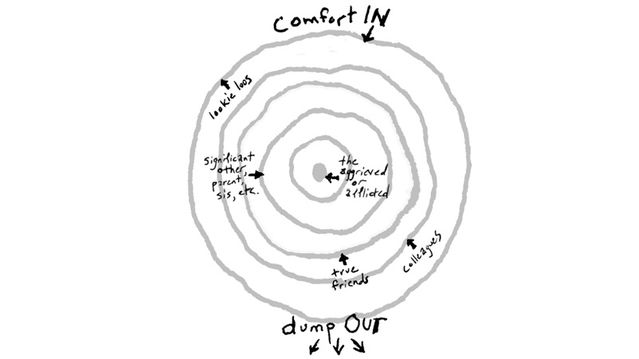

A few years ago, Susan Silk and Barry Goldman penned a wonderful article in the L.A. Times about how to cope with situations involving suffering and grief. They advised to draw a set of concentric circle, with the person directly experiencing the distress at the center, the people closest to them around them, situating people on a continuum to closeness to the situation:

Here are the rules. The person in the center ring can say anything she wants to anyone, anywhere. She can kvetch and complain and whine and moan and curse the heavens and say, “Life is unfair” and “Why me?” That’s the one payoff for being in the center ring.

Everyone else can say those things too, but only to people in larger rings.

When you are talking to a person in a ring smaller than yours, someone closer to the center of the crisis, the goal is to help. Listening is often more helpful than talking. But if you’re going to open your mouth, ask yourself if what you are about to say is likely to provide comfort and support. If it isn’t, don’t say it. Don’t, for example, give advice. People who are suffering from trauma don’t need advice. They need comfort and support. So say, “I’m sorry” or “This must really be hard for you” or “Can I bring you a pot roast?” Don’t say, “You should hear what happened to me” or “Here’s what I would do if I were you.” And don’t say, “This is really bringing me down.”

If you want to scream or cry or complain, if you want to tell someone how shocked you are or how icky you feel, or whine about how it reminds you of all the terrible things that have happened to you lately, that’s fine. It’s a perfectly normal response. Just do it to someone in a bigger ring.

Comfort IN, dump OUT.

Susan Silk and Barry Goldman, How Not to Say the Wrong Thing, Los Angeles Times, April 7, 2013

I mentioned ring theory in my mindfulness meditation course Sheltering in Compassion when we talked about reactivity to pain and fear. Later, my friend Sarah made a really important observation: because on social media one has a large and diverse audience, the rings get “smooshed together.” Some of the people you speak to are closer to grief than you are, and some are farther away.

The pandemic really drives home this “ring smooshing” situation. It is tempting to offer the comparing mind free rein to scan around and assess who got dealt better or worse hands than ourselves. But the comparisons are always incomplete, because while you might have the external parameters of another person’s situation (and sometimes not even that), you do not have their internal experience. Some people might be busier than others, or caring for more people, while others may feel more isolated and lonely. In short: When we complain online, we don’t know whether we are being read by people in a closer or a farther away ring. Being mindful of the impact of our complaints of others, and noticing when we hoard emotional energy, is valuable.

But complaining can have a detrimental effect on our own wellbeing as well as that of others. Recently, I came across Cianna Stewart’s No Complaining project, and read her book (more of a workbook) with great interest. As she points out, hearing oneself complain can generate despair, aggravate depression and anxiety, and, importantly, give the person a sense that they are “stuck in the complaint”, thus divesting us from the power to figure out solutions to our problems. Stewart, who worked in HIV prevention during the AIDS epidemic, knows a lot about the importance of changing the script of a negative, self-defeating narrative.

So, should we clam up and never complain? Should we say that everything is hunky dory at all times? Suppressing or denying all negative experiences and feelings, sometimes extremely manifested as “toxic positivity“, does not make the negative experiences or feelings go away, and ignores an important cue that we are experiencing something meaningful. Any emotion, positive or negative, is our mind’s way of calling attention to something important about the human experience.

Nor does intellectualizing the feeling or telling ourselves stories about it help. Some of the behaviors we frame as “healthy venting” aren’t; they foment the sensation and cause artificial upheaval, propping ourselves up through a sense of righteousness that masks any insights we could draw from a quiet reflection on the situation. So, both expressing and repressing unpleasant feelings can take the shape of resistance to what they have to teach us.

A good way through the muddle is to heed the Buddha’s instructions on right speech (samma vaca), which is part of the Eightfold Path, to abstain from “lying, from divisive speech, from abusive speech, and from idle chatter.” I found lots of fantastic resources and examples of right speech, ranging from Marshall Rosenberg’s well-known classic Nonviolent Communication to Beth Roth’s terrific article about improving communication with her teenage son. In the context of complaining, the elements of right speech can help us discern whether our complaints are making the world (including our own minds and spirits) better:

Is It True? Unexamined emotional upheaval can lead us to be stuck in a rigid view of a situation in which we are 100% right and the other person is 100% wrong. This is seldom true. When I revisit painful conflicts from many years ago, I invariably find that, with the perspective of time, I can open myself to a broader view of the situation. This is not easy to do when I’m “hooked” and in the throes of the strong emotion. All the more reason to sit quietly with the emotion, befriend it, try to find out what it needs or what it wants to teach me, and only then respond. I’ve mentioned here before Byron Katie’s The Work; while I have reservations about how she runs the workshops, I think using this worksheet to process a situation can be helpful as a mind-opening tool.

Is It Gossip? I once visited a Waldorf school , where the principal told me of the school’s efforts to foster a healthy communication culture not only among the students, but among the administrators and teachers. One of their most important communication rules was “go to the source, or let it go.” This prevented gossip from leading to misunderstandings and festering in the community without solution. It also occurs to me, along the lines of Cianna Stewart’s work, that going to the source empowers the person with the grievance to shift the situation in a constructive way, whereas witnessing oneself gossip without solution doesn’t help. I’m going to add to this that “callout culture”, which is sometime hailed as “speaking truth to power,” is not exactly a “go to the source” solution. True, the source will be exposed to what is going on, but so will many others: callouts are a social theater and have an audience. Precisely because of the performative aspect, the supposed benefits of “starting a conversation” or “bringing about a reckoning” usually fail to manifest (I’ve written about this here and here and talked about it here.) Whatever can be resolved with a direct conversation, should, and going behind someone’s back or broadcasting broadly should be done only when there are important considerations that rule out going to the source.

Is It Abusive? Relatedly, complaints should be framed in a constructive way. Lashing out at people, especially in public or behind their backs, or engaging in cynicism and ridicule, is counterproductive. Striving to find a way to say even difficult things with kindness not only encourages a broader view of the situation, but also goes a longer way toward ensuring that our speech has its desired effect.

Is It Necessary? Online discourse has a democratizing feature–the virtual floor is open to anyone who has an opinion and wants to share it. Consequently, we are bombarded with hot takes and opinions from all directions; even when we have good crap detection skills, it is still time consuming and burdensome to deal with the incessant flow of opinions. This pandemic time is teaching me great lessons about the need to be more discriminating in my online communications, if only not to overburden people who are already drowning in a sea of things to read, to process, to engage in. I’ve started asking myself whether what I have to say really adds anything to what is already out there. A related important inquiry has to do with the social footprint of the speaker. My good fortune in life and what I do for a living mean that I often get to hold the proverbial talking stick, and have become mindful of the importance of passing it to voices that receive less than their due attention, or speaking for them if their own voices are muted by tragedy or lack of social advantage (speaking for incarcerated people during this pandemic, for example, is crucially important, because it is hard for the public to get the information firsthand, but whenever possible we should hear from people released from prison and from families of prisoners.)

Underscoring these four guidelines is the fundamental question: Am I expressing myself to deflect, ignore, or rid myself of feelings that have important lessons to teach me? Or am I engaging with my feelings, aware of them, accepting their valuable teachings, and then skillfully considering where my words might have the most beneficial effect? It is not necessarily true that “if you don’t have something positive to say, it’s best to say nothing at all”; sometimes negative things need to be said, pain needs to be voiced and honored, for things to change. Let’s put our precious and valuable words to their best effect.

No comment yet, add your voice below!