This morning brings an interesting story by Megan Cassidy of the Chronicle. The story compares two recent cases in which San Francisco D.A. Chesa Boudin brought charges against officers in shooting cases, suggesting that the officers’ inexperience may have played a role in both cases:

The charges against the two men raise questions about whether new officers are being sent into situations they’re not ready to handle and whether different training, more education or older recruits would produce better outcomes. How juries might weigh the officers’ inexperience is an open question.

On Nov. 23, Boudin announced that he had filed manslaughter and other charges against Samayoa, who fatally shot a carjack suspect, Keita O’Neil, during a chase in the Bayview in 2017. The decision marked the first time a San Francisco prosecutor filed homicide charges against an on-duty officer in modern history.

On Dec. 7, Boudin announced that a grand jury had indicted both Flores and the man he shot, Jamaica Hampton, on assault charges after an encounter in the Mission District last December.

“Both cases involved officers who were new to the job, who were relatively inexperienced, behaving in a way that is a stark contrast from the way that other officers on scene with more experience behaved,” Boudin said in a recent interview. “In any profession, including policing, I think when people are new to the job they’re more prone to make mistakes.”

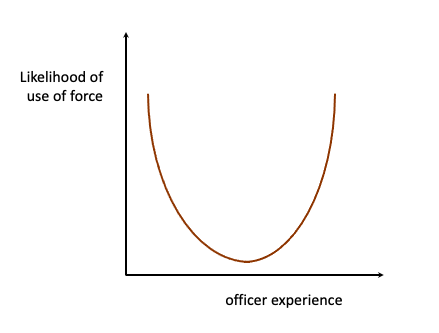

I wonder whether the relationship between experience and police professionalism is truly linear, and my suspicion is that experience and use of force correlate in a different way.

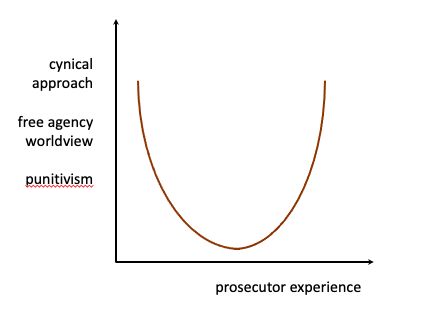

Here’s what makes me think of this: Seventeen years ago I conducted fieldwork in the Israeli military justice system, where I got to interview dozens of prosecutors about charging and prosecuting AWOL cases. Lots of interesting stuff didn’t make it to the eventual pieces, including a typology of the folks I interviewed by seniority. My impressions at the time were of a u-shaped curve in prosecutorial approaches:

When I interviewed very young prosecutors, they tended to espouse a pretty cynical approach about the AWOL cases. They were likely to discount people’s personal problems and socioeconomic situations and ascribe their absence from service to a manipulative personality and free choice. Accordingly, they tended to ask for harsh sentences.

Folks with more experience–say, in the 5-to-15-years range of experience, were more lenient. They tended to have a more holistic view of the person’s circumstances and expressed more mature approaches toward the solutions–some of them saying that without a comprehensive socioeconomic overhaul the problem of AWOL in the army will not resolve itself. But higher up in the seniority ladder, the high-command folks with 20-25 years of experience expressed sort of a return to the punitive approaches of the young ones–not in the same gung-ho manner, but rather as a bird’s-eye view of what the office policy toward these cases should be.

It wouldn’t surprise me if we saw a similar u-shaped curve correlating seniority/experience with the likelihood of use of force among police officers. Let’s think back of William Muir’s terrific book about police officer personalities. Muir posited four types of police officers’ approaches to their jobs, based on where they are located along two perpendicular axes: interventionist-versus-reactive and professional-versus-personal.

The most salient and critiqued problems with U.S. policing lie in the top left quadrant: folks who are interventionist and see things personally (“enforcers”) excessively relying on use of force (as an aside, I’ll propose that “reciprocators” or “avoiders” – the folks in the bottom left quadrant–can put lives in serious danger, too, but this problem is obscured by the shallow way in which we talk about policing.) But let’s take this a step forward. Could it be that these personality types are not innate, but rather stages in the development of one’s career? Let’s hypothesize:

Why young police officers, who might’ve joined the police force in part looking forward to the power that comes hand in hand with the job, may be more likely to use force is pretty obvious. They are younger (like most of the people they police), whatever deescalation training they’ve received requires maturity, and they are more likely to relent to peer pressure, be less thoughtful about future consequences, or respond intuitively to disrespect.

For many police officers, this might mellow out mid-career; their experiences on the streets might lead them to adopt a “tragic” rather than “cynical” approach toward the human experience (to use Muir’s terminology.) Then, for officers with lots of experience and high seniority, signaling toughness through support for violence would be an important way to appeal to the perceived demand of constituents that they “protect and serve.” Just like with the prosecutors, I expect the penchant for violence to be more intuitive/personal in the early stages of one’s career and more systemic/strategic in the later stages.

I don’t know if this is true, but I do know that, while the most senior folks are typically in management roles, the younger and mid-career folks are on the streets. Moreover, officers with less seniority get the less desirable positions and beats, and nonetheless express more enthusiasm for the job–which might imply that we’re putting people with more enthusiasm for violence and a lesser ability to consider consequences in the toughest places.

If that’s the case, how do we make lessons about deescalation “stick” once the officer is out of police academy? Every year, one of the first cases my criminal procedure students read is City of San Francisco v. Sheehan. I’ve written about this case here and here, and in the latter post I quote this paragraph from the decision:

San Francisco trains its officers when dealing with the mentally ill to “ensure that sufficient resources are brought to the scene,” “contain the subject” and “respect the suspect’s “comfort zone,” “use time to their advantage,” and “employ non-threatening verbal communication and open-ended questions to facilitate the subject’s participation in communication.” Likewise, San Francisco’s policy is “‘to use hostage negotiators’” when dealing with “‘a suspect [who] resists arrest by barricading himself.’”

Even if an officer acts contrary to her training, however, (and here, given the generality of that training, it is not at all clear that Reynolds and Holder did so), that does not itself negate qualified immunity where it would otherwise be warranted. Rather, so long as “a reasonable officer could have believed that his conduct was justified,” a plaintiff cannot “avoi[d] summary judgment by simply producing an expert’s report that an officer’s conduct leading up to a deadly confrontation was imprudent, inappropriate, or even reckless.” Considering the specific situation confronting Reynolds and Holder, they had sufficient reason to believe that their conduct was justified.

Let’s set aside the qualified immunity problem. What I want to know is: what makes a violent reaction more innate than the nonviolent, deescalating one? And more importantly, how to we engrain the ability to make space for a different choice in what is often a split-second decision?

In mindfulness meditation, we train the mind to identify moments and circumstances in which we are “hooked” and the mind takes us to a knee-jerk response. Tibetan Buddhists call this moment “shenpa.” Pema Chödrön, one of the people I most respect and admire, says this about the need to make space to choose a different reaction:

If we started to think about and talk about and make an in-depth exploration of the various wars around the world, we would probably get very churned up. Thinking about wars can indeed get us really worked up. If we did that, we would have plenty of emotional reactivity to work with, because despite all the teachings we may have heard and all the practice we may have done, our knee-jerk reaction is to get highly activated. Before long, we start focusing on those people who caused the whole thing. We get ourselves going and then at some irrational level, we start wanting to settle the score, to get the bad guy and make him pay. But what if we could think of all of those wars and do something that would really cause peace to be the result? Where communication from the heart would be the result? Where the outcome would be more together rather than more split apart?

In a way, that would really be settling the score. That would really be getting even. But settling the score doesn’t usually mean that. It means I want my side to win and the other side to lose. They deserve to lose because of what they’ve done. The side that I want to lose can be an individual in my life or a government. It can be a type or group of people. It can be anything or anyone I point the finger at. I get quite enraged thinking about how they’re responsible for everything, so of course I want to settle the score. It’s only natural.

We all do this. But in so doing we become mired in what the Buddhist teachings refer to as samsara. We use a method to relate to our pain. We use a method to relate to the underlying groundlessness and feelings of insecurity. We feel that things are out of control, that they are definitely not going the way we want them to go. But our method to heal the anguish of things not going the way we want them to is what Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche calls pouring kerosene on the fire to put it out.

We bite the hook and escalate the emotional reactivity. We speak out and we act out. The terrorists blow up the bus and then the army comes in to settle the score. It might be better to pause and reflect on how the terrorists got to the place where they were so full of hatred that they wanted to blow up a bus of innocent people. Is the score really settled? Or is the very thing that caused the bus to be blown up in the first place now escalating? Look at this cycle in your own life and in your own experience. See if it is happening: Are you trying to settle the score?

Acting out of this knee-jerk place of “settling the score” is not unique to cops, of course, but you can see how someone young and inexperienced might have a difficult time making space in their own mind to make a different choice. And indeed, there are already people doing this work and seeing positive results, not only in decreasing burnout and stress but in inviting compassion and a “tragic” rather than “cynical” worldview. This can relate directly to the tendency to use violence. As Jill Suttie explains here, “A stressed-out police officer will be more likely to resort to intimidation or aggression when confronted with ambiguous situations, which can lead to inappropriate or even violent actions.” She cites Oregon police officer Richard Goerling, who leads the training, and who explains this very well:

“Mindfulness opens up the space in which we make decisions—we’re not so linearly focused or so stressed because we are under threat,” he says. “We may still be under threat, but because I’m regulating my stress response and my emotions—anger, fear, and ego, which is a huge problem in our culture—I’m more aware of my options.”

How this relates to career stage is evident from this passage:

Goerling believes that police need this kind of training in emotional health, because they too often get the wrong message about their job and the way emotions play a role in it. Instead of understanding the impacts of stress, anger, or fear, they try to tamp down those emotions or ignore them, which keeps them from understanding the effect of emotion on performance.

“It’s classic compartmentalizing, saying, ‘I don’t let my emotions get in the way,’” says Goerling. “Yeah, right. But what happens if those emotions spike up out of the little box and get in the way, creating problems in the encounter with others?”

Another problem, says Goerling, is that stuffing down emotions can make one more jaded with time, leading to a sense of being inauthentic, emotionally cut off from other people, and depressed. Though originally he rejected the concept of training officers in self-compassion—a mindfulness practice of directing love toward oneself—he later realized how important it was for keeping officers whole, not to mention the positive interpersonal benefits.

“This whole notion of self-compassion is huge,” he says. “It doesn’t take long in this business before you pretty much dislike everyone around you, and then you begin to dislike yourself, and then you wonder why the grizzled police officer seems to have no affect and seems to be the classic asshole cop.”

“Being tough means investing in ourselves, in actually loving people and wanting to serve them, and in feeling all of our emotions—being able to say that I’m angry, I’m disgusted, I’m sad, I’m joyous,” Moir [El Cerrito’s Chief of Police] says. “What’s remarkable to me is that my officers are seeing it: Between stimulus and response there lies choice.”

The cops in Suttie’s story were nearing retirement, and while this stuff is useful to anyone at any age, I really hope that these skills become a key part of training new police officers at the academy. There’s nothing to say that younger, newer officers can’t learn these skills–children as young as 3 can be taught to meditate (my 3-year-old son can do a 10-minute body scan before he falls asleep.) Mindfulness training for police officers should focus not only on formal meditation, but also on go-to instantaneous practices–even something as mundane as feeling your toes inside your shoes for a brief fraction of a second can bring one back into the body and offer a choice out of the whirlwind of the mind. And, teaching these skills as part of police academy gives people tools for life that they can later use throughout their career, and which can help with their personal lives as well.

No comment yet, add your voice below!