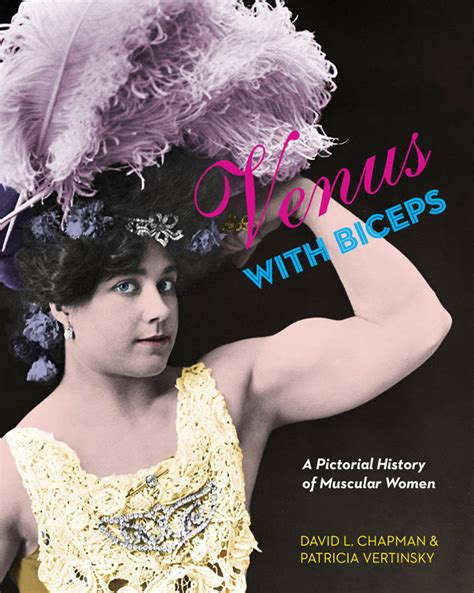

I’m a month and a half out from the beginning of my HRT journey and it’s a good time to review my health and fitness scenario. Many reasons to despair of the world, but I’m trying to keep as upbeat as I can through it by pursuing sources of inspiration. One of these is David Chapman and Patricia Vertinsky’s fabulous book Venus with Biceps, which offers a 200-year history of muscular women and strongwomen and their exploits through art and photography. Another has been the marvelous Team USA Gymnastics; my family and I went to see the Gold Over America Tour last night and marvel at the feats of athleticism and grace.

My personal favorite in this astounding group is Brody Malone, whose miraculous comeback from a horrific knee injury in time to be a massive contributor to the MAG USA team’s heroic bronze medal was an incredible tour de force of spiritual fortitude, discipline and grit. I’ve had to come back from far smaller setbacks–shoulder tendon things, broken toes, and sprained ankles–the latter only four months before I ran the Oakland Marathon, and remember well how grueling that was, so I am filled with awe. There are a lot of other reasons why I admire this guy so much–in the current, aggressively polarized state of this nation, it’s no small thing for a guy from a small town in Georgia to spend formative college years at Stanford and handle the culture clash with such grace (Brody, if you’re reading this, I would love to meet you! You and your family are welcome in my home anytime, and also, we need to have a conversation about animal rights). But everyone else in this group is phenomenal as well, and we had a wonderful time reveling in the breathtaking routines and delightful choreography of the whole thing.

It’s to the credit of the new HRT regime, as well as some newfound room to breathe while on research leave, that I owe what seems to be an upswing in my fitness. I’m improving in the weight room in ways that surprise me–not only in adding weights and reps, but also in being humble sometimes and staying with the same weights until I see better form. My benching and squatting have improved and I’ve noticed that my deadlifting gets a huge boost from listening to cheesy encouraging music when I add plates. I’ve also thrown in some olympic weightlifting sets on occasion, inspired by the remarkable Olivia Reeves. Really grateful to coaches Karina Inkster and Zoe Peled for their no-BS advice and coaching in the weight room and in the kitchen.

Things are looking up in the swimming pool as well, and although I’m treating this as the beginning of a comeback, I’m not yet sure what I’m coming back to. Maybe other parents of young children manage to somehow weave marathon swimming and training into their day, but our rhythm at home will not come close to allow me to spend the kind of time in the pool that I did when I trained for Tampa, the Sea of Galilee, or even something shorter like the Thames Marathon. Technique takes one only so far, and for serious marathoning one has to swim big volumes, and those take time. So maybe I’m looking at racing only within the 6-to-10-mile range. I’m not sure yet.

There’s one thing I’m doing better than when I was racing, and that’s cross training. I was, and still largely am, a disciple of Terry Laughlin and Total Immersion, and a big part of that was swimming races and long sets with a very slight two-beat-kick. The idea was to keep the quads, which eat up a lot of oxygen, for later, but “later” never seemed to come, and I don’t think I ever learned to kick properly. The difference is that I used to spend all my workout time in the pool, whereas now I spend half of it at the gym. Putting in the effort to build leg muscles in the gym is paying off in the sense that I have muscles I can now recruit, and this is going to be what I rely on to bring my times in the pool back to where they were. I still have several months of work to shave some seconds and minutes off my time, but I’m already seeing some times that I wasn’t expecting, so this addition of a small and fast six-beat-kick is already paying off in the second half of each interval. I’m still benefitting a lot from the months I spent working with coach Celeste St. Pierre on this and from her sage advice on stroke refinement and on midlife in general.

To give you an idea of what things look like these days, here’s an overview of my week. I’m now doing some form of cardio and some form of strength almost every day, and the combination seems to work well. Things do change some from week to week, because pool and gym proximity can be an issue and OW is getting cold (I’m more of a wuss than I used to be). Thankfully, San Francisco has lots of fantastic stairways, and choosing a different one every week to do some repeats is fun.

| Monday | Lower body lift | Swim (with pull drills, short intervals) or stairs, or hills |

| Tuesday | Upper body lift | Swim (with kick drills, short intervals) |

| Wednesday | Abs | Plyo + trampoline |

| Thursday | Lower body lift | Swim (more short axis) |

| Friday | Upper body lift | Krav Maga (sometimes also swim) |

| Saturday | Pilates + mobility | Swim (OW or short) or stairs |

| Sunday | mobility + foam rolling | leisurely morning walk |

Add to this the fact that I commute by e-bike, and I think it’s a pretty active week for someone who turns 50 in November and is just beginning to find a way out of the perimenopausal woods of woe. The key is to schedule this around research and family; I want to finish the biblical prison book in a few weeks, and I also want to be a present and energetic parent. The time expenditure is not trivial; we’re talking about 90 mins of physical activity not including the bike commute, so at least some of it has to happen before my kid wakes up and some of it while he’s in school. In general, this calls for more productivity and less dawdling in the library and in the classroom, and I find that the HRT bought me some mental clarity that helps with that.

As far as food goes, I try to hit 100g of protein a day, which requires some aggressive strategizing when it’s plant-based. I usually succeed if I start the day with 30-40 grams right out of the gate, which require some combination of tofu/tempeh, high protein vegan yogurt, and/or protein powder. The easiest thing to get this to happen is with a giant protein smoothie, full of fruit and greens; it’s not a culinary sensation, but it’s fast, simple, and effective. Being strategic about snacks (my go-to is a bag of lupini beans) helps a lot. My fiber goal (hovering around 40-50 grams) is much easier with plant-based diets, and I usually hit it without even making an effort. I take a multi that includes iron, zinc, and of course B12, and also creatine (usually in my morning smoothie). The next step will be to add some probiotics to the mix, as there seems to be research that supports the connection between a healthy gut and increased estrogen production.

The perimenopausal weight gain is not budging, but it’s been rearranging itself differently, and there even seem to be some glimmers of a physique that are really gratifying (the muscular women’s book is a real inspiration!). I’m avidly following marvelous Olympic rugby star Ilona Maher for some liberating inspiration and am enjoying her wisdom very much. My main goal is to get as strong as I can, to increasingly improve my quality of life, and to figure out the next steps in my swimming comeback. Honestly, the fact that the weepiness, constant periods, and nightly sweat lodge seem to be in the rearview mirror is a LOT, and just the fact that I have the energy to do all this makes me very happy.

One factor that seems to be outside my control is the resting scenario. Even with optimal conditions–pitch dark room, reasonable bedtime, ice-cold tart cherry juice before bed–and even with the HRT-induced improvement in my insomnia–it’s still difficult to sleep straight through the night. Grief and fear are very much in the picture, the news intrude into my nightmares, and even though I meditate at night and have a short and beautiful prayer routine upon awakening, there’s only so much I can do with world events and personal trauma against the backdrop of perimenopause. If this is what’s jamming the wheels of my journey, there’s precious little I can do about it that I’m not doing already, and as the Serenity Prayer reminds us, the wisdom to know what we can and cannot control is priceless.

There’s one more thing to add to this snapshot, and that seems to be that my new pastimes seem to be organized around themes of butchy resilience and competence. I started learning to play drums in February, in a really supportive group led by master teacher Brian Gorman, where the hilarious, no-nonsense Gen X energy feeds my soul. I’m in love with this! I’m also in love with my new krav maga class; the new realities of living in this environment have reminded me that knowing how to defend oneself is an important life skill. I don’t need robes, belts, or gurus–I just need to know how to beat the crap out of people if the need arises, and that’s exactly what they teach us at Tactica. It’s terrifying and exhilarating.

All of this reinvention may seem a bit odd, but remember that many life events have hastened it: the death of my beloved father and resulting changes in our family dynamics, the horrors of October 7, the ensuing war, and the resulting devastation of my professional environment, are all part of this. The older I get, the more I feel that what we do–jobs, hobbies, even relationships–is really not who we are. Very little, if anything, of what comprises my daily life is an inalienable part of my identity. The smaller the ego becomes, and the less is wrapped up in it, the better I feel, and these new things that are healthy and life-giving right now are no more a part of me than, say, flute playing or singing or meditation teaching were in the past. It’s just what feels right to do at the moment, and I can revisit as the seasons of my life continue to change.