Yesterday, in my Modern Jewish Thought seminar, we covered the birth of Jewish denominations, starting with the establishment of the first reform community: the Hamburg Temple. Seeking to move away from what they saw as alienating, distasteful, or removed from their reality as German citizens aspiring to be emancipated, the founders of the new temple changed the liturgy: services would be held only on Saturdays and holidays and would include an organ and a choir. Men and women could sit together. Prayer would be conducted in German, not in Hebrew (then a dead language none of them could imagine would be revitalized). This revolution caused immense consternation, occasioning passionate commentary (all documented in primary sources you can find here), leading to a splintering of the community into what we now understand as orthodox, conservative, reform, and ultra-orthodox denominations.

The excitement of the people who initiated this new mode of prayer was palpable: they were creating a spiritual home in which they could be comfortable, of which they could be proud, to which they could invite their gentile friends. And yet, when we discussed this in class, my fellow students were deeply derisive. I could not understand why, so I asked, and as I suspected–my confusion reflected cultural ignorance. The other students explained that they experience reform Judaism as a namby-pamby, stodgy, assimilationist and flavorless Judaism. They also associated class snobbery with reform.

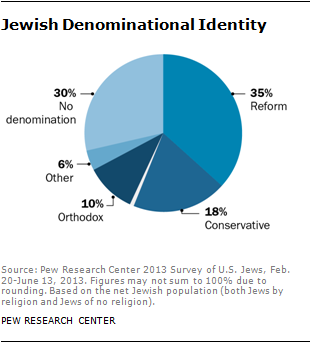

From a statistical perspective, their position makes sense. This descriptive analysis from Pew shows that, in the United States, reform is the largest Jewish denomination.

Eliminating the “no denomination” folks–there is a huge population of disengaged Jews in the United States, and we’ll talk about them in a different post–Reform encompasses the majority of practicing Jews. More than three times the number of Orthodox Jews. And the edgier, more “ethnic”, more mystical denominations–including Renewal and Reconstruction, which one sees a lot of here in the Bay Area–are quite minuscule by comparison (the data is from 2013, but I would be surprised if things changed much in the last decade).

Understanding the statistics is valuable, because in Israel, the picture of denomination is very different. For one thing, there is a state-sponsored religion: Orthodox Judaism, and now a particularly virulent, xenophobic, messianic version of it. Orthodoxy is the default for the entire Jewish life cycle because that’s what’s on offer by default: Just gave birth and in a fog of joy, postpartum depression, and/or overwhelm? the default is a big party in which a guy with a beard will cut off your son’s foreskin and everyone will enjoy the buffet. What are you going to eat? The accessible foods at your local supermarket are all kosher. In love? Congratulations! To have your wedding recognized by the state without taking a protracted bureaucratic journey, you marry orthodox. Registered as married? Only way out is a gett ceremony at the (Orthodox) rabbinate. Just lost a loved one and are too confused to come up with creative options? Orthodox men in black suits will mumble in Aramaic over your parent or spouse and then hold their palm out to the bereaved for a tip.

Other types of congregations exist and flourish in Israel, but they receive zero acknowledgment by the state apparatus, to the extent that even educated secular people don’t register their existence. Going to a reform service is a novelty. I remember how impressed I was one Yom Kippur when I attended the local reform congregation with a friend and saw that her whole family could sit together. I’m still in deep awe of Women of the Wall and female rabbis in Israel, both of whom are assailed. Had it not been for their heroic efforts, girls would not be able to have their bat mitzvah, complete with Torah reading, at the Western Wall (or anywhere else, for the matter.) It’s easy for my fellow students to deride these efforts in the same way that umpteenth-wave intersectional feminists deride first-wave feminists and forget they stand on the shoulders of the giants whose efforts granted them not only a voice, but a vote.

But this also reminded me that the idea of feeling “at home” “with my people” can be largely fiction if I assume that broader social trends do not influence what “my people” even means. We’re in an identitarian moment; splintering is happening all over the place, as is dumping on those not seen as edgy and interesting. Moreover, Jews tend to occupy an urban, educated, intellectual, bohemian place in American society and, in this milieu, accentuating any part of your identity that makes you “not white” is de rigeur. Since I, too, am a product of what’s happening around me, my own foray into Jewish Studies and the secular humanistic rabbinate comes from a sense that “my people”, whoever they are, need something enriching and affirming, something they can be proud of, as Israel implodes. I can try and put myself in the shoes of my 1818 ancestors, who probably felt the same way. A German churchlike venue is not what I have in mind when I think “comfort” and “feeling at home”, but they did–it’s what was around them at the time.

No comment yet, add your voice below!