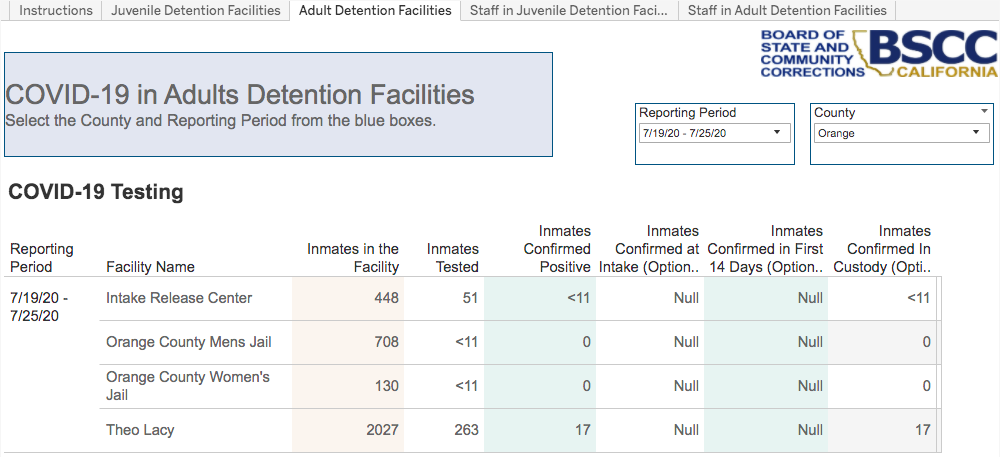

Yesterday, in a 5-4 vote, SCOTUS stayed a lower court’s preliminary injunction that required the Orange County Sheriff to implement certain COVID-19 safety measures. The decision, Barnes v. Ahlman, is brief, with only Justice Sotomayor writing for the dissent (what a superb law-and-society Justice she is–and a fantastic writer.) Before delving into the decision, it’s worthwhile looking at the BSCC reports for the OC, which I’ve placed above. Now, the webpage claims that they updated it yesterday, but it also claims that the numbers we’re seeing are for the week between 7/19 and 7/25, which is adds to my impression that BSCC reporting, which is already woefully late to the game, needs considerable improvement if it is to be informative. For what it’s worth, during that week–and things might’ve exponentially spread since then–the OC jail system had at least 17 cases and had tested less than 10% of their population. Moreover, Justice Sotomayor writes that “[a]t the time of the District Court’s injunction, the Jail had witnessed an increase of more than 300 confirmed COVID–19 cases in a little over a month.” You wouldn’t know this from the BSCC page, because for unfathomable reasons they don’t report cumulative cases, nor do they provide the data they had before the dashboard was created. I really hope that the COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project will be able to obtain better information, including cumulative and historical numbers–apparently the numbers exist, because local newspapers were reporting on them weeks ago–but I’m not holding my breath. In any case, putting together Justice Sotomayor’s summary and the BSCC data points to a worrisome situation: they’ve had hundreds of cases and they are currently doing hardly any testing, which could explain why they numbers seem small.

Anyway, back to the decision. Justice Sotomayor refers to the decision to stay the injunction as “extraordinary.” Ordinarily, the conditions for granting a stay require (1) a “reasonable probability” that SCOTUS will actually grant certiorari to hear the case, (2) a “fair prospect” that SCOTUS will subsequently reverse the decision on the merits, and (3) “a likelihood that irreparable harm [will] result from the denial of a stay”. None of these apply here: the Ninth Circuit ruled on clearly established law–it found ample proof of “deliberate indifference” because the jails were forewarned about this months ago and knew the risks–and, even if the Eighth Amendment is not grounds enough for relief, there is an alternative claim under the ADA. Therefore, odds that SCOTUS will hear this case and reverse are slim. Worst of all, the “likelihood of irreparable harm” is obvious from the facts, described in “dozens of inmate declarations”:

Although the Jail had been warned that “social distancing is the cornerstone of reducing transmission of COVID–19,”

inmates described being transported back and forth to the jail in crammed buses, socializing in dayrooms with no space to distance physically, lining up next to each other to wait for the phone, sleeping in bunk beds two to three feet apart, and even being ordered to stand closer than six feet apart when inmates tried to socially distance. Moreover, although the Jail told its inmates that they could “best protect” themselves by washing their hands with “soap and water throughout the day,” numerous inmates reported receiving just one small, hotel-sized bar of soap per week. And after symptomatic inmates were removed from their units, other inmates were ordered to dispose of their belongings without gloves or other protective equipment. Finally, despite the Jail’s stated policy to test and isolate individuals who reported or exhibited symptoms consistent with COVID–19, multiple symptomatic detainees described being denied tests, and others recounted sharing common spaces with infected or symptomatic inmates.

That the Sheriff’s Department gets to benefit from a pattern of recklessness and obfuscation is sickening in itself, but what’s really sickening is that even as I type this, more cases are preventable. What kind of public official spends their times and resources fighting an order to implement sensible precautions, instead of actually implementing them? BSCC’s feebleness is all over this, starting with the flimsy data collection effort and continuing with these disturbing practices at the county level. The other thing that nauseates me is that there’s no reason to assume that everything is tickety-boo at the other jails, and we now need to expand our list of “known unknowns” at the county level to actual practices of the ground. We can’t make definitive extrapolations from this OC example without knowing more, but if the OC “inmate health and safety” is just a facade, there’s no assurance that other jails are following their own COVID-19 protocols.

1 Comment

[…] held today that the Orange County Sheriff, whose COVID-19 prevention incompetence was featured in Barnes v. Ahlman, violated the Eighth Amendment, and ordered the jail to reduce its population by […]