*** UPDATE: I just heard from the researchers that they won the lawsuit and got their data. They shared that “[t]he judge told off CDCR in no uncertain terms.” I’m leaving the post up because some of you may need it to get data from CDCR in the future.***

I just found out something that upset me greatly: Back in May, the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) refused to provide a team of researchers access to parole hearing transcripts because they didn’t like their findings from a previous study. Nichoas Iovino from the Courthouse News Service reported:

In April 2018, four researchers requested 15 years of parole board hearing transcripts and race and ethnicity data for parole candidates from 2002 through 2017, later expanding their request to cover records through Nov. 1, 2019. The researchers from the University of Oregon and Stanford University intend to develop a machine-learning platform to help analyze and detect patterns of bias in California parole decisions.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) released the hearing transcripts but refused to disclose records on race and ethnicity, arguing state law does not require it to turn over information that “would constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.”

The department also refused to release the data through a separate “research review” process after a Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) administrator said she disagreed with University of Oregon researcher Kristen Bell’s prior findings of racial bias in parole decisions for people sentenced to life as juveniles.

In October 2019, the board’s executive officer Jennifer Shaffer said she disagreed with Bell’s conclusions and objected to her research being used in legal filings to oppose CDCR’s positions in court cases, according to the lawsuit filed in San Francisco County Superior Court on Wednesday. Shaffer also reportedly said she would only release the requested records if Bell was no longer involved in the project.

Before going into the problem of viewpoint discrimination and how it chills correctional research, I want to point out the simple fact that, under the California Public Records Act, parole hearing transcripts are public. In fact, on its very webpage, CDCR states that they provide free electronic transcripts upon request, and printed copies for a reasonable fee, as they should, because there’s no need for a FOIA request for parole transcripts.

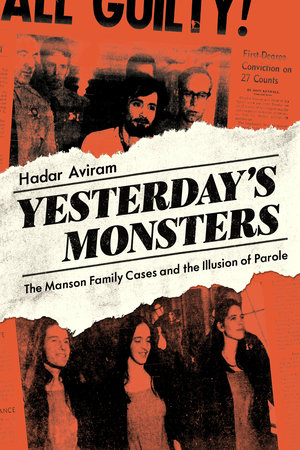

In Yesterday’s Monsters I qualitatively analyzed parole hearing transcripts for seven people, spanning almost 50 years.

I contacted CDCR and requested all hearings for all original members of the Manson Family who have been incarcerated at CDCR. For a reasonable fee, and without giving me any grief at all, CDCR, to their credit, did exactly what they should have done: they put everything I needed on a CD and mailed it to my office address. Within two weeks, I had all the archival materials I needed for transcript analysis.

The complaint is worth reading in its entirety (here it is) and the notion of censoring a particular researcher because their previous findings are not to your liking is outrageous. But, as someone who has worked with the very materials the Oregon and Stanford researchers are trying to obtain, my question is this: If you’re heading an agency and qualified, capable, expensive people tell you that they have the capability to apply machine learning to your agency’s output and find whether you guys are discriminating on the basis of race, wouldn’t you want to take them up on it?

First, even if one believes that race is “irrelevant,” as Ms. Shaffer does, to parole decisionmaking, aggregate analysis can reveal a different picture. My book did not include quantitative linguistic analysis, and it only examined the cases of seven people, all of whom were white, but even so, the interviews and the transcripts raised racial concerns. One of the lawyers I interviewed–Keith Wattley, executive director of UnCommon Law, pointed out that when he represents a client who is a large African American man the Board often says, “you look angry.” Keith, who is himself a large African American man, finds himself often trying to educate the Board about racial stereotypes (this, by the way, is exactly the sort of thing that a machine learning method can help flag.) In addition, I found out that mischaracterization of fights between racial groups/gangs was also a theme. Year after year, the Board denied parole to someone who was the victim of the Aryan Brotherhood because of his “involvement in a fight with a baseball bat” (he was attacked with the baseball bat.) This sort of commentary comes from Board members of various races and ethnicities, and there’s a plausible explanation: even though the Board is diverse in terms of gender and race, it is not diverse in terms of professional background. Almost all BPH commissioners come from a law enforcement background, either in a police or sheriff’s department or in corrections. That racial biases exist among law enforcement officers of color is not exactly news, and for the history of this, read James Forman’s Locking Up Our Own or this wonderful review by Devon Carbado and Song Richardson. Why would law enforcement officers with decades of experience in Petri dishes of implicit bias not take the bias with them into the parole hearing room?

Second, if your agency does not racially discriminate, why wouldn’t you want to prove it via a quantitative, empirical study? You can always dispute the methods, but you’ll have more control over how the algorithm is used if you cooperate. If you deny the information, doesn’t that tell all of us that you’re concerned about what the team may find?

And third, if the study happens to find that there is racial discrimination in parole grants, wouldn’t you want to know this, so that you can do better? It makes me heartsick to consider all the situations in which agencies–particularly correctional agencies–that don’t want to look bad sandbag research projects that can help them actually be less bad. As one example, recently I was struck by the complete absence of any attitudinal research about correctional officers. Last week I sat through a long case management conference in which the judge, CDCR lawyers, prison lawyers, and CCPOA lawyers all wondered, how could it possibly be that the guards are not wearing masks, getting tested, or agreeing to get vaccinated. Judge Tigar asked, “does anyone have thoughts on this?” Crickets. Sheesh, amigos, wouldn’t it come in handy, for example, to have a survey of Trump support among correctional officers? Or a survey about the prevalence of COVID denialism among correctional officers? Don’t you think that would help craft the strategy for gaining compliance, and in the future, guide some hiring decisions? Don’t you think that reluctance to follow science-based healthcare guidelines is a relevant consideration in hiring, retaining, and promoting personnel who work in congregate settings with a chronic health care problem? Wouldn’t you want to include some parameters measuring racism and support for autocracy in your interviews, surveys, or other recruitment tools?

I very much hope the EFF prevails in this case and the research team receives the information they are legally entitled to. My hope with Yesterday’s Monsters was to start a public conversation about parole–especially when we’re faced with big questions about the exit door of prisons in times of crisis, this conversation must continue.

No comment yet, add your voice below!