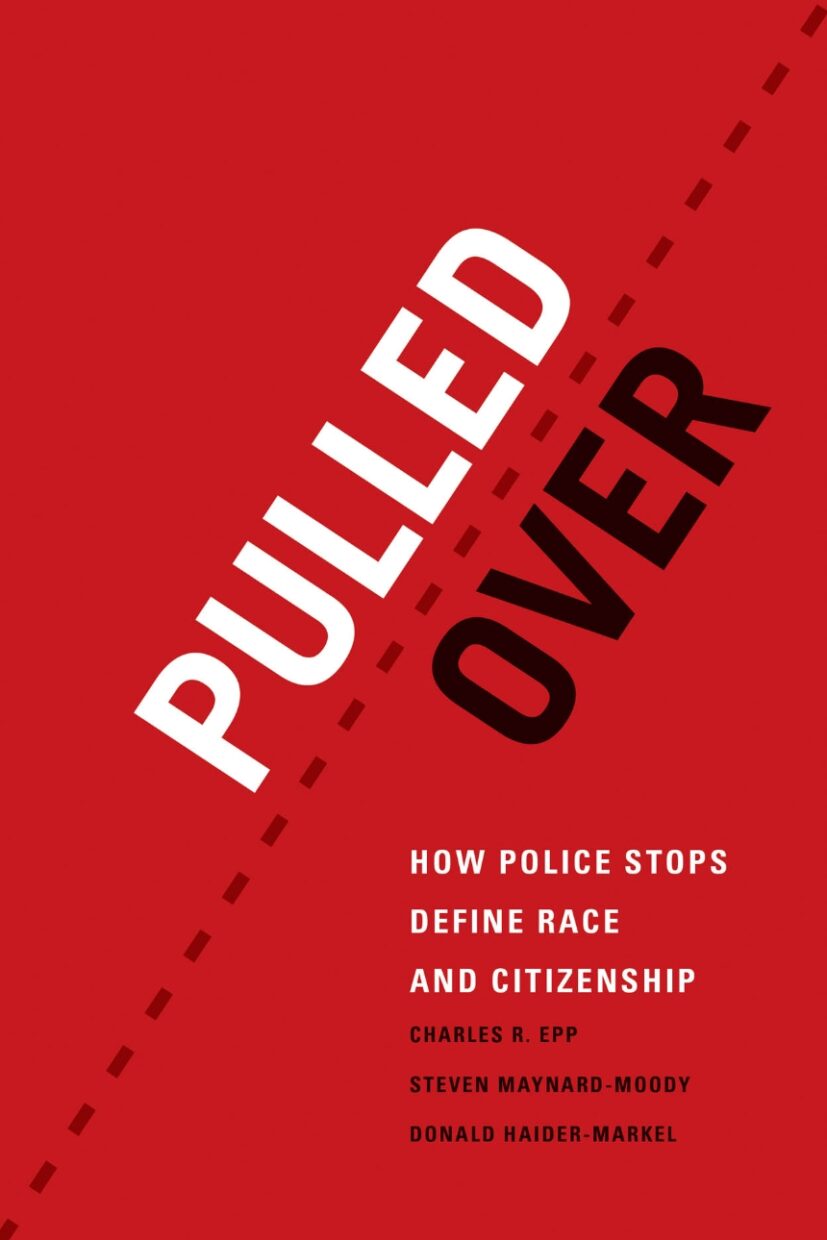

In 2014, Chuck Epp, Steve Maynard-Moody and Don Haider-Markel published their wonderful book Pulled Over. The book is based on a survey of, and follow-up interviews with, more than 2,000 drivers in the tri-state Kansas City metropolitan area, about their experiences being stopped on the road. They learned important things about how the police use routine stops for trifling traffic offenses as fishing expeditions for other possible crimes.

The legal background is as follows: in order to search someone’s car, the police need probable cause that evidence of crime is in the car. The scope of the search has to follow the probable cause (e.g., if there is probable cause that the driver stole a baby elephant from the zoo, there is no permission to search the glove compartment.) Traffic offenses, with the notable exception of a DWI, do not usually encompass the possibility that there is something inside the car related to the offense. Therefore, suspicion of a traffic offense–even when the officer sees it happen–does not manufacture enough justification to search the inside of the car beyond a cursory inspection for weapons. It certainly does not permit the police to open containers within the car, where drugs might be found.

But a traffic offense does manufacture enough justification to conduct a quick stop of the car, and things can develop from there. While interacting with the driver, the officer might give the car a cursory look, to see if anything stands out; the officer might walk a narcotics dog around the vehicle; the officer might ask some questions (“where do you live?” “where are you going?”) to see if any further suspicion develops; and, most importantly, the officer might ask the driver for consent to search the car, which will grant permission for the search even if individualized suspicion is not present.

This, of course, creates a tempting incentive for police officers to stop vehicles for trifling traffic offenses, especially when they have a hunch (and no more than a hunch) that the driver is mixed up in something more serious. At worst, they haven’t broken the law; no harm, no foul. At best, the interaction during the stop could mushroom into justification to search the car, which might yield something. You might think that courts should inquire into whether the traffic violation was no more than a pretext for the stop, but courts do their very best to stop short of such inquiry. In Whren v. U.S. (1996), the Supreme Court held that inquiries into the subjective state of mind of police officers are out of bounds, and that the Fourth Amendment’s requirements are satisfied once there is an objective justification for the stop, no matter how trifling the offense is. Courts in some states, like Washington, have held such stops unlawful based on their state constitution–but even if you’re fortunate to live in such a state, you have to have solid proof that the stop was pretextual.

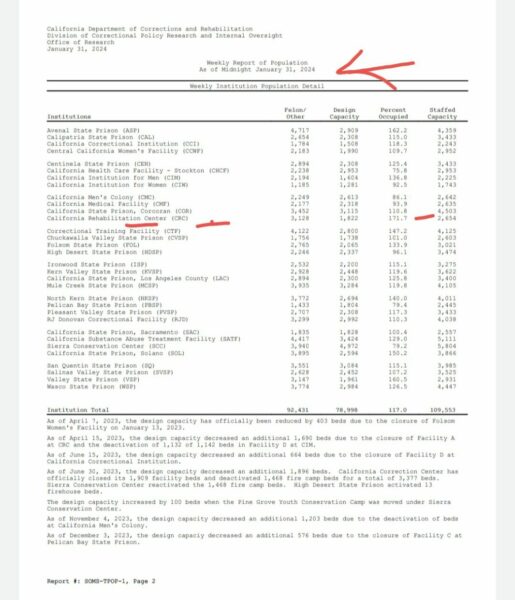

The problem is likely obvious to readers: without concrete evidence of, say, racial profiling based on how a driver looks or what kind of car they drive, which will be present only in rare cases, cops routinely lie on the stand that they have genuine and pressing concerns and a passion for traffic enforcement, and courts routinely maintain the pretense that these stops are earnest and genuine, which presumably holds up the legitimacy of the system. Pulled Over confirms that this indeed happens on a systematic level. Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel found that drivers experience two different kinds of stops: traffic stops for legitimate offenses (“do you know why I stopped you?”) that end in a citation or a warning, and investigative stops (for things as minor as a broken taillight) that then lead to inquiries and fishing expeditions and end, at best, with a bitter, cynical, humiliated driver and at worst, if things escalate, in an arrest.

California is now trying a solution to this problem. Following reforms approved by police commissions in San Francisco and Los Angeles, the California legislature has enacted Senate Bill 50, which you can read verbatim here. The idea is this:

This bill would prohibit a peace officer from stopping or detaining the operator of a motor vehicle or bicycle for a low-level infraction, as defined, unless a separate, independent basis for a stop exists or more than one low-level infraction is observed. The bill would state that a violation of these provisions is not grounds for a defendant to move for return of property or to suppress evidence. The bill would authorize a peace officer who does not have grounds to stop a vehicle or bicycle, but can determine the identity of the owner, to send a citation or warning letter to the owner.

The bill would authorize local authorities to enforce a nonmoving or equipment violation of the Vehicle Code through government employees who are not peace officers.

I remember the jeremiads on Nextdoor when this was first proposed in San Francisco. The concern was that the city would completely give up on traffic enforcement, resulting in accidents and victims. As a two-wheeled vehicle rider (first a motorcycle and now a cargo e-bike) I’m very sensitive to traffic enforcement concerns. But it looks like the worries are overblown, because the low level offense list in the bill is as follows:

(A) A violation related to the registration of a vehicle or vehicle equipment in Sections 4000 and 5352.

(B) A violation related to the positioning or number of license plates when the rear license plate is clearly displayed, in Sections 5200, 5201, and 5204.

(C) A violation related to vehicle lighting equipment not illuminating, if the violation is limited to a single brake light, headlight, rear license plate, or running light, or a single bulb in a larger light of the same, in Sections 24252, 24400, 24600, 24601, and 24603.

(D) A violation related to vehicle bumper equipment in Section 28071.

(E) A violation related to bicycle equipment or operation in Sections 21201 and 21212.

Since the police can capture these minor violations through filming equipment and send citations to people, the bill strikes a good balance between traffic safety and civil rights preservation. It also reflects a clear-eyed perspective on the protean quality of race stops. Efforts to legislate against pretexts, as such, are bound to fail, as police departments will respond by getting cops to testify better on the stand about the reasons for the stops. Efforts to dig up evidence of pretexts via departmental emails will do no more than push these policies underground, into Snapchat and the like. But this effort curtails the use of minor traffic offenses at the root, by preventing these stops in the first place.

I’ve been trying to think how police officers might subvert the bill’s purpose, and the only loophole I can find is this: the bill does allow the stop if “there is a separate, independent basis to initiate the stop or more than one low-level infraction is observed.” We will have reduced the number of fishing expeditions originating with, say, a broken taillight, but such stops will still happen if, say, two of these minor traffic offenses are observed. I

I really hope that someone is doing evaluative research on this. If so, and if someone’s testing this using a survey instrument similar to the one in Pulled Over, the questions I’d be interested in are:

- Has the overall number of traffic stops declined?

- Has the racial composition of stopped drivers changed?

- Has the make and appearance of stopped cars changed?

- How many stops now begin with the cop asking the driver, “Do you know why I stopped you?”

- How many stops now result in car searches?

- How many stops now result in the arrest of the driver? In any violent incident between the cop and the driver?

If any readers are aware of a study currently being conducted, please let me know in the comments.