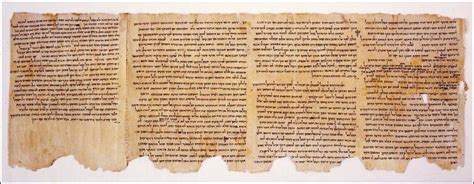

This fall I have the great joy of auditing James Nati‘s excellent course on the Dead Sea Scrolls, which were discovered in Qumran in the late 1940s and led to a huge quest to procure the corpus, which dispersed into a variety of hands in the following decades. One of the most successful quests to obtain the archaeological artifacts and bring them back, the scrolls have now been digitized, and we read the primary text and some commentary on it in class. To challenge myself, I try to read it out of the original papyrus, imagining myself touching and smelling the manuscripts.

It’s been particularly intriguing to read this stuff as someone who knows next to nothing about the cults at the time, but knows quite a bit about movements, sects, etc., in the 1960s and 1970s. When I studied Israelite/Jewish history in middle and high school, it was common to lump the Dead Sea folks together and refer to them as the Essenes (a term that comes from Josephus and Philo) and assume that they were a bunch of hippies in white robes who liked to bathe a lot. I’m finding out that newer historians and theologians now believe that the scrolls are not necessarily the work of one isolated sect, but rather of people who might have had considerable ties to the outside; the Community Rule includes some references to behavioral norms when outside of the compound. Also, the Yahad people, to whom the Community Rule refers, and the composers of the Damascus Document might have been two different groups.

Stuff like this makes me wish I could time-travel and see how that scene differed from what I saw when I looked at the cults and new movements of the 1960s with all their eccentricities and splintering. The idea that these folks would have to at least trade with the outside world makes a lot of sense to me, because they lived in the desert and would have had to procure food somehow, at the very least. Also, the idea that their splintering might be about personal ego clashes as much as about theological differences resonates with what I know about the 1960s. The eschatological stuff reminds me a lot of the narratives of various cultish sects even today, who assume that at some point all the wrongdoers will perish while the righteous folks will remain or be taken to the heavens. Do we have, as a species, some sort of cult blueprint that repeats itself in various groups?

A couple of decades ago I came across Isaac Bonewits’ tool for evaluating cults. I wish we had a good enough picture of the Yahad people and/or the Damascus Document people to apply the tool and figure out what was really happening there. The eschatological stuff reminds me a lot of the narratives of various cultish sects even today, who assume that at some point all the wrongdoers will perish while the righteous folks will remain or be taken to the heavens. Moreover, it certainly seems that a big part of the righteousness is about strict norms and regulations (e.g., what to do on the Sabbath, ritual and meal planning, hierarchy, personal and spiritual cleanliness) that far exceed those that presumably were practiced in mainstream society. One has to wonder: do we have, as a species, some sort of cult blueprint that repeats itself in various groups? Is there anything new under the sun?

No comment yet, add your voice below!