringing to Light: Invisible Abuses against Women and LGBT People in Prison. The symposium had three panels: reproduction, family, and specific issues concerning trans inmates.

The main theme that stood out for me was the question of choice and alternatives, and especially the inability to offer good alternatives in the context of a prison regime. Surely we can do better than the quality of health care that is offered to pregnant women, but that requires a lot of thought and working within difficult constraints. The first panel was held, of course, in the shadow of the horrifying discoveries about sterilizations in California prisons, and many of the panelists referenced that incident, as well as other horrors involving the management of pregnancy and birth in prison. The birth process itself and the immediate separation from the child are obvious problems. But what about, for example, the practice in Riverside of having pregnant women wear neon orange bracelets? The intent is probably good–to ensure that they are handled with extra care and safety–but what about a woman who wants to terminate her pregnancy and does not necessarily wish for the pregnancy to be common knowledge?

The same issue reverberated in the last panel, the one about trans inmates. The options for classification are fairly limited: a trans woman, for example, could be exposed to atrocious forms of abuse on the part of inmates and guards if placed in a men’s prison, but would also be ostracized in a women’s prison. And, as it turns out, different trans people have different preferences in this regard–some involving their safety and some involving their desire to form intimate relationship (which is very human and understandable and, in my opinion, deserving of the same amount of respect.) Isolation may protect one from some forms of abuse, but open other avenues of abuse, and has its own huge detriments. So what’s to be done?

Subjecting people to regimes of incarceration inherently robs them of a modicum of autonomy about their lives, and the choices are not abundant or good. Even when there are good intentions–and that is not always the case–they can be distorted by misunderstandings and generalizations. Advocating for special populations under these circumstances can be extremely fraught, and I’m very grateful to have learned more about this from the folks at the front line of advocacy.

No comment yet, add your voice below!