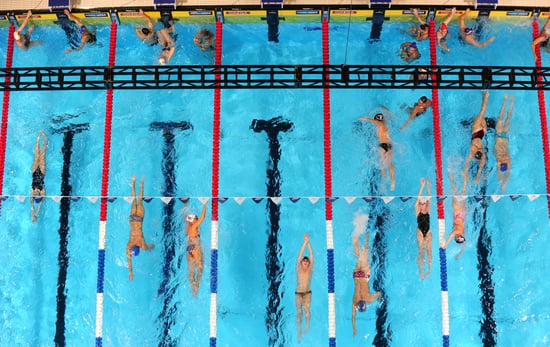

The number of letters, emails, calls, etc., I got after I published this was truly moving overwhelming. It looks like many advocates and activists share a sense of immense exhaustion and feeling unwell and many of us want to get better. For me, as you know, this journey includes total commitment to a whole-food, plant-based diet and to daily outdoor exercise: running, cycling, and swimming. The last of these is the only one at which I’m a veteran; before I semi-retired from the sport in 2016 I was an open water marathon swimmer. These days, for practical reasons (little boy and full-time job=> no time to schlep to the bay, acclimate, and then pour hot tea down my gullet to defrost myself) I swim for no longer than an hour in one of our city pools.

We don’t have many public pools; the ones we have are beautiful and the staff is great, but there is a serious nationwide lifeguard shortage. This means opening hours are extremely limited and the pools get crowded. It’s become rare to have only one person to split a lane with, let alone have the whole lane to yourself. At one of the pools I swim in, there are regularly at least five people to a lane. In the other it’s about three and four. Because these are strangers, not masters teammates, the lanes aren’t calibrated to people’s exact pace, and the fast/medium/slow lane categories are completely arbitrary. Bottom line – I regularly end up in a lane with people who swim either faster or slower than me. Many of the slower folks are delightful people who stop at the pool end to let you pass them, but unfortunately not everyone has the proprioception or the humility to do it. And so, sometimes I get stuck behind folks who really should know better and who make it impossible to pass them (I should say – because I know firsthand the aggravation this causes, when I swim with faster folks I’m hyperconscious of them and let them pass at every opportunity!).

I’ve narrowed the possible coping strategies to five, and some of them are better than others:

- Do nothing and fume. Or, do nothing and slap the water in rage, or kick a little extra hard to vent your frustration. This does not help – not at all – and essentially the only person I punish by marinating in my anger over this is myself.

- Appeal to higher authorities, namely, to the lifeguards and ask them to reorganize people by lane. This is kind of drastic – I’ve never done it myself nor have I seen it done in city pools. At some private clubs I’ve swum in, the lifeguards are experts on tactfully doing this, but it also carries the frustration of dealing with your problem through third parties rather than practically resolving it yourself.

- Change lanes mid-lap and swim back. Here’s how this works: You swim behind the slow person for as long as conceivably possible (to earn yourself some good laps later) and then, right before the wall, shift to the other lane and swim away fast. This obviates the need to confront the other person in any way, and if they are clueless it won’t upset them, either, but you could run into problems confusing the slow swimmer or other swimmers and, in some situations, could be a bit dangerous.

- Aggressive mid-lap pass. This is an emergency move, and an undesirable one, but sometimes people don’t leave you much choice. You carefully check if there’s anyone coming toward you in the opposite lane (i.e., that the other swimmers are already behind you) and them quickly shift to the left lane and beat the slow swimmer to the wall. Beyond the obvious risk, this is also a physically aggressive move and I would not be surprised if it upset and scare the slower swimmer.

- Confront the person at the wall, either through body language (touch their foot lightly, shift to the middle of the lane to block their turn) or actually say “can I pass?” I’ve never seen anyone manifestly refuse to let another person pass after a confrontation, but for a lot of people who look forward to their pool time as their happy place, it could be several laps before the work out the nerve to do it (now that I think about it, I bet there are cultural differences in pool behavior between different countries).

The wisdom we should all cultivate (I’m working on this myself, yo, so don’t think I’m anywhere close to circle swimming nirvana!) lies in deciding which of the five approaches is appropriate for each situation. For example, I think that option 1 is only good when you have a few minutes of cooldown before your workout is over, and then it’s best to channel your frustrations into working on your butterfly or backstroke or do a couple of leg laps without fins, which slows you down coming into the wall. Option 2 is only good when you’re at a pretty hierarchical or at a pretty expensive facility. As to options 3-5, their desirability depends on who you’re dealing with, and here it’s worth remembering that you don’t actually know the person from Adam, and that behind the cap and goggles, “slow-ass” might actually be a lovely person on whom you’re unfairly projecting the frustrations of your day. It’s quite possible to choose the wrong strategy and add unnecessary stress to what should be a blissful hour for everyone–which is where self-compassion and compassion for others comes in, bigtime.

I think about this stuff a lot when I’m in the water, and a couple of days ago, while discussing this with a friend, I realized that these ways of handling conflict with someone you don’t know have recurred elsewhere in my life, especially in the context of prison advocacy. As I work on our book in progress about COVID-19 in California prisons, I’m realizing that a lot of stuff has been happening, at the state and at the county levels, behind the scenes, and while we were privy to the horrific outcomes of all this through the information we got from our incarcerated friends and family members, we were not exactly privy to the inner workings at CDCR or at the Receiver’s office. We know that they paid no heed to the AMEND report, but did they consult with anyone else? It seemed not from the Quentin litigation, and it seems not from the Plata litigation, but surely not everyone who works there is pure, unadulterated evil, and we need better information about internal disputes and conflicts on how to manage this. We know, for example, that the rank-and-file physicians at Quentin were clamoring to save lives (I’ve spoken to prison workers and many of them are decent, conscientious folks who have had a horrific time for the last year and a half.) We also know that various county jail officials worked extremely hard to make vaccination available to their population (this I know firsthand because they consulted me, and they impressed me as being decent people who were well aware of their responsibilities.) I actually don’t know, and have no way of knowing, whether the top brass at CDCR, CCHCS, and CCPOA sleep well at night. And the problem is that the best approach to getting this pandemic under control as numbers in prison are beginning to rise again depends a great deal on understanding these people and where they come from, and on figuring out how to best work with them, around them, or against them.

Over the course of this struggle, I had some experience doing variations on all of these themes. The litigation, of course, is full of animosity; all the media work, especially the press conferences and the news editions, was also highly confrontational, on purpose. By contrast, I got to collaborate with Orange County officials on producing their vaccine advocacy video because there were people there who were trying, in good faith, to save lives, and it was worth working with them. And in introducing the AMEND FAQ into prisons and our videos recorded by formerly incarcerated folks, we sought to work around CDCR to raise vaccine literacy behind bars by providing sources that our friends and neighbors inside could completely trust–thus working around CDCR (and, to be honest, counting on smuggled cellphones to do the work.)

In order to draw more careful lessons about how I’m going to do advocacy in the future, I need more complete information on which of these strategies worked and which didn’t – and why. For now, I’m providing some help in the form of a wonderful partnership with the Covid in-Custody Project, spearheaded by the unfailingly superb Aparna Komarla (read her recent and worrisome stories on the Davis Vanguard COVID page.) From now on, this blog will host all the data collected by the Covid in-Custody Project at this link, where you can get information about CDCR as well as several jails. Look for a post on resident and staff vaccine rates soon.

My heart is still very much in this battle, even as my body, mind, and spirit needed a health reset–I’m not constantly on twitter or facebook but I still care very much about what’s going on and am figuring out ways in which I can be optimally useful in this fight. In the meantime, if you swim at a city pool, in the name of all that is holy, please let faster swimmers pass you at the wall.

No comment yet, add your voice below!