Today we learned that there are outbreaks at jails in San Bernardino and Riverside counties, and these have been tied to surges in the community. There is no sign of a COVID stats page on either county’s Sheriff’s Department’s webpage. Why not?

Agnotology, a term coined by Robert Proctor and Iain Boal, is the study of culturally induced ignorance or doubt, particularly the publication of inaccurate or misleading scientific data. In this era of post-truth, studying agnotology, in such areas as climate change and vaccines, can be valuable and instructive.

In criminal justice, we spend a lot of time focusing on the persistence of myths and disinformation, such as myths about racial violence and sex crimes. But our agnotology pays attention, as it well should, not only to misinformation, but also to glaring lacks of information. For example, Franklin Zimring spends a big chunk of his book When Police Kill discussing the huge gaps in data collection about incidents in which police officers kill citizens, and explaining how his analysis required relying on journalistic projects, rather than on official FBI statistics. Similarly, in American Roulette, Sarah Beth Kaufman takes the time and space to discuss the sociological meaning of a lack of any centralized database containing information about capital trials.

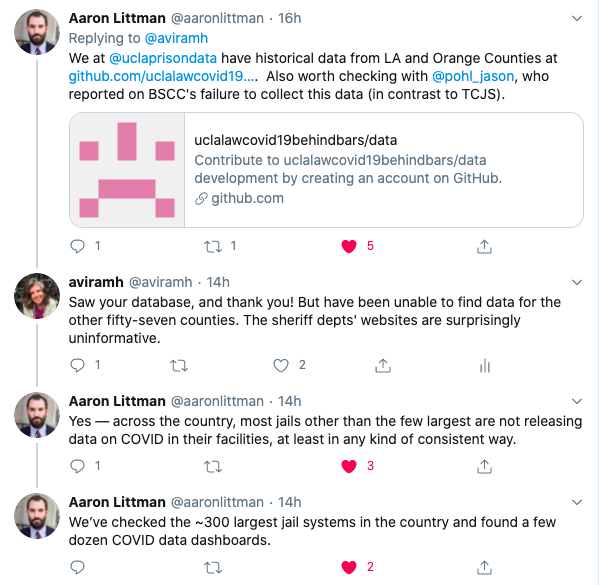

Which brings me to today’s topic: COVID-19 in jails. The UCLA COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project, spearheaded by my colleague Sharon Dolovich, is doing an important service to all of us by collecting longitudinal data on the development of contagion, hospitalization, deaths, recoveries, transfers, testing, etc., for correctional institutions nationwide. If you look at their database, you’ll see impressive coverage of state prisons. County jail coverage, however, is a different story. Yesterday on Twitter we were exchanging notes on the frustrations of trying to find data on COVID-19 spread in jails:

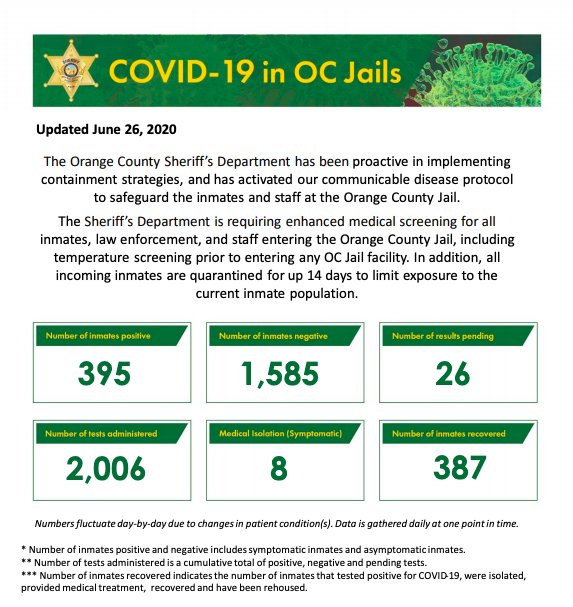

These folks do such a terrific job, and if even they can’t find what we’re looking for, then getting this data is going to be a painstaking job of making requests county-by-county. A few counties, such as Orange and Los Angeles, publicly provide the statistics on their websites. Others, such as San Francisco, send emails to lawyers, etc., when someone in jail tests positive (here are the press releases.) It’s easy enough to find webpages devoted to visiting and testing policies, but the statistics are elusive.

I’m a social scientist, and so lack of information in itself strikes me as an important social fact. When my colleague Margo Schlanger wrote this brilliant piece about the Plata litigation, she expressed concern that shifting control over prison healthcare from one centralized actor, the state, to the counties, would create a “hydra problem”: 59 new, separate sources of healthcare problems. At the time, the thinking was that the state was doing so poorly that surely the counties would be a better solution. In some ways, they were indeed better–that is, as Jeffrey Lin explains, some counties were. In some places, the judges made full use of the option of community supervisions, whereas in others, all the resources and energy went into building bigger jails.

We see the problem of diversification in the way we are getting information. As you saw in my previous posts, CDCR has an excellent and informative tracking tool; one only wishes their actual containment and healthcare management rose to the level of their pandemic documentation. By contrast, in the counties, you’re not dealing with one master, but with fifty-nine. Almost no one is obligated to report, and those who do, do not do it in a uniform manner that would enable us to compare counties effectively.

This is a huge problem for several reasons. The fragmentation of data makes it difficult–perhaps impossible–to track down interactions between correctional outbreaks and spikes in the surrounding counties. For example, we don’t know nearly enough about COVID-19-related releases from jails, nor do we know how to assess the contagion behind bars without clear, accessible information about population, design capacity, and testing protocols. For that reason, it’s impossible to draw connections that are hugely important–especially because jail staff is likely to be coming in and out of the facility into the surrounding county. Moreover, transfers between prisons and jails, which are important points of interface between systems and with the community, remain invisible. In an ideal world, there would be an excellent data interface between the CDCR tool and the county tools, and the latter would all look the same and provide the information that CDCR is doling out (as well they should.) But this is not that world, and perhaps we’ve gotten so used to administrative fragmentation that many don’t see what a hindrance it is.

Jails are not the only place where fragmentation is a problem. A decade ago, Jeremy Seymour, Richard Leo and I wrote a piece called Moving Targets, in which we explained that the fragmentation of police departments in the U.S. allows for all kinds of negligence and shenanigans in which one municipal police department can blame its mishaps on another. The current interest in policing has floated another nefarious aspect of this: cops who beat people up and lie in court might get fired by Department A, but might be immediately rehired by Department B, given that there are no state or federal licensing requirement. “This person beats people up and lies in court in a different municipality” does not seem to be a hindrance to getting rehired; in fact, the glorified disbanding of police departments has led to the county sheriff’s department taking over and rehiring all the cops that the disbanded department fired in the same geographical area. The absurdity goes beyond just cops–incompetent coroners get fired and rehired by other agencies all the time.

What we urgently need is for counties to liaise with whoever is doing the work for CDCR, get the same platform, collect the same information, link their databases, and get to work. This would be incredibly helpful to the good folks doing the work at the UCLA data collection project, but to epidemiologists and to all of us. Until that happens, a word of advice to other folks doing work on this: please, keep in mind this glaring gap in knowledge when you theorize about what is going on behind bars.

2 Comments

[…] couple of weeks ago I posted about the “known unknowns”: the situation in county jails. I don’t think that the […]

[…] a series of newspaper exposés about outbreaks in other CA county jails. As I explained in previous posts, as well as in our open letter to the Governor, save for a handful of reporting jails, reports […]