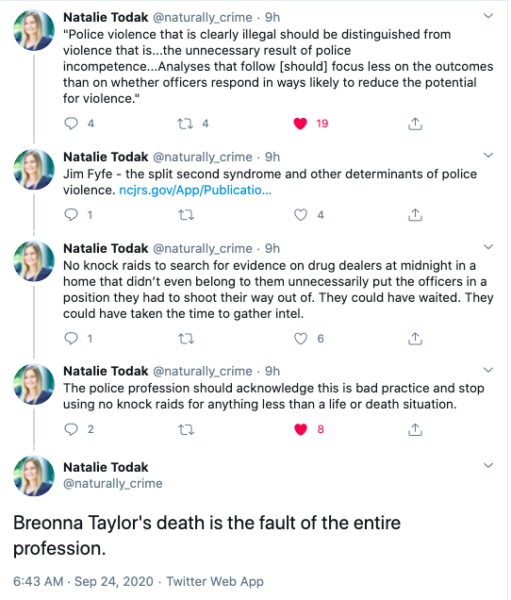

Yesterday we received the news that only one of the police officers involved in the killing of Breonna Taylor was to be indicted–and not for homicide, but for “wanton endangerment” involving shooting toward the neighbors’ homes. Because of the obvious point made by my colleague Frank Zimring in When Police Kill–that the hope to save more lives from police brutality should not be pinned on the criminal process–I want to focus on the question of saving lives, specifically in the context of knock-and-announce. A good starting point is this valuable commentary by my colleague Natalie Todak, who studies policing:

I agree and want to add a few words about how this is not only the fault of police officers, but of the Supreme Court.

You’ve all seen the knock-and-announce rule in action on your TV screens, every time a cop in a police drama loudly yells: “Police! Open up!” What you might not know is that the knock-and-announce rule has ancient roots in common law. In Miller v. United States, officers without a warrant knocked on the door of Miller’s apartment and, upon his inquiry, “Who’s there?” replied in a low voice, “Police.” Miller opened the door, but quickly tried to close it, whereupon the officers broke the door, entered, arrested petitioner and seized marked bills which were later admitted as evidence against Miller in a drug case. The Supreme Court held that “[t]he common-law principle of announcement is embedded in Anglo-American Law” and that Miller’s arrest was unlawful because the police broke in without first giving him notice of their authority and purpose.

The reason for this is obvious. In Wilson v. Arkansas, the court explains: “[A]nnouncement generally would avoid ‘the destruction or breaking of any house … by which great damage and inconvenience might ensue’.” And in Hudson v. Michigan, Justice Scalia expands:

One of [the interests protected by the knock-and-announce requirement] is the protection of human life and limb, because an unannounced entry may provoke violence in supposed self-defense by the surprised resident. Another interest is the protection of property. Breaking a house (as the old cases typically put it) absent an announcement would penalize someone who “ ‘did not know of the process, of which, if he had notice, it is to be presumed that he would obey it … .’ ” The knock-and-announce rule gives individuals “the opportunity to comply with the law and to avoid the destruction of property occasioned by a forcible entry.” And thirdly, the knock-and-announce rule protects those elements of privacy and dignity that can be destroyed by a sudden entrance. It gives residents the “opportunity to prepare themselves for” the entry of the police. “The brief interlude between announcement and entry with a warrant may be the opportunity that an individual has to pull on clothes or get out of bed.” In other words, it assures the opportunity to collect oneself before answering the door.

J. Scalia (Op. Ct.), Hudson v. Michigan (2006)

Granted, in some cases there may be an advantage in hurrying in, because otherwise the police knock on the door can prompt the people inside to destroy evidence–especially in drug cases. But this advantage needs to be weighed against the drawbacks of violence: to mention just two possible scenarios, the police could be making a mistake and trashing the wrong person’s house, or the people inside might mistake them for a rival drug crew and shoot them. Because of these drawbacks, in Richards v. Wisconsin, the Court hesitated to create a special “felony drug exception”, exempting officers from the knock-and-announce rule in all drug cases. They explained:

We recognized in Wilson that the knock and announce requirement could give way “under circumstances presenting a threat of physical violence,” or “where police officers have reason to believe that evidence would likely be destroyed if advance notice were given . It is indisputable that felony drug investigations may frequently involve both of these circumstances. . . But creating exceptions to the knock and announce rule based on the “culture” surrounding a general category of criminal behavior presents at least two serious concerns.

First, the exception contains considerable over generalization. . . not every drug investigation will pose these risks to a substantial degree. For example, a search could be conducted at a time when the only individuals present in a residence have no connection with the drug activity and thus will be unlikely to threaten officers or destroy evidence.

Second. . . the reasons for creating an exception in one category can, relatively easily, be applied to others. . . If a per se exception were allowed for each category of criminal investigation that included a considerable–albeit hypothetical–risk of danger to officers or destruction of evidence, the knock and announce element of the Fourth Amendment’s reasonableness requirement would be meaningless.

J. Stevens (Op. Ct.) Richards v. Wisconsin (1997)

But it’s unclear who the real winner in Richards was. Even though the Court refused to create a blanket exception, the opinion did open the door to special circumstances in which the police might decide not to knock (because of exigent circumstances.) Many of these situations overlap with the exception that the state of Wisconsin sought (and didn’t get.) So we were left with police discretion as to whether to knock and announce or not.

Soon enough, this developed into a practice in which officers anticipated the need to enter without knocking and asked for a carte blanche from the magistrate signing the warrant to do so (so as to cover their asses in case their judgment is questioned at a later date)–and that in itself invited all kinds of shenanigans, such as inventing nonexistent informants to obtain the warrants.

The final blow to the knock-and-announce rule came in Hudson v. Michigan. The main remedy in cases in which the police obtain evidence in violation of the Fourth Amendment is, typically, the suppression of the evidence under the exclusionary rule: the prosecution can’t use it in their case-in-chief. But gradually, the post-Warren courts saw this as a steep price to pay: “the criminal goes free because the constable has blundered.” Because of that, in Hudson, the Court introduced a cost-benefit analysis: The evidence will only be suppressed if the benefit of deterring the police from the undesired behavior exceeds the cost of allowing a guilty defendant to “walk away on a technicality.” Hudson involved a situation in which the police did not knock and announce, and Justice Scalia took the exclusionary rule of the table, arguing that it was not the right fit. While the knock-and announce rule, he said, protected the right of people to be calm and collected when answering the door, it had “never protected. . . one’s interest in preventing the government from seeing or taking evidence described in a warrant. Since the interests that were violated in this case have nothing to do with the seizure of the evidence, the exclusionary rule is inapplicable.” Justice Scalia proceeded to say that the exclusionary rule is no longer necessary:

Another development over the past half-century that deters civil-rights violations is the increasing professionalism of police forces, including a new emphasis on internal police discipline. Even as long ago as 1980 we felt it proper to “assume” that unlawful police behavior would “be dealt with appropriately” by the authorities, but we now have increasing evidence that police forces across the United States take the constitutional rights of citizens seriously. There have been “wide-ranging reforms in the education, training, and supervision of police officers.” Numerous sources are now available to teach officers and their supervisors what is required of them under this Court’s cases, how to respect constitutional guarantees in various situations, and how to craft an effective regime for internal discipline. Failure to teach and enforce constitutional requirements exposes municipalities to financial liability. Moreover, modern police forces are staffed with professionals; it is not credible to assert that internal discipline, which can limit successful careers, will not have a deterrent effect. There is also evidence that the increasing use of various forms of citizen review can enhance police accountability.

This turns out to be untrue. Not only do structural police reforms have mixed outcomes at best, monetary damages are completely meaningless because police officers are indemnified and police departments insured to the hilt. But the real outrage about this decision is the logic that the exclusionary rule has excelled so much in educating police officers about the rights and wrongs of the Fourth Amendment that it’s not necessary anymore. To support this argument, Scalia cited Samuel Walker’s book Taming the System, which showed that the exclusionary rule was an essential component in the reduction of constitutional violations. When Walker heard that Scalia cited his book, he was incensed, and wrote a hilarious-but-irate op-ed in the L.A. Times, titled, “Thanks for Nothing, Nino.” Walker explains:

[Scalila] twisted my main argument to reach a conclusion the exact opposite of what I spelled out in this and other studies.

My argument, based on the historical evidence of the last 40 years, is that the Warren court in the 1960s played a pivotal role in stimulating these reforms. For more than 100 years, police departments had failed to curb misuse of authority by officers on the street while the courts took a hands-off attitude. The Warren court’s interventions (Mapp and Miranda being the most famous) set new standards for lawful conduct, forcing the police to reform and strengthening community demands for curbs on abuse.

Scalia’s opinion suggests that the results I highlighted have sufficiently removed the need for an exclusionary rule to act as a judicial-branch watchdog over the police. I have never said or even suggested such a thing. To the contrary, I have argued that the results reinforce the Supreme Court’s continuing importance in defining constitutional protections for individual rights and requiring the appropriate remedies for violations, including the exclusion of evidence.

The ideal approach is for the court to join the other branches of government in a multipronged mix of remedies for police misconduct: judicially mandated exclusionary rules, legislation to give citizens oversight of police and administrative reforms in training and supervision. No single remedy is sufficient to this very important task. Hudson marks a dangerous step backward in removing a crucial component of that mix.

Samuel Walker, “Thanks for Nothing, Nino,” Los Angeles Times, June 25, 2006

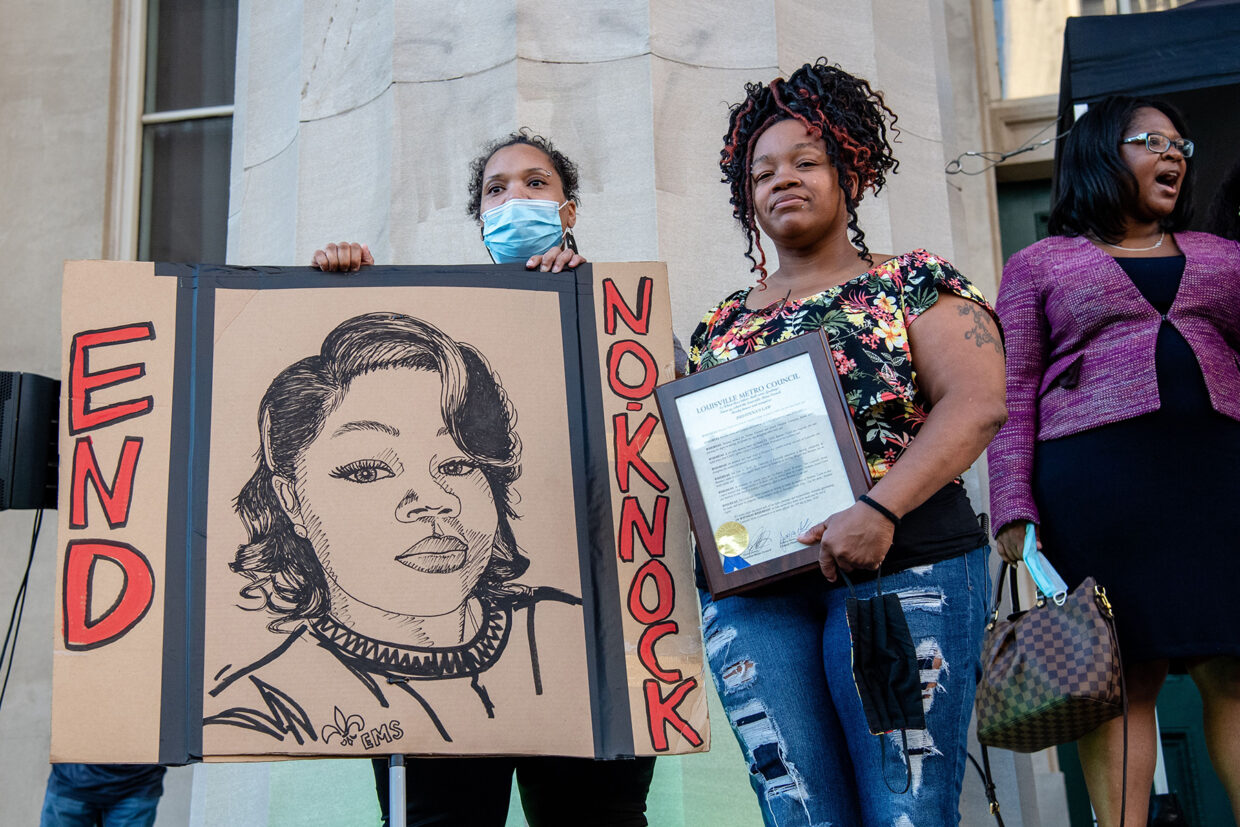

There are now numerous efforts, through litigation and legislation, to outlaw no-knock warrants at the state level. But doing this will not remove the problem. All it will do is forbid the judge from kosherizing the police decision to enter without knocking–a decision that they will still be allowed to make, with no consequences, under Hudson v. Michigan. As long as the Supreme Court does not overturn this decision, the discretion in the field will still be available–and given the post-Warren Courts’ tendency to give officers in the field, making decisions based on “totality of the circumstances”, the benefit of the doubt, the problem will not go away. Not only is Breonna Taylor’s death the fault of the entire policing profession, it is also the fault of the Supreme Court’s lopsided cost-benefit analysis, and I dread to think about the people who will continue to pay the price for these misguided practices.

No comment yet, add your voice below!