| A Jewish folk story I know goes like this: A farmer lives in a house with his wife and children and the grandparents, and it is so noisy that he thinks he will go crazy. He goes to the Rabbi for advice. The Rabbi says, “bring your goat into the house.” The farmer says, “but that’ll just make everything worse!” The Rabbi says, “do as I say.” The farmer, skeptical but trusting the Rabbi’s wisdom, brings the goat in. A week later, the man returns to the Rabbi, who asks him, “how’s it going?” The man says, “it’s so much worse! We are so crowded and the goat is pooping everywhere and eating our food!” The Rabbi nods and says, “now, take the goat out of the house.” Upon hearing that the beach closures will only cover Orange County–the specific beaches where overcrowding and noncompliance were visible on the weekend–I felt very relieved and happy despite not having actually gained or lost anything. It occurs to me that this is a great illustration of Kahneman and Tversky’s work on the entitlement effect. The entire emotional rollercoaster was a fascinating study in comparisons and tribalism. When we were threatened with the closures, I felt anger toward local government (“how can they take this away from my child?!”), at the Orange County beachgoers (“this is why we can’t have nice things!”) at friends who disagreed with me; in short, at “others”, a-la Sartre’s “Hell is other people.” Our powerful teacher, COVID-19, has given us plenty of opportunity to develop and espouse strong opinions about other people: how they are handling the pandemic, how their situation compares to ours… in other words, a lot of dividing the world into “us” and “them.” Kanheman and Tversky’s work is so helpful for understanding the formation of these aggressively negative opinions. Cognitive bias conditions us to notice and retain evidence that’s consistent with our views. And we tend to not notice or reject evidence that doesn’t support our views (e.g., we are disgusted with one racist post, deduce that “Nextdoor is full of racists,” and ignore the dozens of kind, helpful posts.) Attribution error makes us explain people’s behavior in different ways based on whether or not we like them: If it is an enemy of ours, and they do something good, then we attribute it to circumstances, the situation. When they do bad things, we attribute their behavior to their disposition. With friends, it is the other way around (e.g., a friend is well prepared and provides for their family by shopping extensively; a stranger, or someone I dislike, is a selfish hoarder.) Harvard ethicist Herbert Kelman writes: “Attribution mechanisms . . . promote confirmation of the original enemy image. Hostile actions by the enemy are attributed dispositionally, and thus provide further evidence of the enemy’s inherently aggressive, implacable character. Conciliatory actions are explained away as reactions to situational forces—as tactical maneuvers, responses to external pressure, or temporary adjustments to a position of weakness—and therefore require no revision of the original image.” Theologist Robert Wright, who has looked at the connection of Buddhism and modern psychology, observes that a big part of the formation of essence involves feelings. There is a lot of evidence now in psychology that when we look at any person, we react to some extent at the level of feeling, and then that shapes the way we behave towards that person With people, feeling is so critical to perception that the very identification of people depends on feelings in ways more subtle than we are normally aware of. Feelings are at the core of the comparing mind. Leon Festinger posits that we compare ourselves to people we perceive to be worse than we are (less moral, less good, less worthy) to increase our self esteem. Much of the debate over compliance and social distancing policy divides people into camps: Who has it easier? People with kids? People sheltering alone without kids? People sheltering with someone they don’t get along with? Does the age of the kids matter? If your comparing mind is in overdrive–mine sure has been, and I’m seeing a lot of evidence around me that it’s not just me–start by having some compassion for yourself. Comparing is part of the human experience. Second, the inchoate fear and anger in your mind will invariably look to hook onto something concrete. It may or may not be a righteous coat hanger. But it is a coat hanger, and we have to see it in order to sit with it. How to address the comparing mind: Byron Katie’s work, which I have a complicated reaction to, involves examining limiting thoughts. You can use her Judge Thy Neighbor worksheet to examine rigidly held opinions about others. Using practices of self compassion and compassion for others, such as Krisin Neff’s exercises, can also be very helpful, as can this wonderful exercise from Rick Hanson called “drop your case.” In general, anything that frees your mind from a zero-sum-game is going to be a healthy way to look at things. Resources may be finite, but joy and kindness are not (and neither is suffering)–so focus on that. |

Nama Shoyu Ginger Sauce (and lovely salad)

When we were in Cambridge, MA, in the fall, one of our favorite places to eat was a joyous hippie joint on Massachusettes Avenue called Life Alive. I loved everything they served–the thoughtfully planned bowls, their amazing miso soup with mushrooms, and their excellent juices and smoothies. What made everything better was that they slathered several of their dishes with an unbelievably tasty sauce. One of my major projects was to try and recreate that sauce in my own kitchen. Thankfully, many people are obsessed with this sauce, and one intrepid food blogger, SarahFit, has the winning formula, so–mission accomplished! Sarah, you have my eternal gratitude. Here it goes:

The salad above consists simply of brown rice noodles (I like this kind, which I ordered in bulk for our household), tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, scallions, cilantro, parsley, and edamame. Cook noodles, rinse with cold water, mix with the vegetables (sliced or shredded to your liking), and slather with a generous amount of the magical sauce.

You can put this sauce on anything: it brightens bowls, asian fusion dishes, roasted vegetables, and even tofu scrambles. Go ahead and double (or quadruple) the recipe. You’re welcome.

Closing State Beaches and the Problem of Noncompliance

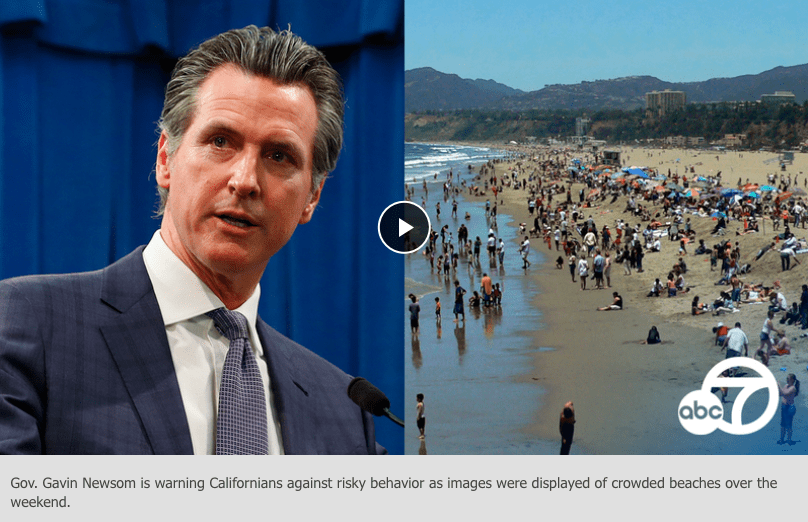

When I heard late last night of Gov. Newsom’s decision to close California beaches because of crowds, I was devastated. I observed my thought pattern immediately cycle through the first three of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief: denial (“I can’t believe this. It can’t be happening. Surely this won’t happen”), anger (at the Governor, at the mayor, at the lawmakers, at the folks congregating in five SoCal beaches – “you are why we can’t have nice things!”) and depression (“what am I going to do? How will we get through this month?”). This morning I progressed to the bargaining stage (“wait, he said state beaches, right? So SF beaches, which are run by the city, are exempt, right?”) and I might find some acceptance later this afternoon.

In short, my inchoate fear, sadness, and uncertainty, finally found an appropriate coathanger to hook itself to, and I was in emotional turmoil throughout the night.

Now that the emotional storm has passed, I’m thinking a bit about what park and beach closure policies have to teach us about the punitive and cooperative aspects of making public policy. Oftentimes when prohibitive legislation is considered on any topic, ranging from speed laws to tax policy, people forget that any policy brings with it some level of noncompliance. A classic article by Fred Coombs provides a typology of reasons for noncompliance: “(1) lapses or ambiguities in communication; (2) insufficient resources; (3) an objection to the policy itself (i.e., its goals or its assumptions); (4) distaste for the action required; or (5) doubts about the authority upon which the policy is based, or that authority’s agents.”

Looking particularly at (3) and (4), which are different facets of how much one agrees with the policy decision and how much one is inconvenienced by them, reminded me of Tom Tyler’s classic work Why People Obey the Law. Moving away from the “instrumental” explanations (“people obey if there’s something in it for them”), Tyler focuses on normative ones, which are concerned with–

the influence of what people regard as just and moral as opposed to what is in their self-interest. It also examines the connection between normative commitment to legal authorities and law-abiding behavior.

Tom Tyler, Why People Obey the Law, pp. 3-4

If people view compliance with the law as appropriate because of their attitudes about how they should behave, they will voluntarily assume the obligation to follow legal rules. They will feel personally committed to obeying the law,

irrespective of whether they risk punishment for breaking the law. This normative commitment can involve personal morality or legitimacy. Normative commitment through personal morality means obeying a law because one feels the law is just; normative commitment through legitimacy means obeying a law because one feels that the authority enforcing the law has the right to dictate behavior.

According to a normative perspective, people who respond to the moral appropriateness of different laws may (for example) use drugs or engage in illegal sexual practices, feeling that these crimes are not immoral, but at the same time will refrain from stealing. Similarly, if they regard legal authorities as more legitimate, they are less likely to break any laws, for they will believe that they ought to follow all of them, regardless of the potential for punishment. On the other hand, people who make instrumental decisions about complying with various laws will have their degree of compliance dictated by their estimate of the likelihood that they will be punished if they do not comply. They may exceed the speed limit, thinking that the likelihood of being caught for speeding is low, but not rob a bank, thinking that the likelihood of being caught is higher.

Tyler thinks that that fostering compliance from a normative place works better because it requires less enforcement and it fosters more care for people’s values and motivations. He coins the concept “procedural justice” to argue that, when people think a decision has been made fairly–even if it disadvantages them personally–and they have been treated respectfully, they are more likely to comply.

It is inevitable that not all citizens will share the same normative values or the same level of legitimacy in government. While most of us understand the need for extreme social distancing measures to save lives, some of us simply do not believe the facts the government cites as a basis for its decisions. We might think the government is ignorant, or we might think it is deliberately misleading us because of ulterior motives. We might think the government has good intentions, but is missing the mark with the policies. Or, we might simply find the new requirements unbearable.

Looking at my own reaction to the order, it was guided by similar questions. Is it true that there’s noncompliance? Yes, we have evidence of it in SoCal. Is it widespread? No, by the Governor’s own admission: “About 100 beaches, easily defined 100 beaches, and there were five where we had some particular challenges. Overwhelming majority there were no major issues. Quite frankly no issues,” he said. Is the reaction disproportionate to the threat? That’s a matter of perspective. Look at these concerns from local government officials:

California State Assemblymember Melissa Melendez fired back at Newsom’s decision on Twitter, stating “This is not going to end well. Californians are not children you can ground when they don’t ‘behave’ the way you want.”

Orange County Board of Supervisors member Donald Wagner on Wednesday acknowledged the governor’s ability to close the county’s beaches, but said “it is not wise to do so.”

“Medical professionals tell us the importance of fresh air and sunlight in fighting infectious diseases, including mental health benefits,” Wagner wrote.

“Moreover, Orange County citizens have been cooperative with California state and county restrictions thus far. I fear that this overreaction from the state will undermine that cooperative attitude and our collective efforts to fight the disease, based on the best available medical information.”

All the noncompliance factors are there: an emotional insult at not being respected enough to follow the rules out of our own volition, doubts about the values behind the approach (punitivism vs. fresh air), concerns that suppressing people too much will backfire and yield more noncompliance. Right out of the Coombs and Tyler playbooks.

The big question is: What, ultimately, will produce more compliance? Do we get more cooperation if we relax the order, counting on people’s common sense (and accepting that some will not display such common sense), or if we impose the order, counting on people’s agreement in principle? My gut tells me that, in the short term, enforcement stuff might be better, but in the long term, people’s sense of legitimacy and compliance will wear off, and we might see worse behaviors all across the state than the ones we saw on the beach. The problem is that levels of compliance are very tricky to model. They depend on demographics, political views, and other factors, which are changing daily, and would make this very difficult to predict even for compliance experts.

Ultimately, I think my personal reaction to this has been a great teacher. It opened some unexpected compassion gates: I managed to find within my soul more than a modicum of empathy for the feelings of Huntington Beach protesters, Spring Break revelers, and anti-vax conspiracy theorists. Don’t get me wrong: I have deep ideological disagreements with all these three groups and a much higher belief in the legitimacy of our local government (let’s talk about Trump some other day, shall we?). But what we share is the deep sense of emotional injury by a curtailment of a freedom we treasure. That’s something I can understand and sit with emotionally even as I ideologically disagree. In our case, my family treasures nature and water, and my son thrives during these difficult times because he has the world’s biggest sensory box to play and learn in. I very much hope our local government will not take this away from him.

Beyond Beef Meatballs in Tomato Sauce

When I became vegan, mind-bending meat substitutes like Beyond Meat did not exist. During my fellowship at Harvard’s Animal Law & Policy Program last fall I was amazed to attend talks by leaders in the plant-based meat substitute industry–we’re in for a world in which, should we choose wisely, we can minimize an enormous amount of suffering.

I did like meatballs quite a bit as a kid, so having the option to enjoy them cruelty-free has been a real boon. You can buy the formed burgers (they sell them in boxes of two) but a much more economic option is to get the ground beef package. With a little bit of kitchen magic, this transforms into something that transports you to childhood.

Ingredients

For the meatballs:

- 1 package Beyond Beef

- 1 slice of bread (whole wheat or sourdough, something sturdy, works best, but don’t sweat it if you have something else)

- 1/3 large onion, minced

- 1 large handful of fresh parsley

- 1/2 tsp cumin

- 1 tsp tomato paste (optional)

- a little bit of salt and pepper

- enough olive oil to coat the bottom of a large pan

For the sauce:

- 6-7 tomatoes, thinly sliced (this calls for truly wonderful tomatoes, because it’s a very simple sauce without seasoning.)

- 1 tsp olive oil

- THAT’S IT!

First, make the sauce. Heat the olive oil in the pan and add all the tomatoes. When they start sweating, lower the heat and cook on low heat until the sauce reduces somewhat.

Toast the slice of bread until deeply browned, then soak in water for a few minutes. Wring water out of the bread and tear it into a few pieces. Place the toasted, wet bread pieces in a food processor with all the ingredients except the olive oil and pulse until mixed and sticky (it can stay a bit chunky.)

Heat up olive oil in a pan. With damp hands, form 1/5” diameter balls, flatten them a bit. Place them in the hot pan and fry until the bottom is golden (about 2-3 mins), then flip over to the other side (the newer ones will be done faster because of the pan temperature.)

As soon as you finish frying the meatballs, drop them into the tomato sauce in the other pan and cook for a few minutes.

You can eat this over mashed potatoes or pasta, or put this in a meatball sandwich. And you can substitute more complex tomato sauces if you desire.

Ramen Primavera

In the early days of shelter-in-place, our trusty vegetable providers had to reorganize their route to accommodate the unreasonable volume of orders. As a consequence, I had to rely on frozen veg and pantry items quite a bit, but I did have some brussels sprouts! This is how the Ramen Primavera, which fed us and some neighbors via socially-distant doorstep delivery, was born. You can obviously improvise with whatever you have at home.

Ingredients

- 1 tsp olive oil

- 1 lb brussels sprouts

- 1 bag frozen corn

- 1 bag frozen peas

- 1/2 onion

- 1-2 cloves garlic

- 1 tsp onion powder

- 3 tbsp soy sauce

- 2 tbsp nutritional yeast

- 1/3 cup water

- 1 package ramen noodles (I like this fancy kind or this green kind with Moroheiya.)

preparation

Heat up the olive oil in a wok. Slice brussels sprouts into quarters lengthwise and throw in. Sauté for five minutes. While you do, mince the onion and garlic and add them. Then, add the spices (onion powder, soy sauce, yeast) and the water. When the water starts bubbling, add the frozen veg. Cook for about 10-15 mins, or until the brussels sprouts are soft but not mushy. In a separate pot, cook the ramen noodles in water according to instructions. Strain. Add the cooked noodles to the veg mix and toss around to coat with the dressing.

Pandemic Passover: Our Virtual Seder Table

The Torah spoke of four sons: one wise, one wicked, one simple, and one who does not know how to ask. Each of these sons calls for a different approach in the telling of the Exodus story. This year, as I made preparations for co-hosting (with my colleague and friend Dorit Reiss) our first-ever Zoom seder for dozens of participants, I wondered which son I was.

The wise son would deeply ponder the minutiae and symbolism of the Passover rituals. As the wise son, I reflected on the meaning of a holiday about overcoming slavery, rediscovering freedom, a rather hefty dosage of retribution, and delaying gratification, amidst the shelter-in-place order. The holiday took on a new meaning, as my definitions of slavery, freedom, and the promised land have been shaped by current events. Mostly, I have been thinking about the meaning of freedom in the context of prisons and COVID-19 health risks within them, and recommitting to the fight to save as many people as possible, both behind bars and on the outside.

The wicked son excludes himself from the celebration. I don’t see this as “wicked,” necessarily, but rather as the comparing mind. “Sure, you celebrate all you want; you don’t have little kids;” “Sure, you have it easy, your kids are small, mine have to do homework.” “Sure, knock yourself out and watch Netflix, child-free person.” “Sure, enjoy your family happiness while I rot here in solitude.” The comparing mind alienates and isolates us from our friends and neighbors. Let’s drop all that and remember that there is no “other.”

The simple son asks, “what’s this all about?” I had to go back to basics in creating a virtual PowerPoint haggadah for us to use during the ceremony–remembering old passages, enjoying the familiar turns-of-phrase even before engaging with the deeper meanings.

The son who does not know what to ask is silent. But in my case, the silence was an industrious one and full of preparations.

What’s on our happy Oaxaca-inspired seder plate? Celery, hot sauce pickles (in lieu of horseradish), haroset balls (combining any dried fruit and nuts at home with a grated apple in a food processor and making balls, then rolling them in coconut), and the classic tofu eggless salad in lieu of the egg. And the orange, you ask? Here’s the story. As we’ve been co-leading the Seder as two women for about twenty years–Dorit emceeing and I putting together the music–I think an orange more than belongs on our seder plate!

Muttar Tofuneer

We are so lucky during this pandemic to get fresh vegetables every week from our local organic CSA Albert & Eve. A big box comes in without fail every Tuesday. But since they are flooded with larger-than-usual deliveries to existing an new clientele, the box doesn’t arrive at the crack of dawn as it used to. This means that, after a week of vegetable Tetris, I’m sometimes left without fresh produce for a meal or two.

But fear not, because we have lots of fantastic Indian spices, as well as Vegan Richa‘s legendary cookbook. We have found the book incredibly useful, and today I was especially thrilled with it, as I had a bag of frozen peas and a block of my favorite tofu, Hodo Soy. Because the paneer is very delicate and the tofu very tolerant, I changed the cooking instructions somewhat to allow it to soak more of the curry sauce. I added a pinch of nutritional yeast to up the “paneerish” flavor profile. We also omitted the spice, because Rio dislikes spicy foods (we’ll convert him yet, but he’s still a toddler!) The original recipe calls for spinach and for Richa’s very special almond paneer (a lot of work but worth it), but I decided to use the fantastic sauce for peas and tofu and we happily enjoyed it over rice. It’s very easy!

Ingredients

- 1 minced onion

- 2 tsp coriander seeds

- 1/2 tsp cinnamon

- 1-2 cloves

- 1/2 tsp cumin seeds

- 1 tsp ground ginger

- 1 tbsp minced garlic

- 1.5 cup canned tomatoes

- 1/2 cup water

- 1 bag frozen peas

- 1 block extra-firm tofu, cubed

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast

- 1 tbsp vegan yogurt

- 1/2 cup unsweetened plant milk

- 1 tsp apple cider vinegar

Preparation

Heat up wok. Dry-roast coriander and cumin. When wok is hot, add the onion and sauté until fragrant. Remove from heat and place in a blender with the rest of the spices, the water, and the canned tomatoes. Blend until creamy. Pour back into wok and turn on the heat. Add peas, yeast, and cubed tofu. Cook for 12-15 minutes. When it reduces and thickens, add yogurt, plant milk, and apple cider vinegar. Cook for another five minutes. Serve over rice.

The “What’s In It For Me?” Angle on COVID-19 Prison Releases

The thing everyone was warning you about has happened: the prisons, incubators of COVID-19, are spreading it to the general population. The Columbus Dispatch, reporting on the Ohio prisons rife with infections and disease, reports:

Marion County’s top health official is urging vigilance as the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in a Marion prison spills into the community.

More than 80% of Marion Correctional Institution’s inmates have tested positive for the coronavirus, as have more than 160 corrections officers and other employees, according to the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction. Those workers live in Marion County and surrounding counties.

More prisoners might have the virus because although a prison spokesperson previously said that mass testing was completed more than a week ago, spokesperson JoEllen Smith said Friday that only 2,300 tests had been administered. She did not clarify whether that included employees, and the prison has about 2,500 inmates.

Even excluding the prisoners who have tested positive, Marion County has a higher number of cases per capita than almost every other county in Ohio, including densely populated ones such as Franklin and Cuyahoga, according to Ohio Department of Health data.

[Health commissioner Traci] Kinsler attributed Marion County’s high number of cases per capita to the prison outbreak.

The idea of prisons as incubators of miasma is as old as the prison reforms of John Howard. Ashley Rubin has a terrific thread on this on Twitter. As she explains, preventing the spread of disease was at the forefront of the reformers’ interests, and for many thinkers was a metaphor for the spread of crime.

Many of the campaigns for releasing prisoners that I’ve seen make the scientifically correct point that, as long as U.S. prisons remain Petri dishes for the virus, nobody’s safe. I want to draw an important distinction between this argument and the equally correct argument that prisoners–better said, people who happen to be in prison during this outbreak–are human beings, too, whose protection from the virus would have to be a priority from a human rights perspective whether or not they endangered others.

I’m wondering whether the former argument is made not only because it is sound (it is) but because of realpolitik. In Cheap on Crime I argued that the post-recession reforms a-la “justice reinvestment”, which led to a decline in the overall U.S. prison population for the first time in 37 years, benefitted from having a morally neutral cost argument, which allowed activists and advocates to break the decades-long impasse between public safety and human rights. It’s quite possible that framing prisoner release as a “what’s in it for me?” argument, rather than an argument on behalf of the prisoners themselves, has more persuasive power, and if so, I’m all for whichever argument gets less people, in and out of prison, sick or dead.

But just so that we get a glimpse of life behind bars, here are some words from Kevin Cooper, an innocent person on San Quentin’s death row (shared with me via email through Innocence Project):

Experiencing COVID-19 on Death Row

By Kevin Cooper

In my humble opinion being on death row with this COVID-19 pandemic raging is like having another death sentence. I can and do only speak for myself in this essay, and I must admit that I am scared of this virus!

I pride myself on not being scared of anything or anyone on death row, not even death itself, because after all this is death row. But this virus is more than just dying, or death. It’s a torturous death, like lethal injection is.

I do all I can to take care of me in here under these traumatic times and stressful circumstances. I social distance, I wash my hands regularly, clean this cage that I am forced to live in on a regular basis, and I often ask myself is this enough?

Every inmate who lives next to me or around me to my knowledge is taking care of themselves too. Quite a few still go outside to the yard every other day as we are allowed to do. I went out for the first time two days ago after a month living non-stop inside this cage. I went out to get fresh air.

This unit, East Block, has staff who have been giving us cleaning supplies such as “cell block” which is a strong liquid cleaning agent, and we use that to spray on a towel and wipe the telephone down before each inmate uses the phone. We have been given hand sanitizer for the first time since this pandemic started. It’s a 6-ounce bottle and the writing on it says World Health Organization Formula. The same World Health Organization that Trump just stopped funding…no joke!

We still have not received any mask* though a memo was sent around last week stating that cloth masks were being made to be passed out to inmates but that they have not yet been finished being made. Who is making them? I don’t know.

We people, we human beings on death row aren’t for the most part cared about by society as a whole. That truth makes some of us wonder, including me, do the powers that be truly give a damn whether we human beings who have been sentenced to death by society care if any of us get the coronavirus and die from it in a tortuous way?

In 2004 I came within 3 hours and 42 minutes of being tortured and murdered/executed by the state of California. I survived that, and have worked very hard with lots of great people to prove that I am innocent, that I was framed by the police and that I am wrongfully convicted. To do all of this and, especially to survive that inhumane and manmade ritual of death in 2004, only to be taken out by COVID-19 is something that honestly goes through my mind on a regular basis. Right now, I am free of this virus and I am doing everything to stay this way. But that thought, that real life and death thought of the coronavirus taking my life is always present, especially under these inhumane manmade prison conditions on Death Row.

*On Monday, April 20th, Kevin called to say: I received a cloth face mask today as did everyone here on death row. We are now instructed to use it every time we leave the cell.

Self-Compassion

Parenting Without a Village

Roberto Benigni’s wonderful film Life Is Beautiful tells the story of a father who, sent to a concentration camp with his young son, creates the illusion of a “game” at the camp to shepherd his son unscathed through the horrors of the Holocaust.

I’ve been channeling the spirit of Benigni’s character in the last six weeks all day, every day, and we’re now told there’s going to be another month of this. The continuing effort to be everything for my son, to foster happy, meaningful experiences for him, to make this time special, and to do what I can to minimize the trauma he might experience as a consequence of social isolation at a tender, formative age, is the main and most important project of this time for me–possibly the most important project of my life. It is deeply fulfilling, full of joyous moments, and–yes–deeply exhausting and depleting at the same time.

The other day I was on a work call (Microsoft Teams), in which I had to explain to our dean that fronting as ideal workers on these calls echoes our fronting as ideal parents at home and is truly impossible, and that our ability to participate in the sacrifices that the situation demands–teaching nights and weekends–was not an option unless the preschools and daycares opened. A well-meaning colleague who is child-free shared with us a link to an app that silences background and child noises on work calls.

While this was kindly meant, the distortion embedded in it was colossal. I don’t want or need an app to silence my child. I need my work to recognize that my child needs me and that he is at the top of my priority list. I need to hear my child MORE, not less, during this time. The capitalist workplace would frame our family as an inconvenience to the enterprise, but it is the enterprise–the long workday, the expectations of splitting an organic life–that is the real inconvenience.

We are mourning the paid day-long structures that keep our children busy and social while we engage in the socially approved tasks of the adult working world. And of course, this virus, which is a great teacher, has exposed financial inequalities and problems in the provision of this service. But this hides from sight the ways in which this service in itself is a distortion.

In The Wild Edge of Sorrow, writing about trauma caused by family, Francis Weller observes:

Having worked with people for more than thirty years in my practice, it is clear to me that finding a target to blame is effortless. Nothing is asked of us when we simply assign fault to someone else for the suffering we are experiencing. Psychology has colluded in the blame game, pointing an accusing finger at our parents. While many of us suffered mightily because of unconscious parenting, we must remember that our parents were participants in a society that failed to offer them what they needed in order to become solid individuals and good parents. They needed a village around them—and so did we. Of course we were disappointed with our parents. We expected forty pairs of eyes greeting us in the morning, and all we got was one or two pairs looking back at us. We needed the full range of masculine and feminine expressions to surround us and grant us a knowledge of how these potencies move in the world. We needed to have many hands holding us and offering us the attention that one beleaguered human being could not possibly offer consistently. It is to our deep grief that the village did not appear.

For those of us living the life of professionals–mobile, class-jumping, geographically removed from our families for opportunities–this crisis brings up the deep grief not only over the loss of this village, but also the loss of its paid replacement. It makes me wonder about Pa and Ma in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s first book, Little House in the Big Woods (and apparently I’m not the only one.) How did Pa and Ma cope without their village? Without their extra pairs of eyes and hands? What was their internal world, as parents? Was there exhaustion? Was there mourning for community? Was there worry about the girls’ socialization? Or were their emotions shaped by an upbringing with different expectations?

Intellectualizing this feeling of grief or venting about it seems as alienated from the experience as ignoring or suppressing it. There are countless moments of grief and exhaustion and fear, as there are countless moments of elation and joy and overflowing love. Sitting with them and feeling them is important, because these moments are what is happening now. Sitting with the grief as it wells. Sitting with the joy as it erupts. Not just in formal practice. Moment to moment, throughout this rich and strange moment in our lives.