You may recall that the Court of Appeal’s population reduction order in Von Staich did not specify the method by which CDCR should go about population reduction (though it did strongly recommend focusing on people aged 60 and over with 25 years of incarceration behind them.) The order specified that CDCR could choose to comply via releases or transfers. As far as releases, the recent Chron exposé shows that they delivered more or less on what was promised back in July: far too few people, 99% of whom were getting out in a few months anyway, and only 0.8% of whom were COVID-19 risks.

What this indicates–and what the AG’s petition for review to the California Supreme Court indicates–is that CDCR intends to address this crisis almost exclusively via transfers. This is also becoming clearer and clearer in the Marin Superior Court, where Judge Howard, who is presiding over hundreds of habeas corpus petitions from San Quentin, issued the following order:

SQ Case Management Order No. 12 by hadaraviram on Scribd

The gist of the decision is this: Judge Howard is proceeding with fashioning the remedies, as he considers Von Staich “persuasive authority” and despite declarations from the AG that they do not intend to comply until they hear back from the Supreme Court. At the same time, he seems unsympathetic to the arguments against transfers, because the Von Staich decision “provided clear guidance that transfer was a viable remedy.” The AG representatives did state that, independently of the Von Staich decision, they are starting their own transfer initiative, which targets people aged 65 and older. Judge Howard has ordered them to provide a list of the people they are transferring, and the petitioners’ lawyers to compile a list of people who are aged 60 and over and/or have COVID-19 risk factors.

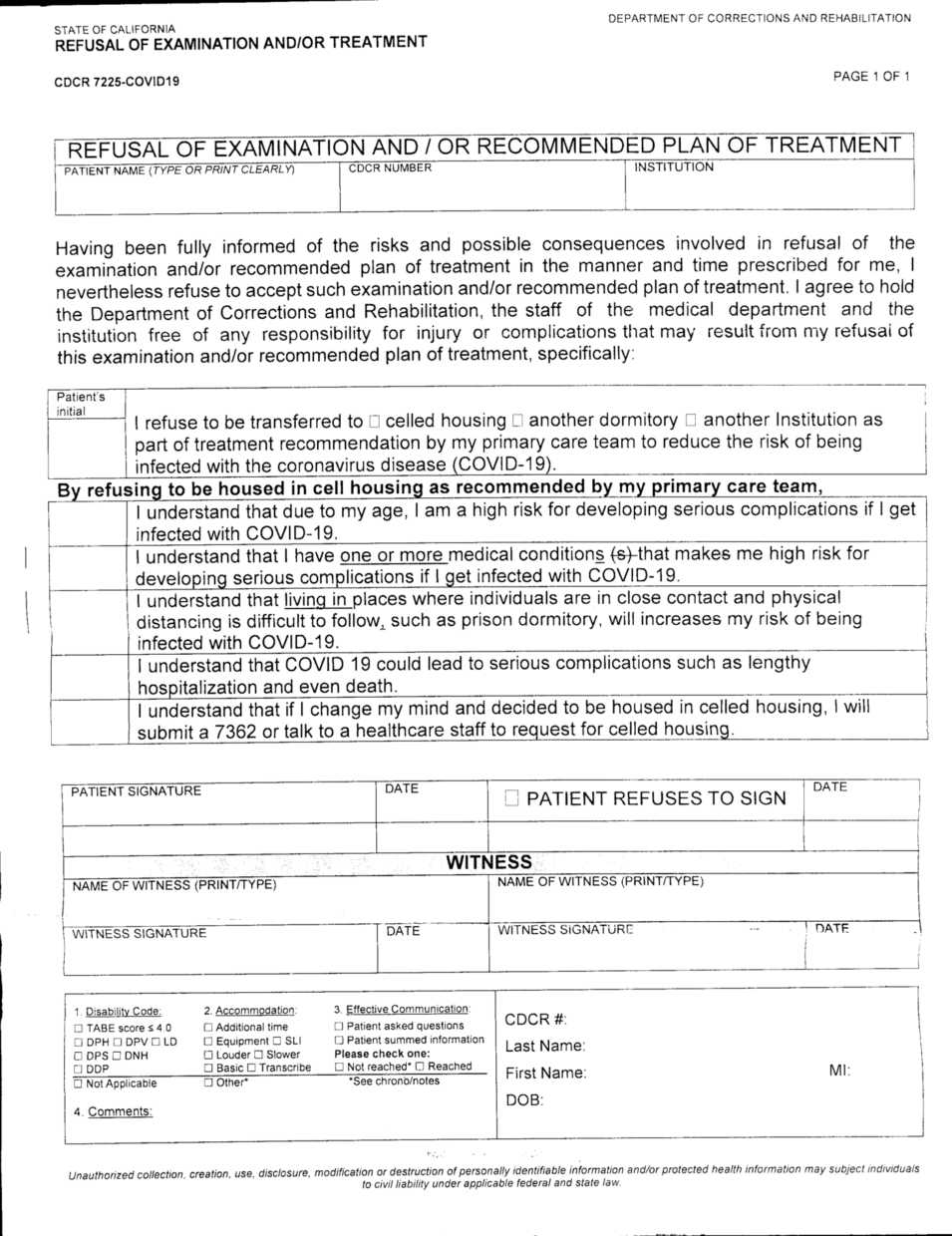

How is this playing out on the ground? You can get a sense from the image at the top of this post. In the last week, per the San Francisco Bay View, people inside–both at San Quentin and at other institutions–have been pressured to accept a transfer out of their own volition, and when they refuse–they are asked to sign the form above, in which they waive any future claims about the risk they face. The form requires them to initial the following statements:

I understand that due to my age, I am at high risk for developing serious complications if I get infected with COVID-19.

I understand that I have one or more medical conditions that makes me high risk for developing serious complications if I get infected with COVID-19.

I understand that COVID-19 could lead to serious complications such as lengthy hospitalizations or even death.

I understand that living in places where individuals are in close contact and physical distancing is difficult to follow, such as prison dormitory [sic], will increases [sic] my risk of being infected by COVID-19.

I understand that COVID-19 could lead to serious implications such as lengthy hospitalization or even death.

I understand that if I change my mind and decided [sic] to be housed in celled housing, I will submit a 7362 or talk to a health staff to request for [sic] celled housing.

I’m hearing from family members and friends of incarcerated people that CDCR is gearing up toward involuntary transfers at Quentin and elsewhere, which are (and always have been) their prerogative, and so, these so-called informed consent forms are actually obsolete. Therefore, it is now more obvious to me than ever that CDCR is worried about a monetary damages lawsuit, and with good reason–I expect we’ll see one in the not-too-far future. If so, I doubt that these waivers, given the circumstances in which they are being procured, will even come close to providing the kind of defense that CDCR, or the AG, think it will provide.

More importantly, the virus doesn’t attend the status hearings at the different courts, and follows its own agenda, which is–as it always has been–to invade cells and replicate itself, which makes this transfer agenda even more inappropriate. As of three days ago, every single CDCR facility has a COVID-19 outbreak, which raises the question–how do CDCR officials purport to improve the situation via transfers, and where are they going to shuffle people to? The information I got from Solano, and a conversation with a relative of someone at SATF, have convinced me that the same pathologies that led to the spread of the virus in San Quentin are now in evidence in other prisons.

Which brings me again to the point of carceral permeability. The logic of lawsuits and court rules doesn’t conform to the realities of geography. By their very nature, they deal with “cases and controversies”, not with proactive solutions to rapidly evolving situations. Order a remedy in one prison, and by the time it’s fashioned, the outbreak will quell there and spike in other places. Exhibit judicial caution and give prison officials the choice between transfers and releases (which is, after all, what courts are supposed to do–express restraint) and they will make the wrong choices. Thinking about this remedy regarding San Quentin alone is part of the brief, but in terms of the actual problem, it makes no sense to implement the remedy in isolation from what is happening in other prisons.

No comment yet, add your voice below!