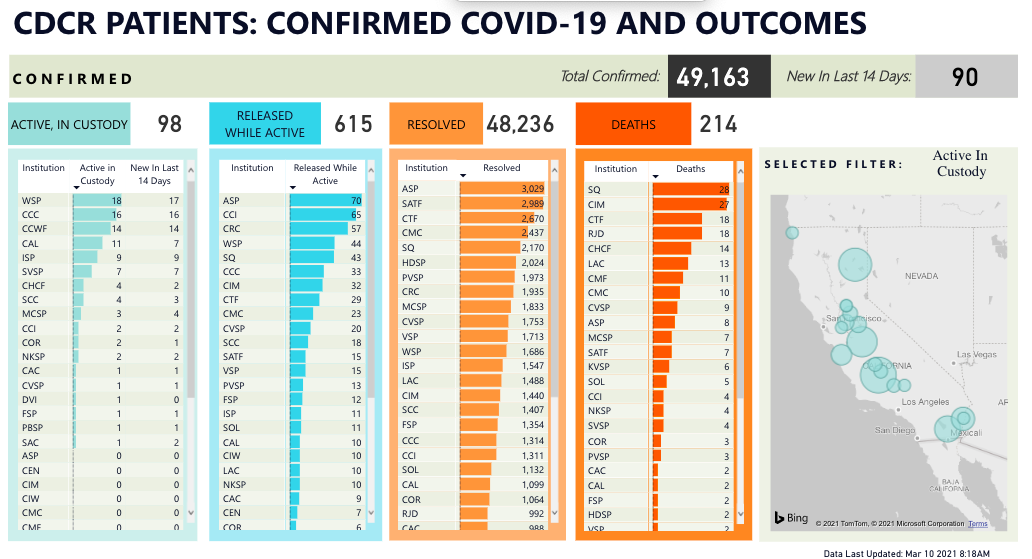

For the first time in a year, there are some good news for CDCR facilities: As of this morning (see screenshot above) there are only 98 active COVID cases in the system, 90 of which are from the last 14 days. There are no new or major outbreaks in any of the prisons. For the first time in 11 months, CDCR’s case rate (95 new cases per 100k people) is lower than California’s (138 per 100k people.)

This situation is largely attributable to two factors: the vaccination rate at CDCR facilities, which is considerable (as of last month, more than 40% of the prison population had received at least the first shot) and, sadly, the herd immunity reached in some facilities with colossal infection rates, like Avenal and San Quentin (which, by the way, has been rightly chastised by OSHA to the tune of $400,000 in fines).

This reprieve could very well be temporary. This week, the CDCR population grew by 85 people (presumably transferred from county jails.) As Chad and I reported a few days ago, the transfers from jails in October and November correlated with outbreaks: 12 out of the 13 prisons whose population grew (presumably jail transfers) experienced subsequent outbreaks (the 13th facility had a big outbreak anyway.) The concern is that jail populations, whose vaccination process has been uneven and erratic, could restart the pandemic in prisons (and that’s beyond the concerns about the serious outbreaks in the jails themselves.) By contrast to prisons, which are operated by the state, jails are operated by the counties, and there is no state mandate requiring counties to prioritize their jail populations in their vaccination protocols.

I have a new piece on SSRN about the place of jails in the California COVID-19 crisis, which argues that BSCC must become the hero we need at this hour. BSCC must lobby the Governor’s office for a state mandate to vaccinate jail populations on a rolling basis, and put pressure on sheriffs to lobby their own counties for vaccine priorities. Vaccination must be a condition of employment for correctional staff and other jail workers. I hope you’ll read the whole thing, but if you’re short on time, here’s the abstract:

This Article examines a lesser-known site of the COVID-19 epidemic: county jails. Revisiting assumptions that preceded and followed criminal justice reform in California, particularly Brown v. Plata and the Realignment, the Article situates jails within two competing/complementary perspectives: a mechanistic, jurisdictional perspective, which focuses on county administration and budgeting, and a geographic perspective, which views jails in the context of their neighboring communities. The prevalence of the former perspective over the latter among both correctional administrators and criminal justice reformers has generated unique challenges in fighting the spread of COVID-19 in jails: paucity of, and reliability problems with, data, weak and decentralized healthcare policy featuring a wide variation of approaches, and serious litigation and legislation challenges. The Article concludes with the temptation and pitfalls of relying on the uniqueness of jails to advocate for vaccination and other forms of relief, and instead suggests propagating a geography-based advocacy, which can benefit the correctional landscape as a whole.

There are two advocacy angles unique to jails. The first is the transience of jail populations: people can stay in jail for periods ranging from a few days to years. This means transmissivity between jails, prisons, and the community is a challenge. The second, which I offer with some hesitation,* is that 75% of jail residents are pretrial detainees, who under our legal system are presumed innocent–all the folks who are muttering about how people in prison “deserve” to get sick, or “should have thought of this before they committed the crime,” do not have even that horrible argument where jail populations are concerned.

BSCC’s function throughout this crisis was neglectful at best and catastrophic at worst. For months on end, they let huge outbreaks go unrecorded and unaddressed, did not hold sheriffs accountable, and did not maintain data for the public. Even now, their database is shamefully clunky and does not interface with CDCR’s. Many counties are not even reporting their numbers. Now’s the time for BSCC to step up and prevent the next outbreaks.

*The hesitation comes from the fact that innocence or lack thereof, or any other variant of deservedness, should not be conflated with healthcare factors. Convicted prisoners should not be a lower priority because of their guilt.

No comment yet, add your voice below!