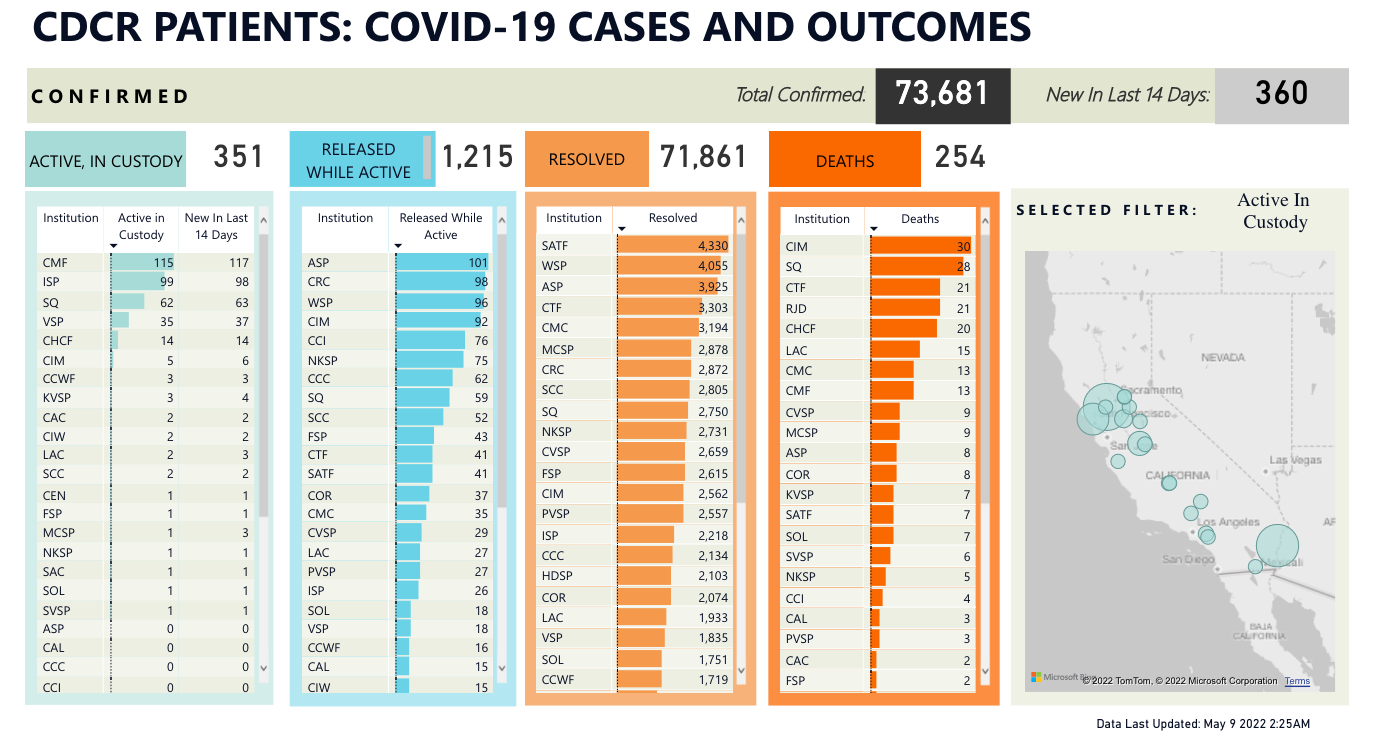

Lest anyone think that the COVID scourge is gone from California prisons, this morning’s ticker shows 351 active cases, 62 of which are at San Quentin. There are also, at the moment, 261 active cases among employees.

My coauthor Chad Goerzen has created a model of prison-community transmissivity, the basic features of which we will present in a future post here in the blog and in our forthcoming UC Press book Fester. For now, I can share that we are able to point to a number of deaths in the community (counties neighboring CDCR facilities) that we can causally attribute to the prison outbreak. Our efforts support and bolster a prior nationwide report by the Prison Policy Initiative (authored by Gregory Hooks and Wendy Sawyer) to a similar effect, though our model, which is local, can show direct causality and geographical ties. This is important to us because of the misguided zero-sum mentality that accompanied much of the community thinking about COVID – a “better them than us” sentiment that reflects lack of basic understanding of how prisons work, how viruses work, and how both of these factors can affect the surrounding community.

In other news, Aparna Komarla of the COVID-19 in Custody Project reports a worrisome, but utterly unsurprising, issue: the Sacramento sheriff refuses to discuss vaccination rates among his staff:

The first health order was issued in July 2021 and requires surveillance testing for unvaccinated correctional officers. The second order was issued in August 2021 (latest amendment was in February 2022) and mandates vaccines and boosters for a small group of non-medical officers working in the jails’ healthcare settings (ex: staff working in jail clinics). If the sheriff’s office in Sacramento is implementing and monitoring compliance with these orders, a record of vaccinated and unvaccinated employees must exist. But they insisted in their responses that no such records were available.

Our most recent public records request for the staff vaccination rate, however, received a different response. We were told that the Sacramento sheriff’s office is implementing and complying with the CDPH’s July 2021 health order, but they would not release their vaccination rate as it violated the employees’ medical privacy rights.

“The Sheriff’s Office strongly values our employees’ privacy and is concerned with the risk of unlawful data collection regarding employee medical data,” read their response. They cited California Government Code 6254(c.) and 6255, which give public agencies the right to not release files that are an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.

Their response is egregious for two reasons. One, it contradicts their previous stance that no records of the staff vaccination rate are available. And two, since we asked for the vaccination rate of the entire office and not the vaccination status of each employee, no one’s privacy would have been compromised. An aggregated vaccination rate (ex: 60% of employees are fully vaccinated) reveals nothing about the identity of those who chose to or chose not to get vaccinated.

Further, if medical privacy was a legitimate barrier, then the sheriff’s offices in Alameda, Santa Clara and San Francisco counties would not have been able to provide their vaccination rates. The Sacramento Sheriff’s response is unreasonable to say the least, and it illuminates a pattern of evading data transparency despite their legal obligations.

To me, this is one more reminder of a principle I talk about in Bottleneck (soon to become chapter 4 of Fester): the ineffectual nature of whatever powers the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) can assert over sheriffs. In addition to the many examples I cite there of county sheriffs not reporting COVID data at all (especially before August 2020, when the BSCC issued a request, but quite significantly even after), Aparna Komarla and her staff reported that, even when things are going on in jails, there is no effort to help others learn from positive examples, and that, as late as January 2022, the Sacramento Sheriff was hiding case rates at his facility. It should be obvious why in jails, which are closer to the community and have a more transient and temporary population (more community transmissivity and less community solidarity) and lower population vaccine rates, the staff vaccination rates should be a source of serious concern.

It’s true that, with the new variants and with diminishing returns of protection from the vaccine and boosters, this is a problem that cannot effectively be fixed now: the damage is already done. But the resistance to disclose the information is telling because vaccine rates (reflecting attitudes toward vaccination) are also bellwethers of other sentiments among staff. I’ve already written elsewhere about the paucity of information about the political views of prison and jail staff, and about the question whether the antivax campaign in this population reflects just that–antivax sentiments–or something bigger, like Petri dishes of Trumpism, virulent antiestablishment sentiments, or complete political capture of custodial staff unions. I think it’s really important to know who exactly we are dealing with here, because these are people entrusted with the care of vulnerable populations who get no sympathy from the public and, consequently, there are few checks on their attitudes and behavior. If the sheriff won’t provide these checks, or report about the situation, no one else will be able to effectively ensure that people are punished according to the California Penal Code and not according to the COVID-denialist whims of the guards.

No comment yet, add your voice below!