As I type this, thousands of Israeli Arab citizens, residents of Magd-al-Crum (an Arab town in the Upper Galilee) are protesting against the Israeli government’s failure to appropriately address violence in Israeli Arab society. Ha’aretz reports:

The day before yesterday two brothers were fatally shot at the town in a browl, and today another young man who was badly injured in the fight, Muhammad Saba, died of his injuries. The protesters are calling out derogatory calls about the police and its crime-fighting abilities, including, “Ardan [the police minister], you’re a coward”, and bearing signs saying, “violence–not in our streets” and “living in peace is already a dream.” Muhammad Baraka, the Chairman of the Supervision Committee for the Arab Population, said at the end of the march that, “if in Magd-al-Crum and [other] Arab towns there won’t be peace–there won’t be peace anywhere. It is not a threat, it is an elementary right for any citizen in a proper society.

Since the beginning of the year, more than 70 Arab Israeli citizens were murdered throughout the country. Among the marchers were thousands of villagers, as well as citizens from all over the country, mayors, Knesset members and religious leaders. Prominent at the rally were women, who wore black shirts for mourning, called out slogans and marched with their children who carried signs against violence. Even the family members of the two brothers who were murdered in the village, Halil and Ahmed Man’aa, attended the protest.

|

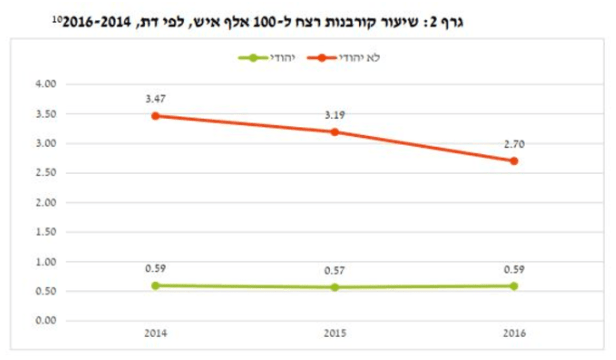

| Homicide victims per 100,000, by religion, 2014-2016 (non- Jews in red). |

The protesters in Magd-al-Crum are not taking a single incident out of proportion–they are responding to a devastating statistical reality. According to a new report from the Knesset’s Center for Research and Information, Israeli Arab citizens are disproportionately represented among homicide victims. Because homicide (like most violent crime) is primarily committed intraracially (this is true in the U.S. as well as in Israel), what this means is that homicide perpetrators are also primarily Arab Israelis.

|

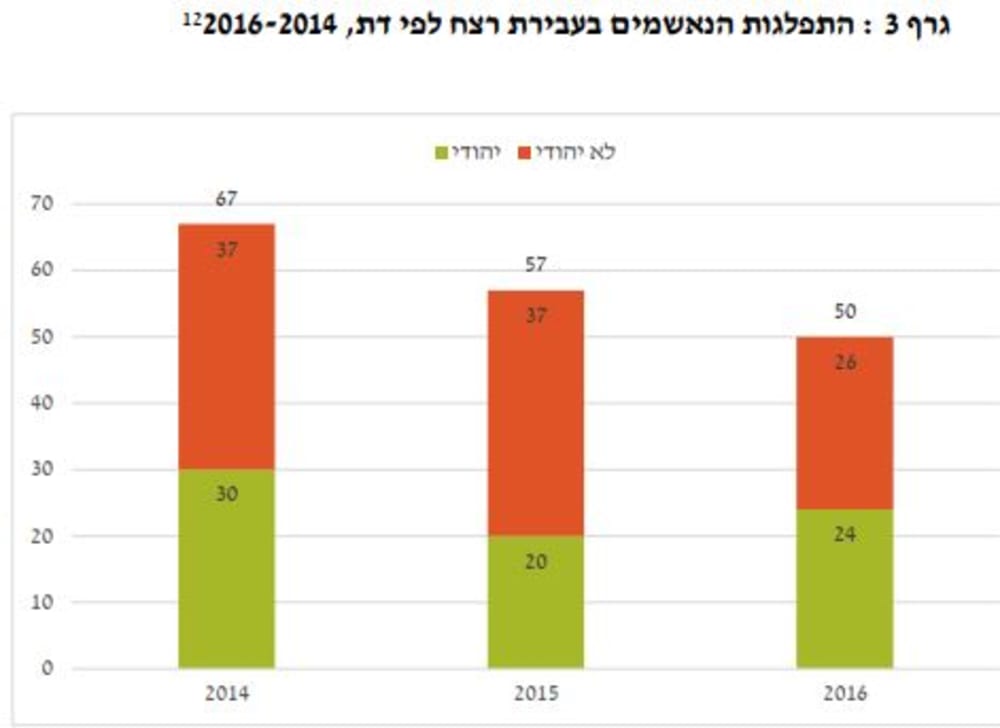

| Homicide defendants by religion, 2014-2016 (non-Jews in red). |

The graphs from the report prove the point. Arab Israelis, who constitute about 20% of the Israeli population, are responsible for more than 50% of homicide offenses per annum. This is not the fabricated, misleading product of overenforcement or targeting by Israeli police (many other things are, and we’ll get to it in a moment): it reflects actual bodies on the ground–dead people and the people who shoot them.

Just recently, after the Joint List of Arab parties won a record number of seats in the Knesset. After this electoral triumph, the party leader Ayman Odeh published a wonderful editorial in the New York Times–a testament to his very real qualities of leadership. Many commentators reflected on his blend of idealism and pragmatism and on his willingness to support Gantz as Prime Minister (against Netanyahu) but reluctance to join the government. But as a criminologist, I was more drawn to his important and knowledgeable commentary on the problems that really plague the Israeli Arab population:

Our demands for a shared, more equal future are clear: We seek resources to address violent crime plaguing Arab cities and towns, housing and planning laws that afford people in Arab municipalities the same rights as their Jewish neighbors and greater access for people in Arab municipalities to hospitals. We demand raising pensions for all in Israel so that our elders can live with dignity, and creating and funding a plan to prevent violence against women.

We seek the legal incorporation of unrecognized — mostly Palestinian Arab — villages and towns that don’t have access to electricity or water. And we insist on resuming direct negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians to reach a peace treaty that ends the occupation and establishes an independent Palestinian state on the basis of the 1967 borders. We call for repealing the nation-state law that declared me, my family and one-fifth of the population to be second-class citizens. It is because over the decades candidates for prime minister have refused to support an agenda for equality that no Arab or Arab-Jewish party has recommended a prime minister since 1992.

What might these resources include? I worry that the facile right-wing and left-wing solutions to Arab-Israeli violence are equally doomed to fail. Let’s start with the left wing. About a year ago I sat in a hotel lobby at the ASC annual meeting and talked to a respected and experienced Israeli criminologist, who told me of his Israeli colleagues’ reluctance to openly discuss Arab crime rates. It’s bad form among left-wing intellectuals to admit that a population that suffers (truly) from overpolicing, overcriminalization, and harsh sentencing, might also be responsible for actual crime on the ground.

This, of course, reminded me of James Forman’s Locking Up Our Own. One of the great strengths of the book is that, by contrast to Michelle Alexander and others to whom racial discrimination seemd to be wholly a product of racist policing, racial profiling, and the war on drugs (note that even Michelle Alexander eventually came around to rejecting this facile explanation, albeit without admitting her own errors), Forman’s protagonists, black politicians and police chiefs, sought what they thought in good faith to be the best for their communities. Why would Burtell Jefferson embrace stop and frisk? Why would black politicians embrace marijuana enforcement and lax gun laws? Because they were attentive to a community that was really–not just in the putrid minds of white supremacists–ravaged with violence. Perpetrated against black people by black people.

What is often lost in the chatter of those who deem the question “what about black-on-black crime?” racist is the deep understanding that the vast majority of the African American population does NOT commit crime, and that these politicians and cops were operating on behalf of their communities, rather than against them. It could even be argued that this oversight, in itself, is a form of racism. But I see this evasion, the fudging of this truth, everywhere. As a shining example of this, take a look at the NAP commission report on the causes of mass incarceration and how it talks about race and violent crimes:

No comment yet, add your voice below!