A tragedy is playing out in California’s theatre of the absurd, San Quentin Death Row. For the last few days, advocates have watched in horror as COVID-19 ravaged through the prison, likely as a consequence of a mass transfer from Chino of prisoners who had not been tested: as of June 25, 542 cases, all but 30 of them very recent. This morning, the Chronicle reports:

A coronavirus outbreak exploding through San Quentin State Prison has reached Death Row, where more than 160 condemned prisoners are infected, sources told The Chronicle on Thursday.

One condemned inmate, 71-year-old Richard Eugene Stitely, was found dead Wednesday night. Officials are determining the cause of death and checking to see whether he was infected.

State prison officials declined to confirm that the virus has spread to Death Row, but three sources familiar with the details of the outbreak there provided The Chronicle with information on the condition they not be named, and in accordance with the paper’s anonymous source policy. Two of the sources are San Quentin employees who are not authorized to speak publicly and feared losing their jobs.

There are 725 condemned inmates at San Quentin, and of those who agreed to be tested for the coronavirus, 166 tested positive, the sources said.

. . .

It is unclear whether Stitely was infected with the coronavirus. He refused to be tested, according to the three sources with knowledge of the situation.

If Stitely tests postive, his death could mark the first coronavirus fatality in California’s oldest prison, where prisoner cases have rocketed from zero infections in late May to 515 by Thursday evening. Additionally, 73 San Quentin staff members have tested positive.

The infections were touched off by a botched transfer of 121 men on May 30 from the virus-swamped California Institution for Men in Chino, which until Thursday was the state prison with the largest number of infected inmates.

San Quentin has surpassed Chino’s current tally of 507 cases, and now holds more incarcerated people who have tested positive for the virus than anywhere else in the state. There have been more than 4,000 confirmed cases throughout California’s prison systems, with 20 prisoner deaths attributed to COVID-19. Sixteen of those deaths came from the California Institution for Men in Chino.

As of Thursday, there were 16 San Quentin prisoners who were receiving care from outside hospitals because of COVID-19 complications, according to Liz Gransee, a spokeswoman for the prison’s health care system.

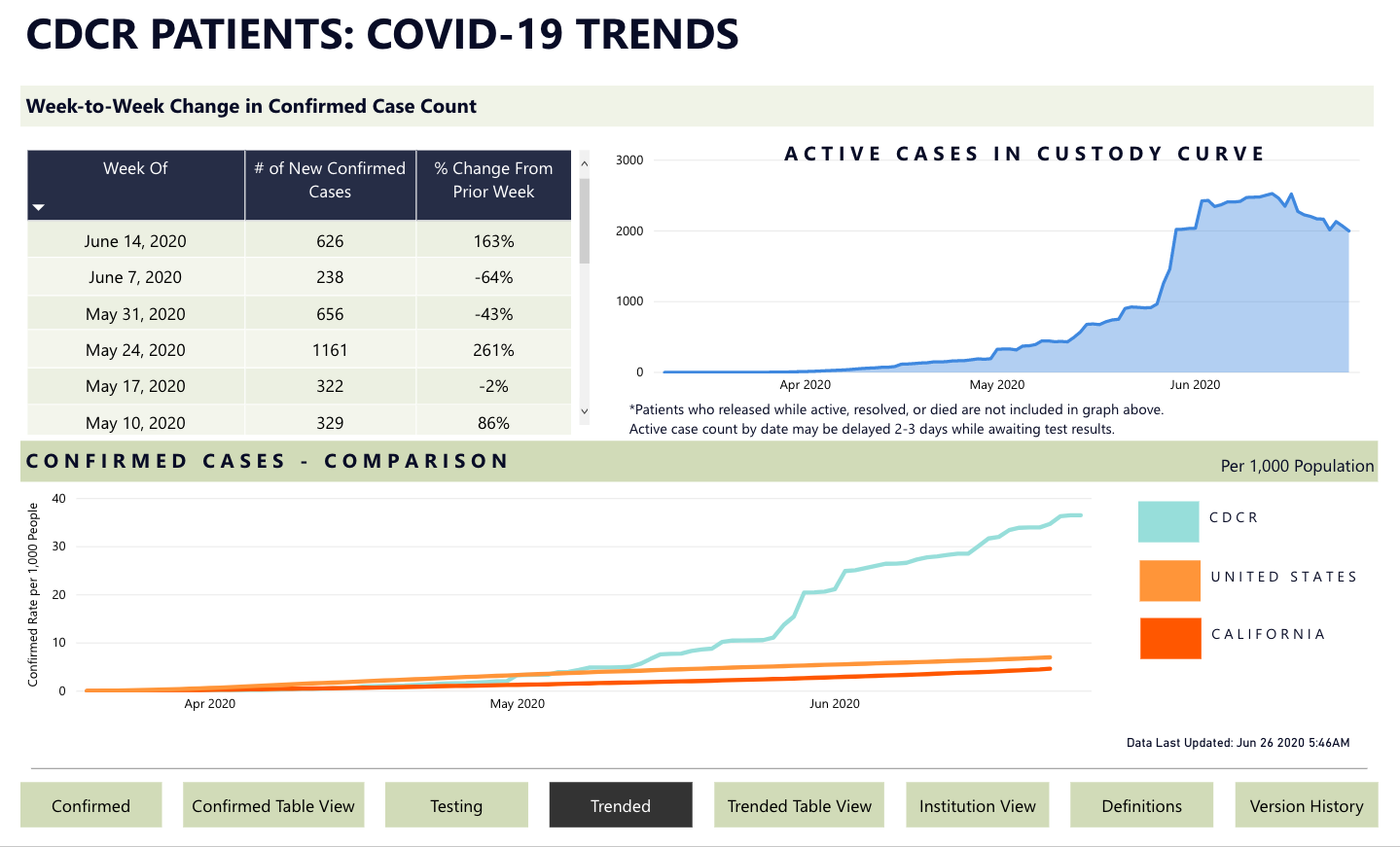

Yesterday I spent some time playing with the infection statistics in CA prisons, trying to correlate them with overcrowding, as well as with infection data from each prison’s surrounding county. The signal-to-noise ratio was too faint to pick anything useful up. I’m going to leave the more fine-grained inference models to epidemiologists; this is something that should be done on a time series, not a snapshot of one day. It’s also useless to infer contagion given the dramatic change, over time, in testing rates, and the considerable differences between prisons in both overcrowding and testing rates. According to the CDCR tool, as of last night only 35.3% of inmates at San Quentin have been tested, and the testing rates range widely, from 97% at Amador to 11.4% at Chuckawalla.

Specifically as to Quentin: As of June 24, the population in prison was 3,507. Design capacity for Quentin is 3,082; they are at 113% capacity. I’m sure some of you will remind me that this complies with the Plata mandate, but the Plata numbers are meaningless in this context, so let go of the mythical 137.5%. What matters is not what federal courts said ten years ago in a different context; what matters is whether there is actual room to isolate and treat people now. If death row isolation, where people are housed in single-occupancy cells, is not sufficient protection from contagion, it is unclear where and how they can make space in an overcrowded general population to maintain social distancing. In any case, it’s way too late for masks and 6-feet-niceties. Let’s play a bit with numbers. With a 35% testing rate at Quentin, we have, say, 1227 prisoners out of 3507 tested. Out of those folks, 542 – an astounding 44 percent – have been found positive.

Now, this does not mean that 44% of the entire San Quentin population is infected. The virus doesn’t pick and choose where to spread, nor does it spread evenly across the prison. The geography and architecture of the prison is key, which is partly why we’re seeing this horror play out specifically on death row. We also don’t know whether the testing protocol follows the infected areas. Recall that the people who spoke to the Chron did so anonymously, out of fear of losing their jobs.

While we cannot (yet?) causally attribute the death in death row to COVID-19, the absurdity of the entire situation is breathtaking. We have a death penalty moratorium after decades of sentencing people to death and then not executing them. We have spent billions of dollars during these decades litigating minute technicalities: death chamber setup, this drug, that drug, one drug, three drugs. Extensive appellate proceedings have gotten into the minutiae of a person’s health because, shockingly, in this country, in half the states, it is still a valid legal question whether someone is healthy enough to be killed by their government. Whatever heinous homicide people committed forty or fifty years ago that landed them on death row, we did not embroil ourselves in endless technical litigation so that people would get their death sentence via COVID.

Nor is it the case, as some people might secretly think, that this is somehow less awful because the people on death row are anyway “the worst of the worst.” Sarah Beth Kaufman’s new book American Roulette, which is out this month, reflects meticulous observations of 16 capital trials nationwide, beginning to end. The people that get the death penalty, as opposed to life without parole, are not necessarily the people who commit the most heinous murders, nor are they necessarily the victims of systemic racism. More likely than not, the question of life or death is decided on the basis of which team puts together the better theatrical spectacle for the jurors, whose selection process already guarantees that they are what Kaufman calls “punitive citizens.” There is nothing that separates the people more and less at risk but misfortune and mismanagement.

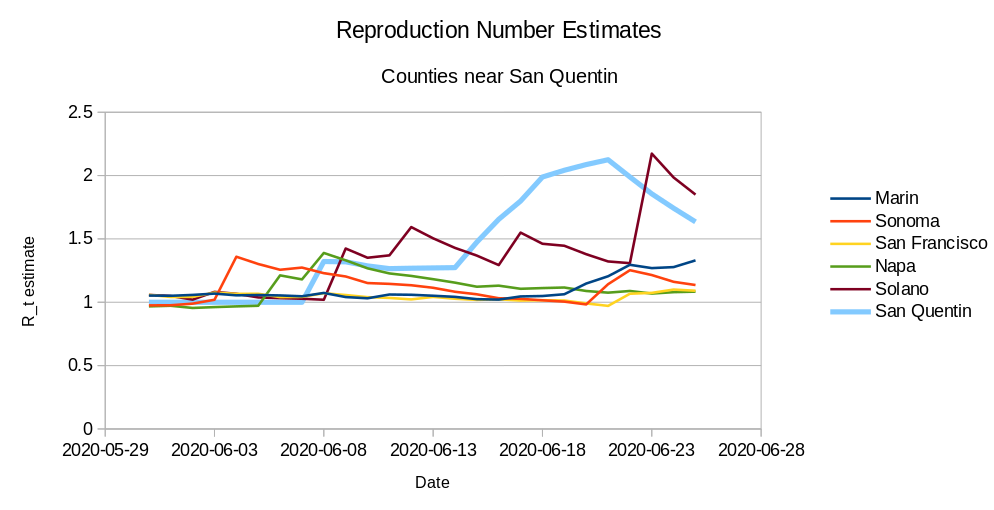

Even if you can’t find compassion for your fellow human beings behind bars, think of you and your loved ones on the outside. California prison guards live in California, and as of yesterday, 73 staff members from San Quentin were infected. We ran some numbers for Quentin as well as for the neighboring counties (the former from CDCR, the latter from the L.A. Times), and the outbreaks in the neighboring counties happened after the transfer from Chino to Quentin. To establish this with certainty you’d need contact tracing, but it is not implausible that guards incubating the disease went shopping or eating around Sonoma, Napa, Solano, or Marin sometime in late May or early June, and that’s what has made Marin’s numbers spike.

Estimated R_t based on new case levels 7 days apart, or a value of 1

in the case of 0 new cases. Smoothed using an exponential moving

average filter with an alpha value of 0.15. Calculation credit Chad Goerzen.

Months ago my colleagues and I repeatedly pleaded Gov. Newsom to release more prisoners than the piddly 3,500 people. I warned that, if we did not do so, CDCR would become a mass grave. Gov. Newsom has seven powerful levers at his disposal to alleviate this crisis: early releases, testing, commutations, ending any collaboration with ICE, parole, resentencing, and funding. UnCommon Law is putting a pressure campaign on titled Healthy and Home. Do what you can to join the calls to aggressively hasten the testing of 100% of the prison population, get home everyone over 50 or otherwise in a high-risk group, and guarantee real health care and preventive measures behind bars.

2 Comments

[…] two previous posts about San Quentin and Susanville finally moved the needle on public attention. After swearing off Twitter, I finally […]

[…] of the “three big reasons” for the outbreak in the Bay Area–as per the graphs in my post a few days […]