(pictured above: architect Shari Mendes assisting military troops in handling female genocide victims.)

Prof. Malcolm Feeley, my legendary PhD supervisor and, for the last 25 years, my mentor, coauthor, and good friend, is one of the pioneering giants of the law and society field. He is universally admired and loved, and for good reason. Amidst the many characteristics that make him an outstanding researcher and thinker is his almost mythical ability to make sharp and revealing analogies across space and time. For example, in his amazingly creative address upon receiving the Paul Tappan prize, he compared convict transportation in the Early Modern era to electronic monitoring (I commented about it here). In his work on guilty pleas (Malcolm is the granddaddy of lower criminal court research) he made the paradigm-generating analogy between the prosecutor-driven generation of plea bargains to the transition from bazaars to supermarkets.

In an excellent opinion piece in The Hill, Prof. Feeley, who taught and researched at elite universities for fifty years (including a long stretch at Berkeley and respectable stints in academic administration, including as the President of the Law & Society Association and the Chair of the JSP program at Berkeley), draws on his formidable analogy powers to diagnose the reason for the stuttering university responses to the eruption of antisemitism on campus. It is a bitter, cutting analogy between the decisions faced by the university presidents and those faced by President Roosevelt during World War II not to save the Jews from the concentration camps. He explains:

Early in World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt learned of Nazi plans to systematically murder European Jews. Later, advisors urged him to order the bombing rail lines leading to Auschwitz. He rejected their pleas. Actions to prevent these murders, he responded, would turn the war into a campaign to save Jews, and in so doing undermine American’s support for the war.

And now?

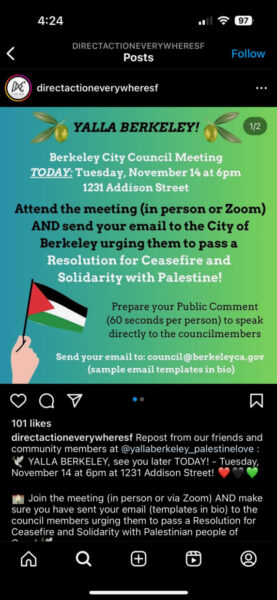

On Oct. 7, we witnessed the most deadly pogrom, excepting the Holocaust, against Jews in modern history, and thousands of people danced in the streets, not only in Beirut, Damascus, Baghdad, and Tehran, but also on campuses in Philadelphia, New York, Cambridge, Ithaca, and Berkeley. At the time, no university official on a major U.S. campus that I know of unequivocally denounced this action as a pogrom against Jews and excoriated their students and faculty for celebrating the occasion.

Two months later, on Dec. 5, presidents of three major universities at which celebrations of the pogroms took place — Harvard, MIT, and the University of Pennsylvania — were questioned at a hearing of the House Education and Workforce Committee. Their collective responses were even feebler than those issued immediately after the pogrom. When called upon to say that the calls for the support of the pogrom of Oct. 7 were antithetical to Harvard’s institutional values, President Claudine Gay could only say, “I personally oppose this,” and then parse the speech/action distinction, defend speech, and announce that Harvard had beefed up security for its Jewish students. Nowhere did she say such views had no place on Harvard’s campus, and that she was ashamed to have such students and faculty at Harvard. President Sally Kornbluth of MIT and President Elizabeth Magill of Penn, fared only slightly better. All reacted defensively. None showed moral clarity, or demonstrated leadership. All obfuscated. At best, they seemed managers trying to cope rather than inspired leaders of noble institutions. At these universities, where almost all the students receive A’s, these educators failed.

This is not because they are anti-Semites or embrace the cause of Hamas. Rather, I think it is because they face the FDR dilemma: If they single out, and in no uncertain terms condemn, anti-Semites on their campuses, they run the risk of alienating a significant portion of the social justice constituency that they have helped to create and in part to whom they owe their positions.

You should read the piece in its entirety.

Malcolm also includes a factual tidbit I was unaware adds a piece of information that I didn’t know, but which doesn’t surprise me: a colleague of ours hired a survey firm to do a poll at Berkeley, and it turns out that 53% of the students enthusiastically shouting “from the river to the sea”–folks enrolled at the best public university in the United States–don’t know which river and which sea, along with much other breathtaking ignorance.

I deeply and fervently hope that the many thousands of academics around the world who admire and respect Malcolm will take the time to read his opinion piece and consider where they stand vis-á-vis the poison on campus. I also hope that they read the heartbreaking article in the New York Times about the horrific and systematic rapes perpetuated by Hamas terrorists during the October 7 massacre.