(published: The Green Bag 27(3), Spring 2024)

INTRODUCTION

J.R.R. Tolkien’s immortal Lord of the Rings tells of the crossing of the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, during which members of the Fellowship of the Ring inadvertently awaken the Balrog. A monstrous holdover from ancient times, the Balrog attacks the Fellowship. Gandalf, the wizard leader of the Fellowship, successfully fights the monster, but at the very last moment, as the Balrog plunges to its death, it swings its whip one last time, capturing Gandalf and dragging him along into the abyss under the Bridge of Khazad-dûm.

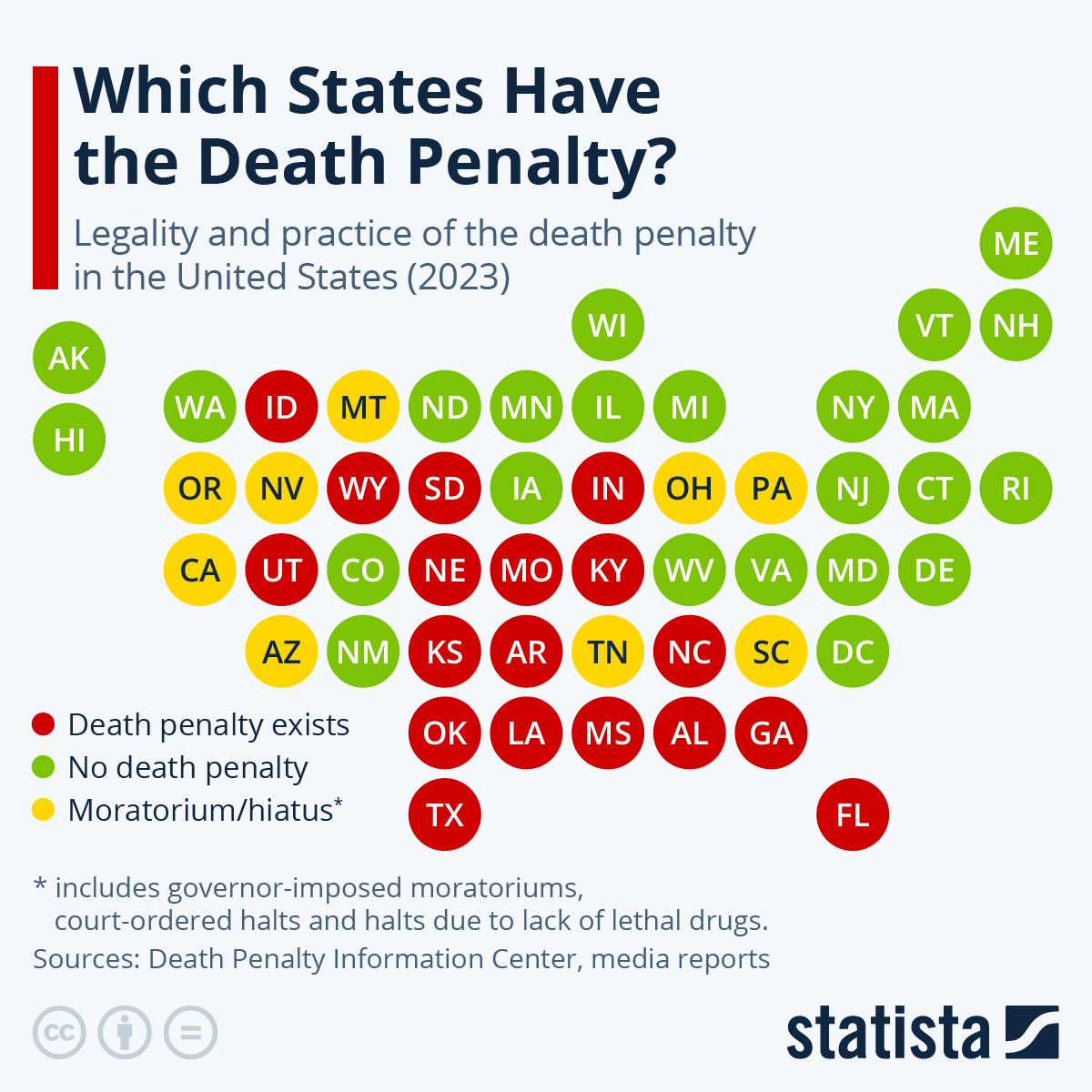

The U.S. death penalty in the 21st century is like the Balrog – arcane, decrepit, still grasping and lashing its whip even as it approaches its demise. The score, state-by-state, is practically against capital punishment: 23 states have abolished it, and out of the 27 states that retain it, six (plus the federal government under President Joe Biden) have instated moratoria upon its use.

Even in retentionist states, the rate of executions has slowed almost to a grinding halt, and initiatives to abolish the death penalty frequently appear on the ballot. Even as Americans hang on to their support of the death penalty by a thread,3 and these ballot initiatives continue to be defeated,4 the death penalty continues to lose practical ground.5 Much like people on death row, most of whom die natural deaths after decades of incarceration and litigation,6 the death penalty itself is dying a slow, natural death.

As Ryan Newby and I explained more than a decade ago, the slow decline of the death penalty has been caused by a confluence of several factors.7 The first is the advent of cheap-on-crime politics in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008, which drew attention to the immense, disproportionate expenditure on capital punishment. 8 The second is the rising prominence of the innocence movement, which has shone a light on the widespread problem of wrongful convictions, supported in recent years by

the popular reach of true-crime podcasts highlighting miscarriages of justice.9 The third is the growing attention to racial disparities in criminal justice which, while a tough argument to bring up in litigation,10 has impacted the national policy field through Obama-era reforms.11

The expense, discrimination, and potential for harrowing mistakes are all aspects of the chronic disease afflicting the death penalty. But like many natural deaths from chronic disease, the end is prolonged, undignified, and sometimes bitingly cruel. Anyone who has cared for a loved one through the end of life can probably recall the chaotic, arbitrary, sometimes contradictory indignities that every day of decline brings in its wings. And so, in this paper, I offer you a safari tour of horrors, injustices, absurdities, and embarrassments that have characterized the death penalty through its prolonged chronic demise.

TRUMP’S LAST KILLING SPREE: RELUCTANT VICTIMS, ALZHEIMER’S, AND JURISDICTIONAL DISPARITIES

Tolkien is a master storyteller, and he sets up the moment when the Balrog’s whip ensnares Gandalf as poignantly tragic – a sudden, unnecessary reminder that, even at its demise, the ancient monster can still unleash vicious harm. The last few days of the Trump administration offered ample proof of this, through the Supreme Court’s decision in Barr v. Lee.12

Like much of latter-day death penalty litigation, Lee focused on chemicals used in federal executions – to wit, a single shot of pentobarbital, a mainstay of state executions as European countries no longer export lethal drugs to the U.S.13 As Ryan Newby and I explained in 2013, this sort of litigation is a classic example of what Justice Harry Blackmun referred to in the early 1990s as “tinkering with the machinery of death.” Blackmun could afford a direct, stop-beating-around-the-bush approach to the tiresome and technical minutiae of postconviction litigation, but capital defense lawyers cannot; arguments about human rights and racial disparities have long been futile, for various procedural reasons, and the limits of the sayable on appeal and on habeas revolve around chemicals and number of injections. Barr v. Lee, decided 5-4, was no exception: the plaintiffs, whose cases were final and cleared for executions, provided expert declarations correlating pentobarital use to flash pulmonary edema, a form of respiratory distress that temporarily produces the sensation of drowning or asphyxiation. The federal government provided contrary expert testimony, according to which pulmonary edema occurs only after the prisoner has died or been rendered

fully insensate. The Supreme Court found, per curiam, that the plaintiffs had not carried the burden of proof and cleared the way for the executions. Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent echoed Blackmun’s distaste for what death penalty litigation has become, remarking, “[t]his case illustrates at least some of the problems the death penalty raises in light of the Constitution’s prohibition against ‘cruel and unusual punishmen[t].’” Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in turn, remarked on the absurdity of doing justice to fundamental questions via “accelerated decisionmaking.”

Then came three troubling executions. Daniel Lewis Lee was put to death against the express, vocal, and repeated wishes of his victims’ families to spare him.14 The judicial and executive branches’ trampling of those requests followed the usual capital punishment theater in which, as Sarah Beth Kaufman explains in American Roulette, prosecutors, governors, and death penalty advocates use victims as props, assuming that punitiveness is faithful to their wishes – a position that does not faithfully represent the diverse views among victims of violent crime.15 According to the first-ever national survey of crime, twice as many victims prefer that the criminal justice system focus more on rehabilitation than on punishment; victims overwhelmingly prefer investments in education and in job creation to investments in prisons and jails, by margins of 15-to-1 and 10-to-1 respectively; by a margin of 7-to-1, victims prefer increased investments in crime prevention and programs for at-risk youth over more investment in prisons and jails; and 6 in 10 victims prefer shorter prison sentences and more spending on prevention and rehabilitation than on lengthy prison sentences.

Then, the federal government executed 68-year-old Wesley Purkey, who was described by his lawyer, Rebecca Woodman, as a “severely braindamaged and mentally ill man who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease” and does not understand “why the government plans to execute him.”16 The debate over Purkey’s mental illness was emblematic of the decades and billions of dollars spent poring over the fitness for execution of elderly, decadeslong death row residents. It also made a mockery of Atkins v. Virginia,

17 which forbade the execution of mentally challenged people but left it up to individual jurisdictions to duke out the details of who, precisely, they deem smart or sane enough to be injected with pentobarbital.

Finally came Dustin Honken’s execution, which offered a grim reminder of the gap between the inexplicable federal enthusiasm for executions and the waning interest of states in the penalty. Honken was the first person from Iowa to be executed since 1963; Iowa abolished the death penalty in 1965. Honken’s lawyer, Shawn Nolan, said, “There was no reason for the government to kill him, in haste or at all. In any case, they failed. The Dustin Honken they wanted to kill is long gone. The man they killed today was a human being, who could have spent the rest of his days helping others and further redeeming himself.”18

Another development was the reintroduction of electrocutions and firing squads as permissible execution methods by the administration of President Donald Trump in late November 2020 – after Biden had defeated Trump in the presidential election. The change was intended to offer federal prosecutors a wider variety of options for execution in order to avoid delays if the state in which the inmate was sentenced did not provide other alternatives. At the same time, the Department of Justice said it would keep federal executions in line with state law: “the federal government will never execute an inmate by firing squad or electrocution unless the relevant state has itself authorized that method of execution.”19

Trump’s appetite for executions was, at least, consistent with his positions on capital punishment since the 1980s, when he regularly purchased large ads and gave interviews advocating for the death penalty for the Central Park Five20 (who have since been exonerated, as is well known). In the early days of his presidency, he chased headlines expressing support for capital punishment for drug dealers.21 While consistent with Trump’s presidential positions, the viciousness of his last-minute addition of federal electrocutions and firing squads seemed pointless, since Biden was known to oppose the death penalty and had made campaign promises to work toward federal abolition.22 Moreover, any effort to electrocute or shoot death row convicts would embroil the federal government in interminable Eighth Amendment litigation, given the always-present risk of botched executions.

The last slew of planned Trump executions included more cases that provoked moral anguish. For example, the execution of Lisa Montgomery, the only woman on federal death row.23 Montgomery’s crime was shockingly brutal. She strangled a pregnant woman before cutting her stomach open and kidnapping her baby. Her own experiences of victimization were torturous and harrowing. She was sexually assaulted by her father starting at 11 years old, trafficked by her mother, and horrifically abused by her stepbrother, who became her husband. She was involuntarily sterilized, deteriorated into severe mental illness, and lived in abject poverty at the time the crime was committed. The uproar about the sentence provoked heated debates about the Trump administration’s appetite for creating controversies that the Biden administration would then have to undo. What is the point, one might ask, of all this cruelty? And the answer, as Adam Serwer wrote in a different context, might be: the cruelty is the point.24

OKLAHOMA: CHEMICALS AND INNOCENCE

A tragic Talmudic story tells how Yehuda ben Tabbai, President of the Sanhedrin, once wrongly convicted a man of perjury. By the time ben Tabbai realized his mistake, it was too late; the man had already been put to death. Shocked by his complicity in injustice, ben Tabbai would never again rule singlehandedly on a legal point, and every day of his life he would prostrate himself on the grave of the wrongly executed man, begging forgiveness and weeping.25

One wishes that more judicial and executive officials would take a page from ben Tabbai’s book. Instead, a sense of confusion, lack of commitment, and being in perpetual limbo has characterized capital punishment for the last decade. The story of Richard Glossip, the lead petitioner in Glossip v. Gross, is a case in point. In 2015, the Supreme Court rejected Glossip’s petition against the use of midazolam in his execution, just a brief time after the same drug played a horrendous part in the botched execution of Clayton Lockett. In line with the aforementioned trend of technical litigation, the decision revolved around whether Glossip had shown that Oklahoma had better execution methods than midazolam.26

Anyone reading the decision could be forgiven for having no idea that Glossip is widely believed to be innocent, and that Oklahoma’s Attorney General, who reviewed his case, does not stand behind the conviction. Nevertheless, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals would not halt Glossip’s execution. Judge David Lewis wrote that the case “has been thoroughly investigated and reviewed,” with Glossip given “unprecedented access” to prosecutors’ files, “[y]et he has not provided this court with sufficient information that would convince this court to overturn the jury’s determination that he is guilty of first-degree murder and should be sentenced to death.” It took yet another petition to the U.S. Supreme Court to halt the execution.27

CALIFORNIA: DEATH BY MORATORIUM

For more ambiguity and discombobulation on the death penalty in the 21st century, consider California, where several rounds of abolitionist voter initiatives failed in the last decade.28 I want to spend more time discussing California, not only because I am intimately familiar with capital punishment law where I live and work, but also because I think the last decade in the Golden State perfectly encapsulates what a chronic, slow death for capital punishment looks like. In 2016, while narrowly defeating the abolitionist Prop 62, California voters narrowly approved Prop 66, which was supposed to speed up executions, as well as allow death row residents to be relocated to other prisons where they could pay restitution to their victims. Some aspects of Prop 66 – specifically, those which remove safeguards against wrongful executions – have been found unconstitutional, but most of it has survived constitutional review.29

When explaining what the death penalty in California was like in the late 2010s, I sometimes borrow a framework from the construction world. When planning a project, general contractors might draw a triangle, writing in each corner one word – respectively, “good,” “fast,” and “cheap.” They then say to the client, “you can’t have all three; pick two.” This is an apt description of why death penalty opponents often refer to California’s capital punishment as “broken beyond repair.” A “good” and “cheap” death penalty would require finding some way to seriously litigate postconviction motions on a lengthy timeline and on a shoestring, relying mostly on California’s minuscule existing cadre of capital habeas litigators. Cases would drag on and on, as they do now, until people received representation, a situation that at least one federal judge found to violate the Eighth Amendment.30 A “good” and “fast” death penalty, which is what some supporters of Prop 66 perhaps wanted, would require massive expenditures so that proper, high-quality representation could be found and habeas writs could efficiently work their way through the courts. A “fast” and “cheap” death penalty, which is what Prop 66 might have produced had all its aspects been found constitutional, would do away with many safeguards against wrongful executions and result in more deadly mistakes. Even if

one approves of capital punishment in theory, as many California voters do (for example, through a retributive framework), it is therefore hard to compare its abstract form to the way it is administered in practice: There is no way of fashioning capital punishment in California in a way that guarantees it to be “good,” “fast,” and “cheap.”

These concerns, and many others, led California Governor Gavin Newsom to take a step that his abolitionist predecessors had shied away from: placing a moratorium on the death penalty in California and ordering the

death chamber dismantled.31 Newsom is also turning San Quentin prison, home to the country’s largest death row, into a Scandinavian-style “center for innovation focused on education, rehabilitation and breaking cycles of crime.” For the first time in decades, residents of death row are able to move freely within the facility, and many of them will be transferred to other facilities, a monumental change in their life circumstances that some death row residents, acclimated to their peculiar, restrictive lives, view with apprehension.32 But these are executive, not legislative acts. Because the death penalty still has a legal, if not ontological, existence, people whose lives were saved by the moratorium are still, legally, capital convicts, and costly postconviction litigation on their cases continues, to the tune of $150 million per annum.33

To cynical commenters, who might observe that this new incarnation is not “good,” “fast,” or “cheap,” one might respond, “at least we’re not executing people.” But saying, “no one is being executed on death row” is

far from saying, “no one dies on death row.” In late May 2020, as a San Francisco Chronical exposé revealed – and as a subsequent investigation by the California Inspector General’s office and litigation in state courts confirmed – San Quentin, still home to the country’s largest death row, was overcrowded to 113% of design capacity.34 Alarmed by a horrific COVID19 outbreak at the California Institute of Men in Chino, custodial and

medical officials there sought to mitigate the spread by transferring 200 men out of the facility, 122 of them to San Quentin. The men were not tested for COVID-19 for weeks prior to their transfer. On the morning of

the transfer, several transferees told nurses that they were experiencing COVID-19 symptoms (fever and coughing). According to email correspondence between health officials, these men were treated as malingerers and the transfer proceeded as planned. No effort was made to facilitate social distancing within the buses; the transferees heard and felt their neighbors cough throughout the lengthy journey to the destination facilities.35

The virus spread quickly throughout San Quentin. By the end of June, more than three quarters of the prison population had been infected and 29 had died – 28 prisoners and one worker.36 San Quentin’s death row was especially vulnerable to COVID-19, both because of the low quality of the physical plant – a dilapidated, poorly constructed, and thinly staffed long-term home to approximately 750 men (now many fewer) – and because the death row population tends to be older and sicker than the general prison population. The virus tore quickly through death row, and while prison authorities did what they could to obscure the calamities, San Francisco Chronicle journalists broke the story:

A coronavirus outbreak exploding through San Quentin State Prison has reached Death Row, where more than 160 condemned prisoners are infected, sources told The Chronicle on Thursday. One condemned inmate, 71-year-old Richard Eugene Stitely, was found dead Wednesday night. Officials are determining the cause of death and checking to see whether he was infected.

State prison officials declined to confirm that the virus has spread to Death Row, but three sources familiar with the details of the outbreak there provided The Chronicle with information on the condition they not be named, and in accordance with the paper’s anonymous source policy. Two of the sources are San Quentin employees who are not authorized to speak publicly and feared losing their jobs.

There are 725 condemned inmates at San Quentin, and of those

who agreed to be tested for the coronavirus, 166 tested positive, the

sources said. . . .

It is unclear whether Stitely was infected with the coronavirus. He refused to be tested, according to the three sources with knowledge of the situation.37

By contrast to general population residents, whose identities were hidden from the public for medical privacy reasons, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation sent emails to interested parties about

deaths of people on death row, listing their names and full details. Through subtracting the named casualties from the total death toll, a horrifying truth emerged: More people died on death row from COVID-19 under Newsom’s moratorium than California had executed since the reestablishment of the death penalty in 1978.38

This outcome was deeply ironic, because even after the moratorium, with no death chamber and bereft of lethal chemicals, California courts continued to be clogged with death penalty litigation concerning details

revolving around whether various modes and aspects of the execution process are “cruel and unusual” even as the death penalty itself was still deemed “kind and usual.”39 Flying in the face of this precious and expensive effort to sever the death penalty from any of its potentially cruel and unusual implications were executions clearly not prescribed by the California Penal Code: deaths from a contagious pandemic, compounded by incompetence and neglect.

At the same time, even stalwart supporters of the death penalty realized that capital verdicts that will never be carried out make no sense, logically or practically. In summer 2020, Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, by no means a capital-punishment-shy public prosecutor, announced that his office would no longer seek the death penalty. Rosen claimed that his visit to the Civil Rights Museum in Alabama inspired him to see the death penalty not only “through eyes of the victims and families of those whose lives were taken,” but also “through the lens of race and inequity.” The rationales he offered for the policy change were in line with those behind the penalty’s decline in popularity more generally: “These cases use up massive public resources and cruelly drag on for years with endless appeals that give no finality to the victims’ families,” he said. “There’s the tragic but real risk of wrongful conviction. And, shamefully, our society’s most drastic and devastating law enforcement punishment has been used disproportionately against defendants of color.”40 Rosen was facing an election challenge from a more progressive candidate, which could partly explain his change in position. Nevertheless, his reliance on the more general arguments means that the gubernatorial changes at San Quentin did resonate.

Perhaps even more important was the announcement by George Gascón, upon his election as Los Angeles District Attorney in fall 2020, that the county would no longer seek the death penalty41 – an inflection point for one of California’s four “killer counties” and one of the entire country’s three highest sources of capital sentences. 42 Even more striking is a remarkable data point from Sacramento: Joseph DiAngelo, otherwise known as the Golden State Killer, was finally caught and convicted using innovative forensic investigative tools.43 The Sacramento County prosecutor did not even ask for the death penalty, and rightly so, as it would have allowed DiAngelo to continue litigating at the state’s expense only to die a natural death, like everyone else on death row. Which raises a fair question: If not the most notorious and heinous criminal in the history of California, then who?

WHAT DEATH PENALTY EUTHANASIA MIGHT LOOK LIKE

Capital punishment’s last gasps are, as these examples show, rife with inconsistencies, ironies, and changes of direction, which raise the question when, and how, the end will come. As public opinion and results at the ballot box show, the death penalty retains a symbolic hold over the American imagination. But judges and politicians are exposed to its unsavory sides.

It is hard to provide facile explanations for the different modes of the capital penalty’s demise in recently abolitionist states. In Washington, abolition arrived through a judicial decision about racial disparities in the penalty’s application;44 in Delaware, through a case involving arbitrary jury decisions in capital cases, which was later extended to the remaining cases on death row;45 in New Hampshire, through a non-retroactive statute; 46 in Colorado, through a combination of a statute and gubernatorial commutations;47 in Virginia, the first Southern state to abolish the death penalty, through a bipartisan legislative vote.48

One is left wondering whether it is easier to get rid of the death penalty in retentionist states – such as in Illinois, where abolition followed Governor George Ryan’s mass commutations, largely due to his concerns about innocence and wrongful executions49 – or in states with moratoria – such as California, where one wonders whether the dismantlement of the death chamber and the disbanding of death row, along with the vanishing prospect of an execution as a lightning rod, might be slowing down the dismantling of the death penalty itself. Without the physical reminder of the remnants of this archaic punishment, and with the growing resemblance of the death penalty to the two other members of the “extreme punishment trifecta” (life with and without parole),50 does the effort to abolish a thoroughly defanged (but still expensive) death penalty lose its steam?

What signals a new phase in the death penalty’s terminal illness is a combination of factors: a critical mass of abolitionist states; backlash caused by the Trump administration’s execution spree; the absence of capital sentencing nationwide and, especially, in high-profile cases; abolitionist thinking and decisionmaking at the county prosecution level; the specter of COVID-19 deaths; and, of course, the ever-rising costs. We are unlikely to see a definitive kiss of death. Instead, many local developments may eventually mean – perhaps, to our surprise – that, like so many people on death row itself, capital punishment has died a quiet, natural death.

NOTES

1 J.R.R. TOLKIEN, THE LORD OF THE RINGS: THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING bk. II, ch. 5

(2012 [1954]).

2 Abolitionist states with date of abolition: Alaska (1957), Colorado (2020), Connecticut (2012), Delaware (2016), Hawaii (1957), Illinois (2011), Iowa (1965), Maine (1887), Maryland

(2013), Massachusetts (1984), Michigan (1847), Minnesota (1911), New Hampshire (2019),

New Jersey (2007), New Mexico (2009), New York (2007), North Dakota (1973), Rhode

Island (1984), Vermont (1972), Virginia (2021), Washington (2023), West Virginia (1965),

Wisconsin (1853). Retentionist states (including states with moratoria): Alabama, Arizona,

Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana,

Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma,

Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Wyoming.

States with moratoria, along with moratorium date: California (2019), Pennsylvania (2023),

Oregon (2022), Arizona (2023), Ohio (2020), Tennessee (2022). The federal moratorium

was put in place by the Biden administration in 2021. Source: Death Penalty Information

Center (“Death Penalty Info”) website, deathpenaltyinfo.org/states-landing. 3 Megan Brenan, “Steady 55% of Americans Support Death Penalty for Murderers,” Gallup, Nov. 14, 2022.

4 AUSTIN SARAT, JOHN MALAGUE, AND SARAH WISHLOFF, THE DEATH PENALTY ON THE

BALLOT: AMERICAN DEMOCRACY AND THE FATE OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT (2019).

5 DANIEL LACHANCE, EXECUTING FREEDOM: THE CULTURAL LIFE OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

IN THE UNITED STATES (2016).

6 166 non-execution deaths, as of 2024: Death Penalty Focus, deathpenalty.org/facts/.

7 Hadar Aviram and Ryan Newby, “Death Row Economics: The Rise of Fiscally Prudent

Anti-Death Penalty Activism,” 28 CRIM. JUST. 33 (2013).

8 HADAR AVIRAM, CHEAP ON CRIME: RECESSION-ERA POLITICS AND THE TRANSFORMATION

OF AMERICAN PUNISHMENT (2015).

9 Keith A. Findley, “Innocence Found: The New Revolution in American Criminal Justice,”

in CONTROVERSIES IN INNOCENCE CASES IN AMERICA 3-20 (2016); Lindsey A. Sherrill,

“Beyond Entertainment: Podcasting and the Criminal Justice Reform ‘Niche,’” and Robin

Blom, Gabriel B. Tait, Gwyn Hultquist, Ida S. Cage, and Melodie K. Griffin, “True

Crime, True Representation? Race and Injustice Narratives in Wrongful Conviction Podcasts,” in TRUE CRIME IN AMERICAN MEDIA 67-82 (2023).

10 McClesky v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987).

11 Barack Obama, “The President’s Role in Advancing Criminal Justice Reform,” 130 HARV.

L. REV. 811 (2017).

12 Barr v. Lee, 591 U.S. 979 (2020).

13 “Europe’s moral stand has U.S. states running out of execution drugs, complicating capital

punishment,” CBS NEWS, Feb. 18, 2014.

14 Hailey Fuchs, “Government Carries Out First Federal Execution in 17 Years,” NEW YORK

TIMES, July 14, 2020.

15 SARAH BETH KAUFMANN, AMERICAN ROULETTE: THE SOCIAL LOGIC OF DEATH PENALTY

SENTENCING TRIALS (2020).

16 Khaleda Rahman, “U.S. Executes Wesley Purkey, Who Calls It a ‘Sanitized Murder’ In

Last Words,” NEWSWEEK, July 16, 2020.

17 Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

18 Shawn Nolan, “Statement From Shawn Nolan, Attorney For Dustin Honken,” FEDERAL

DEFENDER, July 17, 2020.

19 Matt Zapotosky and Mark Berman, “Justice Dept. rule change could allow federal executions by electrocution or firing squad,” WASHINGTON POST, Nov. 27, 2020.

20 Colby Itkowitz and Michael Brice-Saddler, “Trump still won’t apologize to the Central

Park Five. Here’s what he said at the time.” WASHINGTON POST, June 18, 2019.

21 Michael Krasny, “President Trump Announces Plan to Fight Opioid Abuse, Including

Death Penalty,” KQED FORUM, Mar. 20, 2018.

22 Dakin Andone, “Biden Campaigned on Abolishing the Federal Death Penalty. But 2 Years

In, Advocates See an ‘Inconsistent’ Message,” CNN, Jan. 22, 2023.

23 Reuters, “Lisa Montgomery: US Executes Only Woman on Federal Death Row,” BBC

WORLD, Jan. 13, 2021.

24 Adam Serwer, “The Cruelty Is the Point,” THE ATLANTIC, Oct. 3, 2018.

25 Bavli Hagiga 16:2.

26 Glossip v. Gross, 576 U.S. 863 (2015); Jeffrey E. Stern, “The Cruel and Unusual Execution

of Clayton Lockett,” THE ATLANTIC, June 15, 2015.

27 Glossip v. State, www.okcca.net/cases/2023/OK-CR-5/ (2023); Glossip v. Oklahoma, 143.Ct. 2453 (2023).

28 Prop 34 failed in 2012: David A. Love, “Prop 34 Fails But Signals the Imminent Demise

of California’s Death Penalty,” THE GUARDIAN, Nov. 9, 2012. Prop 66 failed in 2016:

Sarah Heise, “Death Penalty Supporters Claim Victory with Failure of Prop 62,” KCRA3, Nov. 9, 2016.

29 Bob Egelko, “California Supreme Court Upholds Most Of Expedited Death Penalty

Initiative,” SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE, Aug. 24, 2017.

30 Jones v. Chappell, 31 F. Supp. 3d 1050 (C.D. Cal. 2014).

31 Kyung Lah, “How Kamala Harris’ Death Penalty Decisions Broke Hearts on Both Sides,”

CNN, Apr. 8, 2019; Eric Westervelt, “California Says It Will Dismantle Death Row.

The Move Brings Cheers and Anger,” NPR, Jan. 13, 2023.

32 Nigel Duara, “Gavin Newsom Moves to ‘Transform’ San Quentin as California Prison

Population Shrinks,” CALMATTERS, Mar. 21, 2023; Sam Levin, “The Last Days of Death

Row in California: ‘Your Soul is Tested Here’,” THE GUARDIAN, May 1, 2023.

33 Arthur Rizer and Marc Hyden, “Why Conservatives Should Oppose the Death Penalty,”

THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE, Jan. 10, 2019.

34 Mary Harris, “California’s Carelessness Spurred a New COVID Outbreak,” SLATE, July 7,2020; Roy W. Wesley and Bryan B. Beyer, “COVID-19 Review Series, Part Three,” OFFICEOF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL STATE OF CALIFORNIA, Feb. 1, 2021, 1-2, www.oig.ca.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2021/02/OIG-COVID-19-Review-Series-Part-3-%E2%80%93-Transferof-Patients-from-CIM.pdf; “Monthly Report of Population As of Midnight June 30, 2020,”CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION, July 1, 2020, 2, www.cdcr.ca.gov/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/174/2020/07/Tpop1d2006.pdf.

35 For a thorough examination of COVID-19 and California’s death row, see HADAR AVIRAM AND CHAD GOERZEN, FESTER: CARCERAL PERMEABILITY AND CALIFORNIA’S COVID19 CORRECTIONAL DISASTER (2024).

36 Daniel Montes, “Trial Over COVID-19 Outbreak at San Quentin State Prison That Left29 Dead to Begin Thursday,” BAY CITY NEWS, May 20, 2021.Euthanize the Death Penalty AlreadySPRING 2024 193

37 Megan Cassidy and Jason Fagone, “Coronavirus Tears through San Quentin’s Death Row;

Condemned Inmate Dead of Unknown Cause,” SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE, June 25, 2020,

www.sfchronicle.com/crime/article/Coronavirus-tears-through-San-Quentin-s-Death15367782.php.

38 Patt Morrison, “California Is Closing San Quentin’s Death Row. This Is Its Gruesome

History,” LOS ANGELES TIMES, Feb. 8, 2022.

39 Aviram & Newby, supra note 7; George Skelton, “In California, the Death Penalty is Allbut Meaningless. A Life Sentence for the Golden State Killer Was the Right Move,” LOSANGELES TIMES, July 2, 2020.

40 Quoted in Michael Cabanatuan, “Santa Clara County DA Jeff Rosen No Longer to SeekDeath Penalty,” SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE, July 22, 2020.

41 Alexandra Meeks and Madeline Holcombe, “New Los Angeles DA Announces End to

Cash Bail, the Death Penalty and Trying Children as Adults,” CNN, Dec. 8, 2020.

42 “Death Penalty Info: ACLU Study: Los Angeles Death Penalty Discriminates Against

Defendants of Color and the Poor,” deathpenaltyinfo.org/news/aclu-study-los-angelesdeath-penalty-discriminates-against-defendants-of-color-and-the-poor.

43 Paige St. John, “The Untold Story of How the Golden State Killer Was Found: A Covert

Operation and Private DNA,” LOS ANGELES TIMES, Dec. 8, 2020.

44 State v. Gregory, 427 P.2d 621 (Wash. 2018).

45 “Death Penalty Info: Delaware,” deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state/

delaware.

46 “Death Penalty Info: New Hampshire,” deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/stateby-state/new-hampshire.

47 “Death Penalty Info: Colorado,” deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state/

colorado.

48 “Death Penalty Info: Virginia,” deathpenaltyinfo.org/news/virginia-legislature-votes-toabolish-the-death-penalty.

49 Sarah Schulte, “20 Years After Commuting 167 Illinois Death Sentences, Ex-Gov.

George Ryan Has No Regrets,” ABC7 CHICAGO, Jan. 10, 2023.

50 HADAR AVIRAM, YESTERDAY’S MONSTERS: THE MANSON FAMILY CASES AND THE ILLUSION

OF PAROLE (2020).