One of the classic texts that left the most lasting impression on me in grad school was Peter Conrad and Joseph Schneider’s Deviance and Medicalization: From Badness to Sickness. Our marvelous penology professor, the late Leslie Sebba, was deeply interested in the theoretical currents that shape penal ideology, and the shift from moralizing to pathologizing was of great interest to him and, consequently, to us. Conrad and Schneider’s basic argument is that, over time, more and more deviant behaviors that were classified as religious or moral failings, or as evidence of a wicked character, come to be seen in a clinical light. Some examples include a variety of mental illnesses, alcoholism, opiate addiction, homosexuality, delinquency, and child abuse; in a new chapter added long after the original publication date in 1980, they discussed AIDS, domestic violence, co-dependency, hyperactivity in children, and learning disabilities.

The process of medicalizing, or pathologizing, behavior is interesting in itself, as it originates from, and in turn generates, more knowledge, more diagnoses, more professionals, more institutions, and more therapies. But for lawyers, an interesting perspective is how this affects criminal culpability and punishment severity. The law recognizes a narrow subset of cases, in which proven mental illness or defect is so grave that it can be a complete defense (e.g., when the person has no ability to discern what they are doing, or to comprehend the wrongness of their actions, per the M’Naghten Rule.) Some U.S. states and other countries recognize additional paths to a complete acquittal on the basis of mental illness, including irresistible impulses (what happens to a person deemed insane after the acquittal, as Bailey Wendzel explains, is a different story.) But even in cases where mental illness cannot excuse the crime, various clinical conditions can lead to more lenient punishment; lead poisoning, for example, is often brought up as a mitigating factor.

Which is why I was riveted to a recent news item about legal proceedings in the case of Amanda Riley who, as podcast aficionados may know, was convicted in 2021 of fabricating and faking a cancer diagnosis and fleecing supportive friends and fellow churchgoers of more than $105,000. She was sentenced to five years in prison. Riley–referred to in the podcast as Scamanda–went as far as to shave her head and take pictures in actual hospitals, use medical equipment to stage photos that simulated medical treatment, and keep a blog that documented dramatic ups and downs in her treatment journey, including miracle recoveries and last-hope therapies. To get a sense of how profound her deceit was, I highly recommend listening to the podcast, which includes plenty of primary sources and interviews, but obscures some aspects of the case, such as the extent of her husband’s complicity in the ruse (the husband, who did collaborate with her in a vicious custody battle against his ex-wife, was not charged in the case.)

Anyway, Megan Cassidy of the Chronicle reports this morning that Riley’s federal petition for early release was rejected. Here are some of the interesting details:

But Riley’s list of maladies, which were laid out in a recent bid for an early prison release, drew sharp rebuke from prosecutors, who maintain that, yet again, she’s faking it.

“Perhaps not surprisingly … Defendant’s medical records make clear that she does not actually suffer from any acute health problems at all,” U.S. Attorney Michael Pitman said in a reply to Riley’s motion for a sentence reduction this spring.

Citing notes from medical records, Pitman said health care professionals repeatedly witnessed Riley attempting to skew test results: Riley was allegedly seen holding her breath during an oxygen saturation test, manipulating an infusion pump that was administering potassium to her, and “intentionally stress (ing) her body to create tachycardia,” which is a heart rate of more than 100 beats per minute, according to court documents.

Prosecutors said at least four doctors and a nurse wrote in their notes concerns of a possible “factitious disorder,” or listed it as an actual diagnosis. Factitious disorder, also known as Munchausen syndrome, is described by the Mayo Clinic as a “serious mental disorder in which someone deceives others by appearing sick, by purposely getting sick or by self-injury.”

Notably, it was the prosecutors, not the defense, who trotted out the factitious disorder/Munchausen diagnosis. Which, at least to me, exposes a contradiction. The argument against early release is that Riley “does not actually suffer from any acute health problems at all,” but isn’t factitious disorder itself a health problem? One that Riley has, apparently, been diagnosed with by at least one clinician? Not an acute physical malady, but something that undermines some of Riley’s culpability?

If, like me, you’ve watched a bunch of sensational trash TV, you might have encountered Munchausen before and wondered whether it has been exaggerated for dramatic effect. For what it’s worth, factitious disorder is recognized in the DSM-5 and is a legitimate mental health condition. A few factors seem to be important here. First, in terms of differential diagnosis, authors caution that “[i]t is important to distinguish Munchausen from malingering in which an external gain is a primary motivation.” In Riley’s case, I’m unclear on whether it is possible to disaggregate the financial fleecing from the pleasure and attention, which Riley seemed to revel in. She and her family were showered not only with money, but also with affection and adoration. It doesn’t seem to have been merely a cold, calculating scam.

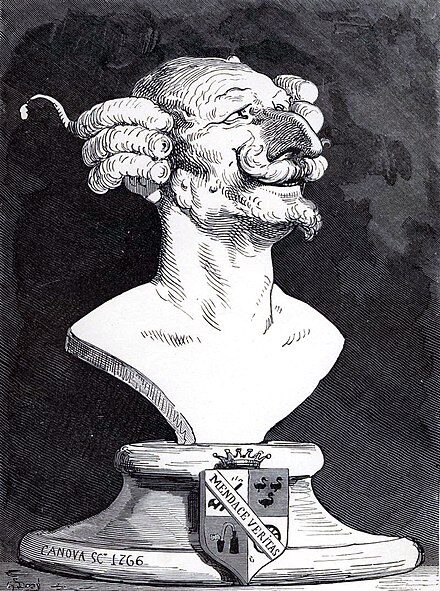

At the same time, the authors remind us that Munchausen patients, as opposed to people suffering from other psychiatric disorders, “have insight into their disorder and are aware that they are fabricating their illness.” This, of course, negates the possibility of wriggling out of criminal culpability, but makes one think back of the eponymous literary character, who was said to believe his own lies.

According to the medical encyclopedia, the standard therapy for factitious disorder patients is psychotherapy, though most patients refuse:

It is not necessary for the patient to admit to their factitious disorder and, in fact, most patients rarely do.

In certain cases, it may be helpful to target cognitive-behavioral therapy toward childhood trauma that could be the instigator for the disorder. It has also been concluded that various medical interventions such as anti-depressants and/or anti-psychotics showed no benefit in the disorder.

This raises a thorny question from a criminal law standpoint. Someone who seems to be resistant to treatment might embark on a similar course of action when they get out. But if they do, isn’t that proof that there’s something about them that is pathological and resistant to treatment, and therefore their misdeeds are, perhaps, less culpable than those of a healthy, calculating malingerer?

I also worry about the extent to which social media, Tik Tok in particular, encourages people, especially teens, to self-diagnose as suffering from a variety of ailments and parade the symptoms online. As sympathies pour in the form of likes and reposts, folks who already have a tendency for seeking attention through malingering will have more incentive to engage in this behavior, further blurring the line between pathology and grift.

The podcast portrays Riley in a decidedly unsympathetic manner, which is understandable given that the interviewees are, for the most part, people caught in her web of lies. I think there are both retributivist and utilitarian reasons why a five-year sentence is adequate here. The extent of the deceit, the exploitation of good people, the devastation of extended family, the way incidents like this make it harder for people whose medical problems are genuine to be trusted and receive help (“boy who cried wolf”, the detrimental effect that Doron Dorfman investigates in Fear of the Disability Con), and the risk she’ll do it again, are all fair reasons for it. But I, for one, would be interested in further elaborating the path we take when pathology enters the conversation.

No comment yet, add your voice below!