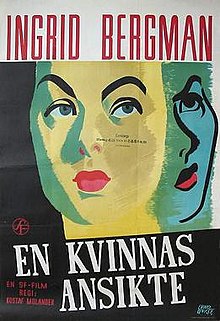

In an effort to set aside the horrors of the present, I am returning to the online Noir City International festival to enjoy this dark Swedish musing into criminality and its causes, A Woman’s Face (1938.) It stars one of my favorite actresses of all time, Ingrid Bergman, in one of her last Swedish roles before being catapulted to Hollywood stardom.

Bergman plays a woman with a disfigured face who leads a criminal extortion gang. When she tries to steal money, she sustains an injury and is caught by the homeowner, a plastic surgeon; he learns more about her and decides to fix her face. His kindness gives her a chance at redemption and at overcoming the trauma of her disfigurement. But the gang has already set in motion a plan that requires her to insert herself as a governess in the home of a dignitary and play a role in the murder of his little grandson so as to affect inheritance plans.

I was engrossed in this movie, which is notable because, as mother to a small child, films with plots endangering children are often too much for me. It didn’t help my blood pressure that the child in question, Lars-Erik, looks and talks a lot like my own son! But the film was captivating because of the origin story of Anna’s criminality. This is not the only noir to suggest that the trauma of physical disfigurement can push people into criminal careers; consider Peter Lorre’s The Face Behind the Mask (1941.) But there are a few notable things here.

Deviance–to the extent that we can even agree on its definition–is complicated. From the 1920s to the 1950s, lots of theories for explaining it emerged, many of them looking at juvenile delinquents’ backgrounds. Some theories attributed it to lack of legitimate opportunities and others to the presence of role models in crime. There’s a wonderful book by James Bennett, Oral History and Delinquency, which goes into how criminologists of the early 20th century dug into people’s narratives about their backgrounds to seek an understanding of how they drifted into criminal behavior. The idea that a person’s experiences, the twists and turns of life, are important milestones in a path toward or away from crime, is again important in criminological theory: life-course criminologists look for milestones in encouraging criminality and desistance.

The thing about narratives, though, is that it’s dangerous to overgeneralize from anecdotes. One needs to systematically analyze life stories of many people to find generalities; not all people who go to college or marry desist from crime, and certainly most of the people who grow up in poverty and trauma don’t go into crime. Which is why the constant reliance on psychological trauma as an explainer of villainry, a-la origin stories of comic book villains, is fascinating and at the same time discomfiting. This is part of what I struggled with when viewing A Woman’s Face: the narrative suggests that Anna’s entry into a criminal life is a direct consequence of her disfigurement, whereas the external remedying of this disfigurement holds the key to her own redemption. It’s a powerful story, and I don’t want to reject its power outright–I know what a difference changes in appearance and external circumstances can make. But I also know some very conventionally beautiful and fortunate people who engage in quite a lot of villainy, so I would enjoy the narrative for its own sake and hesitate to generalize too much from it.

Either way, this is a fantastic flick–far superior, in my view, to the later American remake with Joan Crawford. I hope you enjoy it!

No comment yet, add your voice below!