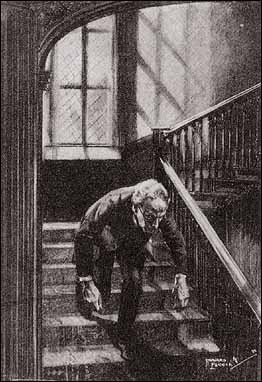

One of the creepier, more Gothic stories in the Sherlock Holmes canon is The Adventure of the Creeping Man, in which Holmes and Watson are retained by the secretary of an academic, Professor Presbury, when the professor begins to behave in a peculiar and alarming manner. Recently engaged to a woman much younger than himself, the professor becomes irascible and menacing and his body language is altered: he climbs and creeps like a monkey, at some point climbing up to his daughter’s window. In addition, the professor is very secretive about packages he receives from Europe, and his own dog begins to attack him.

Skip this paragraph if you want to avoid spoilers (but I hope you won’t, because otherwise the rest of this post won’t make much sense): Holmes figures out that the professor’s behavior is cyclical–he seems to be taking some behavior-altering substance every nine days. It turns out that he sought suspicious rejuvenating treatments from a shady European practitioner (one in a long line of shady antagonists from the continent in the canon) in anticipation of his future nuptials to the young woman.

I’ve probably read this story dozens of times, alongside the rest of the canon, and like any person who has a decades-long loving relationship with an artistic or literary work, it hits me different each time. In her gorgeous book The Jane Austen Remedy, octogenarian author and literary scholar Ruth Wilson tells of her evolving understanding and relating to Austin’s novels, which she has been reading and rereading since 1947. I have the same sort of relationship with Arthur Conan Doyle. His works enrich and educate me, and sometimes piss me off, in ways that evolve throughout my life. I just recently rediscovered the terrific, chilling film adaptation of Lot no. 249 and my life hasn’t quite been the same since I saw it. But I digress–let’s get back to Professor Presbury and his mysterious medication.

Earlier in my life I found Presbury pitiful and creepy in equal measures, and as a modern reader, identified with the deep distaste that Presbury’s daughter Edith and his secretary, Bennett, have for the huge age gap between Presbury and his fiancée. It’s easy to mercilessly dismiss Presbury as a pathetic old man, desperately attempting the impossible: to bend evolution to his will using the Victorian version of Viagra so as to turn back the wheel of time. But when I started studying criminology and learned of the emergence of positivism, a lot of this stuff made more sense to me. As I have explained elsewhere, Doyle started writing the stories when Darwinism was already a sensation in England, and his enthusiasm about the marriage of science and crime is palpable in the stories. Shortly before Doyle began writing, Italian doctor and academic Cesare Lombroso published his book L’Uomo Delinquente, in which he argued that criminals were atavists, evolutionary aberrations, who could be identified by physical markers such as their measurements and facial features. If you visit Museo Lombroso in Turin, an experience I highly recommend, you’ll get more of a sense of the life and times of Lombroso, as well as of the sociopolitical underpinnings of his theory, and you’ll see his huge collections of skeletons, skulls, and death masks of criminals. You can also read David Horn’s fantastic book about Lombroso. This also explains why Holmes offers such aggressive censure of Presbury toward the end of the story, when all is revealed: “When one tries to rise above Nature one is liable to fall below it. The highest type of man may revert to the animal if he leaves the straight road of destiny.” To subvert the natural course of events by injecting one with the extract of monkey glands is to reverse the ape-to-human evolution. It is an aberration, it is recurrence to atavism, and it must not be attempted.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Professor Presbury lately because of my own physical predicament. Normally I have heaps of distaste for tiresome, self-centered Internet confessionals crafted to “raise awareness” to the suffering and misery of the author, so of course I ask your forgiveness in advance for burdening you with more of this annoying genre, but this is such an unspoken issue that it can benefit from some exposure. I’m in perimenopause and in the thick of an entire buffet of horrible symptoms. It is difficult to describe the bad feeling to anyone who is not experiencing it. Everything you’ve read about–the brain fog, the weight gain, the irritability, the heart palpitations, the sudden drop in aerobic capacity, the frequent and unpredictable periods, the hot flashes and night sweats–is true, of course, but underlying it all is a deep, unrelenting feeling of malaise beyond definition, that makes one want to crawl out of one’s own skin and flee far, far away. I’ve tried to remind myself that this could also be a product of my grief over my father and the appalling antisemitic climate I experienced this year, but the physical suffering cannot be denied and it is immense. I’m not a crybaby, I’ve swum marathons in frigid water without complaint, but perimenopause has truly brought me to my knees, and shortly before my 50th birthday I found myself asking my doctor for HRT.

Hormone replacement therapy takes a different form for each woman. In my case, it involves 12 days a month of progesterone, taken orally in enormous capsules, and estrogen patches that are supposed to be waterproof but don’t fare 100% well if one swims a strenuous workout. Anyway, we’re a month in, and the sense of relief is palpable. I feel alive. I have my life back. My period was short and predictable. No more sweating, no more weeping, mental clarity is back, and my lifting and swimming have both improved.

I’m mentioning this because I sense there is still some stigma attached to taking hormones. For one thing, it presents one with one’s Professor Presbury-ness: I’m now older, I miss being younger, I’m pathetically trying to bring back my juice by taking hormones my body no longer reliably produces. It’s embarrassing and humbling and, oddly, has brought about a wave of sympathy for Presbury (and for another pathetic and scary heroine of a book I read in childhood, She by Henry Rider Haggard.) I get it now. I get no longer recognizing your vessel and longing for the sense of vitality you’d taken for granted. Watching (and being enthralled by) the Olympics certainly drove the point home. I am captivated and inspired by the athletes and their stories. Like so many people worldwide, I was swept into the drama, joy, camaraderie, and astonishing performance of the USA Men’s Artistic Gymnastics team and their heroic capturing of the bronze medal. I could daydream about performing astonishing feats of strength, endurance, and agility on the international stage, but I’m not an insanely talented kid in his or her early twenties who spent hours at the gym every day of their life; instead, I’m a middle-aged family woman and where I am in life is a lot more reminiscent of the athletes’ parents, shown cheering for them in the audience. But the joy on the faces accomplishing their incredible athletic goals made me also crave the sense of feeling strong, capable, confident in my body, the way I felt a decade ago when I was swimming open water marathons. HRT has brought this sensation back. I feel at peace inside my vessel. It is much easier to be an Instrument of God’s Peace, as per the Prayer of St. Francis, when your body works in predictable and satisfying ways.

There’s also the health stuff: many women are still terrified of HRT because of misleading science, which made many friends of mine who are now in their sixties miss out on a medically provable, low-risk solution to abject physical misery. If you follow only one link in this blog post, make sure it’s this superb, science-based NYT exposé of how women have been cheated out of this important remedy (you’ve read thousands of screeds about misogyny in medicine, so insert one here). Risks of cancer with HRT are associated only with start of use after one turns 60. Start using hormones before you’re 60, and the benefits often outweigh the risks.

Finally, there’s this notion that we must accept what is happening naturally and resort to herbal remedies and meditation. HRT, we are warned, will not do the trick if we are too lazy to eat well, exercise, and reduce stress. I find this message patronizing and insulting, not only to me, but to many women in the same condition. I eat extremely healthy, plant-based, and maximize lean protein and fiber beyond what doctors and coaches prescribe active people. I work out approximately 90 minutes a day, combining strength and cardio, I lift heavy, I do plyo, I do intervals and sprints in the pool, I do pilates and abs and conditioning, I stretch, and I commute by bicycle. “Reducing stress” as a prescription for women with kids and aging parents and mounting responsibilities at work and elsewhere is a risible proposition, but I’m a meditation teacher, I do engage in contemplative practices and know how to do it. Why try to sell me on black cohosh and St. John’s Wort rather than on the hormones my body has produced naturally for decades–estrogen and progesterone–and give women who resort to the latter the sense that they have somehow failed to take proper control of their health? I’ve spoken to several friends who have started taking HRT. It’s not an openly talked about issue, which, lemme tell ya, is a damn shame, because there is a wealth of information in these stories. For one thing, the hormonal dosage and delivery method do require attention and, frequently, tweaking along the way. But every single woman I talked to has raved about the vast improvement to her quality of life taking hormones. Why not take them? Do some investigating, talk to your doctor, and take your life back. Feeling comfortable in your own skin is your birthright.

Oh, and please read Stacy Sims’ excellent book Next Level, which is a phenomenal primer on menopause and perimenopause physiology for active women, accompanied by superb action items and recommendations, or take her fantastic menopause online course. This is happening in your body right now. You’re living it. You’re not in the waiting room, holding out for something better. This is your one and only body, your one and only precious life. I’m rooting for you to improve it, to seize it by the horns. Kind of like Professor Presbury tried to do, but science-based and practical. Not on the sly, not in the shadows. In the open, so that we can all talk about this and make the best medical decisions for ourselves.