A couple of weeks ago I posted about the comparing mind and how to soften our judgment of others. The pull toward judgment is so strong–I’m encountering it in myself as well as in lots of people around me who are ordinarily kind and patient–so I find myself posting about judgments again. During today’s outing with my son I was mindful of how a six-foot measuring stick has been embedded in my brain, and that was the first thing I noticed about people around me–that and whether they were wearing masks. It was as if something inside me yearned to control and chide other people’s behavior. The act of perceiving others’ compliance was so instantaneous that it frightened me. Being cognizant of this feeling, and sensing the “hook” of the temptation to judge in myself, has given me more understanding of the judging behavior of others.

On our outing, we traveled 2.23 miles to honor the memory of Ahmaud Arbery, the young man who was so cruelly murdered a few months ago while going on his daily run. Two suspects–a father and son–have now been charged with his murder. We will learn more during the trial, but the chilling footage suggests that Ahmaud was gunned down for no other reason than the color of his skin–yet another horrifying tragedy building on our racist legacies.

As we were walking, I was thinking about the horrors of these immediate judgments and biases. Before our pandemic times, we would look at passers-by in the streets and our unconscious would sort them into groups based on their gender expression, ethnic or racial appearance, or the apparent quality and fit of their clothes. These and other factors determine not only how we see people, but sometimes whether we see them at all. China Miéville’s wonderful novel The City and The City is set in two European city-states occupying the same physical space, but without mutual diplomatic relations. The citizens of each city are socialized, since infancy, not to see the buildings, cars, and people of the other city. When the hero has to investigate a disappearance from one city to the other, he has to undergo training to “unsee” his own city and “see” the other.

This week, UC Hastings and other businesses and people in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco sued the City of San Francisco for its neglect to address the overwhelming crisis of homelessness, drug dealing and mental disability that has characterized the Tenderloin, especially since the pandemic. I’ve spoken about this with students who live in our dorm, the Tower; even though we all have witnessed the immense suffering in the streets surrounding campus for years, the virus and resulting crises have magnified the suffering, to a level that affects everyone in the Tenderloin–housed and unhoused alike. We think of ourselves as good, kind, compassionate people, and yet we must harden our hearts and “unsee” the human suffering at our doorstep; it has finally risen to a level of tragedy that can no longer be unseen.

These snap judgments we make are at the heart of the many mundane ways in which we treat others badly. Most of us (I believe and hope) do not share the murderous intents of the people who accosted and shot Ahmaud. But how many people who think of themselves as kind and compassionate perceive people who do not look like them as dangerous, threatening, unpleasant to interact with, and move to the opposite sidewalk?

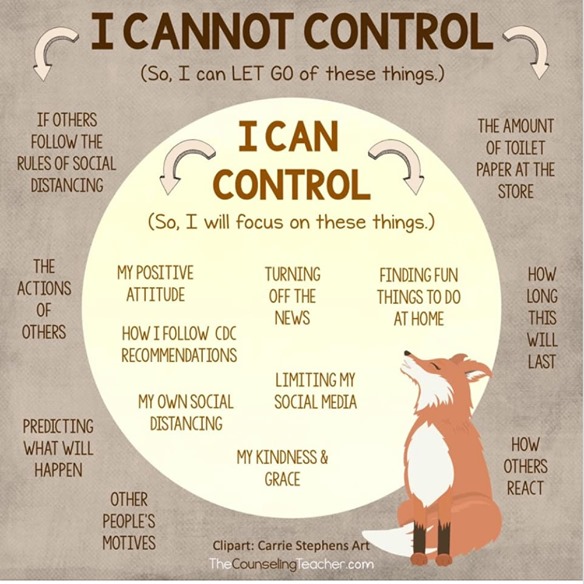

With the current threat at our doors, the usual features that our biased minds would glom to, to offer a snap judgment of the person walking toward us–poor, dangerous, friendly, you name it–have receded to the background, and our immediate biases have clung to masks and distances. The first thing we see now goes beyond poor/rich, male/female, white/nonwhite. It goes to masked/unmasked and distancing/not distancing. And so, our judging energy has gone there, where it might have gone elsewhere in past times when we noticed other things. It has been a profound education for me in the nature of instant visible biases.

I imagine some people reading this will be rightfully upset about the comparison between racist murderers and people who just want others to participate in the measures we are taking to prevent contagion. Of course motivation matters. But look at what the presumably commendable effort to shelter in place is making people do: scream at other people, slash each other’s tires, write horrible notes to each other, place rotten meat at people’s entrances as punishment for their perceived violations. For people imbued with a commendable motive, these are not particularly commendable (or effective) actions.

We must heal and fix the world, so that young people’s promising lives will not be cut short by race-fueled hatred, and so that poor and suffering people will not be ignored and unseen. Let’s start by sitting with our own judging minds, let go of others’ behavior that we cannot control, and then find the space to unite in active hope to work for racial and economic equality. The revolution is bigger than all of us, but it starts inside us.

No comment yet, add your voice below!