A few days ago I drew your attention to the upcoming election to the Israel Bar and, particularly, to the thoroughly corrupt candidate who had sex with women in exchange for guaranteeing their appointment to the judiciary. The crippling shame of having someone like that at the top of the administration’s licensing profession in itself should be enough for lawyers of all political stripes to vote him out. But yesterday I had an opportunity to think about the wider political ramifications of this election, when former politician Ophir Pines-Paz spoke at the democracy protest in Kiriat Tivon.

My parents were both deeply involved in the struggle for democracy and against corruption in Israel, opposing the occupation, religious coercion, social and financial inequalities, and the crimes and excesses of Netanyahu, his family members, and his government. During Netanyahu’s previous government, they protested weekly in front of his house. When this horrendous government took office, my parents faithfully reported to the protests each week. Sometimes, my dad would protest mid-week at an intersection, waving his big flag in hand. Today I felt called to take his place, as his kind, hugging, righteous arm let go of his flag for the last time last week. I took my dad’s flag and went to the protest, alongside a dear friend and thousands of attendees (the above picture does not do justice to the amazing sights and sounds.)

Anyway, as Pines spoke to the protesters and explained the importance of the bar election, I realized that the Israeli system might be opaque to English-reading audiences, and the scandalous possibilities of this election are too complicated, perhaps, for the American press to pick up. So here’s your primer:

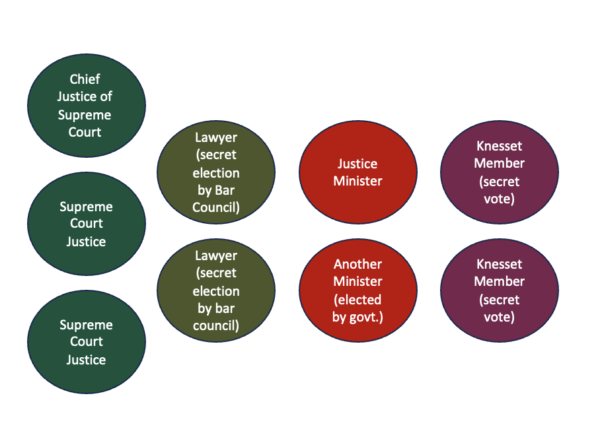

Israel does not hold judicial elections, as in U.S. states, nor does it hold purely political hearings by the legislature for its Supreme Court Justices as in the U.S. federal system. All judges in Israel are appointed by the President of Israel following the recommendation of a special committee, whose current structure, by law, is this:

The committee is designed to have an ostensibly professional majority: five lawyer/judge members and four politicians. Also, by custom, one of the elected Knesset Members is from the coalition and one from the opposition.

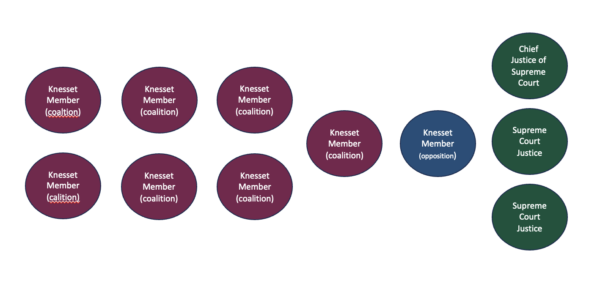

The proposed governmental “reform” would change the committee’s composition to look as follows:

Under this proposal, the committee would have eleven members, and judicial elections can be decided by a seven-member majority. In other words, if seven coalition members vote for a judge for political reasons, the sole opposition member and three judges cannot block them.

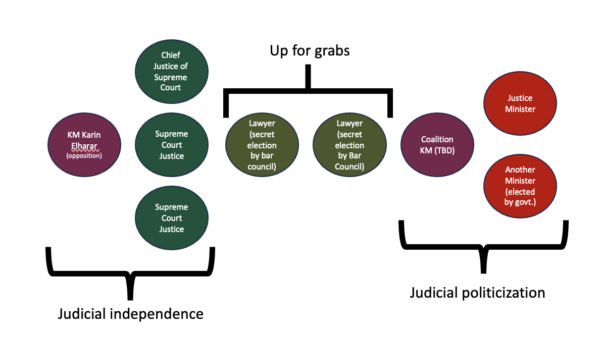

Thanks to dogged, relentless protests nationwide, the proposal has not passed yet. But the struggle to politicize the judiciary to guarantee that it favors the government continues on a variety of fronts. Two days ago, the government attempted to elect two coalition members (as opposed to one coalition member and one opposition member) to the committee. The vote was secret, and despite their efforts to drag things on and on and recount the votes for hours on end (how long does it take to electronically count 120 votes?) the Knesset elected only one member – KM Karin Elharar from the opposition. This means that at least four members of the coalition are secretly disgusted with Netanyahu and his governmental partners, though not brave enough to come out in opposition to their noxious plans.

What these noxious plans amount to is sitting government loyalists, ready to disenfranchise minorities, intensify the horrors of the occupation, and give free rein to the religious authority, in the Supreme Court, and more specifically, to block the appointment of a quiet, professional, independent judge by the name of Itzhak Amit to the Supreme Court. The coalition demonizes Amit and paints him as a post-Zionist demon. But in fact, he is widely respected as an excellent, hardworking, unassuming judge, and his sole sin apparently is that he decides cases based on the legal arguments, rather than by politics.

Can they do it? Let’s do the math:

With Elharar on the committee, and the three Supreme Court Justices presumably in favor of a strong, independent constitutional court, we have four votes for Amit and other independent judges. On the other side we have the two government ministers and the yet-to-be-elected coalition Knesset Member. The two votes up for grabs are those of the lawyers. Do you now understand why the government is so keen to seat Effie Naveh as the Israel Bar Chairperson? According to a recent exposé, Naveh’s campaign donors did so with the understanding that he will, in exchange, finagle a seat at the judicial election committee for them.

Now, Naveh has been consistently denying that he is beholden to the architects of the judicial reform. These vehement protestations are not particularly credible, given the efforts that the government is making to get him elected. But the bottom line is that Naveh’s personal or political opinions do not matter at all. He has been publicly exposed, and criminally convicted, as an unprincipled man, whose massive bribery and fraud operations are conducted to enrich him and his friends and to sexually gratify him. Is this the sort of person this government can do business with, as far as judicial appointments are concerned? You bet.

One of the challenges of the anti-government protests is that the insidious attack against the country’s democratic regime takes place on multiple fronts, including those hidden from sight. I hope this post shows how tinkering with each moving part of the judicial selection process can have vast consequences for democracy, and encourages those of you with an active Israel Bar membership to vote on Tuesday–and those of you with lawyer friends to encourage your buddies to vote Naveh out of office.

1 Comment

Very clearly explained! It does follow the general blueprint for de-democratization in places like Hungary and Poland, and also (at least over the past 15 years or so) in the US. It seems a good deal closer in Israel. I am not sure I would want the Bar to be able to decide something like this. All that said, I cannot imagine a judicial selection process that is anything other than political. Judges selected by the voters at large can be just as awful as those selected by political elites, even with systems that have effective functional representation for the legal profession. Wisconsin turned it around, though, so perhaps there is hope.