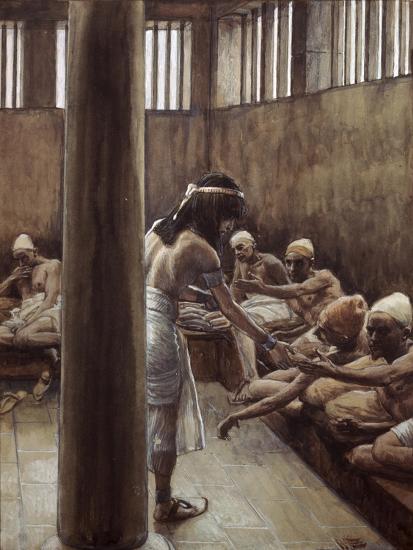

In the last few weeks I’ve been sharing snippets from my new book in progress, Behind Ancient Bars. Chapter 2 of the book will be devoted to the Hebrew Bible’s most illustrious prisoner, Joseph. You can find the full story in Genesis 39-41. Briefly, Joseph is thrown in prison following a false rape accusation by the wife of Potiphar, to whom Joseph had been sold as a servant. The biblical story offers us a rather rich account of Joseph’s carceral experience, including his responsible role in prison management while a prisoner himself and his interaction with two fellow inmates (the chief cupbearer and the chief baker). We also learn of his unsuccessful efforts to have the chief cupbearer curry favor for him with Pharaoh and of his eventual release, and auspicious rise, when his dream interpretation skills are needed.

Medieval midrashists found Joseph a fascinating subject, but tended to focus on his dreams, the salacious story with Potiphar’s wife, and Joseph’s later reconciliation with the brothers who sold him to the Ishmaelites. But one also finds quite a bit about his prison journey there, and the expanded stories tend to adhere to two important messages. The first is a concerted effort to frame the entire incarceration journey—in terms of time as in terms of content—as orchestrated by God for specific purposes, suggesting God’s interest not only in the people of Israel but also in geopolitical matters. I see examples of this in other biblical incarceration stories, but it is especially pronounced here. Second, and relatedly, there is an idea I’ve already discussed in the context of Daniel, Esther, and Jeremiah: the notion that Joseph undergoes a penological transformation within confinement that prepares him for his prophetic leadership after reentering Egyptian society.

I’ve recently come across Nicholas Reid’s excellent book Prisons in Ancient Mesopotamia. In his analysis of primary sources, Reid urges us to use a wide lens when discussing prisons in antiquity, similar to what we now do in modern incarceration studies. He says this, with which I’m wholeheartedly in agreement:

When thinking of a history of prisons and imprisonment, one must look beyond the stated goals and stated functions of the prison to the actual practice. . . since prisons are multifunctional, the historical investigation into imprisonment should not revolve solely around the question of punishment. . . the adaptability of limiting corporal movement through imprisonment to meet numerous social goals and handle numerous social ‘problems’ has deep roots in history, even though direct connections and linear developments do not exist.

Even though Joseph was not sentenced to a prescribed period behind bars, and even though biblical punishment is usually retributive in nature, there is enough in the biblical descriptions and the midrashim to point to a message eerily similar to the one parroted in rehabilitation programs and parole hearings today: that incarceration is a “rock bottom” point in a prisoner’s journey that is an essential part of his or her coherent life story, that one goes down in order to go up, and that one develops important prosocial and other skills in confinement that set him or her up for a pivotal historical role postincarceration. In light of this, I decided to rewrite the Joseph story as a parole hearing transcript, relying heavily on the medieval midrashim. Here’s a short snippet:

PHARAOH: Okay, since we’ve moved to the inmate’s C-file, let’s see how he did in prison. From what I see from the record, you haven’t had many visitors in the twelve years you’ve been inside.

JOSEPH: No, Your Majesty. I believe only in the early days, when Zulycah still visited me.

AMHOST: I’m not sure I understand: The woman whom you claim falsely accused you of rape visited you in prison?

POTIPHAR: Your Priestly Eminence, since I oversee the prison, she can come and go as she pleases, and she even helps me with the logistics.

PHARAOH: And when she visited you, what did you talk about?

JOSEPH: She was trying to persuade me to give in to her. You know, “How long wilt thou remain in this house? do but listen unto my voice, and I will release thee from thy prison.” Like that. I had to keep saying: It is better for me to remain in this house, than to listen unto thy words, and transgress against God.[1]

AMHOST: I guess we keep things nice and cushy for you in Thebes. Some people would easily mistake you for a prison administrator, rather than an actual prisoner, and think Potiphar just moved you to another job to put some distance between you and his wife.[2]

MERITAMUM: It’s not like that, Your Grace. The write-up about the visit documents that the inmate was repeatedly threatened by his accuser. She was overheard saying, “if thou wilt not do my wishes, I will put out thine eyes, and I will put additional chains upon thy feet, and I will surrender thee into the hands of such as thou hast not known, neither yesterday nor day before yesterday.”

HAT: Looks like it was even worse. I have the 128 write-up that she put in his file, and it says that, while they were setting the table at chow hall, cleaning the drinking glasses and all that, she would say to him: ‘In this matter, I mistreated [ashaktikha] you. As you live, I will mistreat you regarding other matters.’

MERITARIUM: Oh, but he gave as good as he got. Basically played her at her own game. Like she said “ashaktikha,” so he would say to her: ‘[God] “Performs justice for the oppressed [laashukim].”’ (Psalms 146:7) [She would say:] ‘I will reduce your sustenance.’ He would say to her: ‘[God] “Provides food for the hungry.”’ (Psalms 146:7) [She would say:] ‘I will shackle you.’ He would say to her: ‘“The Lord frees the imprisoned.”’ (Psalms 146:7) [She would say:] ‘I will cause you to be bent over.’ He would say to her: ‘“The Lord straightens the bent.”’ (Psalms 146:8) [She would say:] ‘I will blind your eyes.’ He would say to her: ‘“The Lord opens the eyes of the blind.”’ (Psalms 146:8)[3]

PHARAOH: Dear Maat. How far did all of this go?

MERITARIUM: We’re not entirely sure, because there’s a lot of hearsay in prison intelligence. Rav Huna said in the name of Rabbi Aḥa, you know, that sort of thing. But rumor was that she placed an iron bar beneath his neck until he would direct his glance toward her and look at her. Nevertheless, he would not look at her. That is what is written: “They tortured his legs with chains; his body was placed in iron.” (Psalms 105:18)[4]

PHARAOH: Nice facility you run there, Potiphar.

POTIPHAR: I can’t possibly screen my own wife from the list of visitors, Your Majesty.

PHARAOH: Why would you let her do it? Did you think he was guilty?

POTIPHAR: Oh, no, I knew he was innocent. Even my kids knew.

PHARAOH: What?

POTIPHAR: We all knew. My kid kept saying, “stop beating on him, my mom is lying.”[5] Even on the way in, when I was booking him, I said to him, “Joseph, I know you didn’t do this, but I’m locking you up so I will not attach stigma to my children.”[6]

MERITAMUM: And even so, Your Majesty, when she visited him in prison, it didn’t seem to faze the Inmate. He was overheard replying, hold on, it’s hard to read the hieroglyphs, “Behold the God of all the earth, he is able to deliver me from all that thou wouldst do unto me. For he giveth sight to the blind and he freeth the captives and he preserveth the strangers that are in the land they never knew.” Eventually she gave up and stopped coming.

PHARAOH: Do we have any laudatory chronos in the file?

MERITAMUM: Yes, Your Majesty. The inmate was charged, de facto, with the functioning of the entire administration.

PHARAOH: You entrusted. The entire prison administration. To a prisoner.

POTIPHAR: The whole thing. Eating, drinking, binding people, releasing them, torturing them, giving them a rest. He would call the whole thing and whatever he said, went.[7]

HAT: It says in this chrono, “the minister did not have to see anything he put in the inmate’s hand.” I’m not sure what this means.

POTIPHAR: It means I didn’t have to supervise him, because God helped him succeed in prison as well as on the outside. It’s a kal vahomer.

HAT: A what?

POTIPHAR: A kal vahomer. Argument a fortiori. They have to say he was successful in prison, because success on the outside would be self-evident.[8]

HAT: See, I read it differently. I read it that you didn’t see anything fishy or poorly performed.[9]

POTIPHAR: You know these prison write-ups. You can read them seventy different ways.

HAT: Mr. Jacobson, do you feel that you were treated fairly in prison?

JOSEPH: To be honest, I did end up feeling relieved. Back home, whenever we ate, my father would give me the choice portions, and I always had to look over my shoulder lest my brothers take revenge. And I confess that here in prison I could breathe a bit easier. But God likes to give me a challenge, so I figure he’ll sic a bear on me anytime soon.[10]

HAT: Not sure I understand what the bear’s got to do with any of this.

JOSEPH: It’s got to do with the grain.

AMHOST: What grain?

JOSEPH: You’ll see.

[1] Sefer HaYashar (midrash), Book of Genesis, Vayeshev 19

[2] McKay (2009).

[3] Bereshit Rabbah 87: 10.

[4] Bereshit Rabbah 87: 10.

[5] Sefer HaYashar (midrash), Book of Genesis, Vayeshev 18-19

[6] Bereshit Rabbah 87: 9.

[7] Midrash Sekhel Tov, Bereshit 39:22:2

[8] Bereshit Rabbah 87:10; Midrash Sekhel Tov, Genesis 39:23:3.

[9] Midrash Sekhel Tov, Bereshit 39:23:2

[10] Midrash Sekhel Tov, Bereshit 39:23:4