On the heels of finishing the manuscript for my next book, Behind Ancient Bars, we’re taking a much-needed Thanksgiving break in Mendocino. The breathtaking vistas and calm atmosphere are an opportunity to rest, lift, swim, play, and read at a different pace, one I have missed lately while working and studying full time.

One thing I’m doing on this break, whenever some downtime is available, is reading. From an actual book, not from a screen. It is a sensation I have missed and longed for, and yet it feels unfamiliar and not as easy as it was in my childhood. A few times during my GTU journey we were encouraged by our professors–and rightly so–to print out the materials and read them on paper or to purchase the books in hardback or paperback. I’m sorry to say I didn’t always take them up on their invitation to engage with the text in a more tactile way, for a simple reason: I commute by bicycle and train and carrying a lot of books or printed paper with me is much more of a chore than carrying a MacBook Air. It’s true that reading from a screen opens the door to online distractions, and even though I use software that locks down the worst offenders, the temptation nags at me. Believe me, the irony of typing about this onscreen for people to read onscreen, and also the irony of teaching using an electronic casebook, have not escaped me, but the convenience can’t be beat–nor can the price, in the case of multiple hefty textbooks.

While here, though, I’ve started to read Maryanne Wolf’s Reader, Come Home, about the impact that digital reading and engagement has on our cognitive process. She focuses mostly on children, because they don’t have the analog background that us “olds” do, but honestly, after decades of working on a screen, I know exactly what she’s talking about. It feels like the synapses in my brain have changed to accommodate a completely new way of thinking, and I miss some aspects of my old cognitive ways. I’m finding the printed page challenging to engage with. My mental acuity, focus, and concentration are not what they were, and it’s probably not just aging–it’s aging while living digitally.

There are a bunch of things that remind me that I’m aging. Layers of superfluous stuff are being shed. Comfort in my own skin takes precedence. My faith in knowing The Truth (or that it can even be known, or held exclusively by one group or one side) has eroded, and I’m more comfortable asking questions and listening. Chronic conditions and issues start amassing, things that need attention. More and more precious people are gone, more lights are dimmed, and a lot of new stuff fades into irrelevance. Alongside these things comes an urgency to preserve and improve my mental acuity, and a big part of that is to learn to read again off a printed page, redevelop long-term concentration, and choose what and how I read intentionally and with care.

I’m especially enjoying reading new takes and angles on classic works that have accompanied my life. Being a big lover of Jane Austen, I Appreciated Ruth Wilson’s The Austen Remedy, and I now enjoy engaging with works that expand and challenge my view of the classics: Jo Baker’s Longbourn, which tells the Pride and Prejudice story from the perspective of the servants, and Claudia Gray’s mystery series featuring the second generation of some Austen characters. Along the same lines, I’m enjoying Percival Everett’s James, which retells the Huckleberry Finn story from the wry, witty, and compassionate perspective of Jim, the enslaved man who is so infantilized and ridiculed in the original. Same deal with Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, which sheds a Dickensian light on some of the poor of this land (my new book engages with Bleak House and with Oliver Twist, so I have a new fondness for seeing how these perennial stories play out in different times and places). Charles Finch’s mystery novels are a delight to revisit. And I’m enjoying revisiting the flawed and complex heroes at the heart of Ann Cleves’ mystery novels: the Matthew Venn and Vera Stanhope series. I’m also enjoying reading about natural history–especially about trees and mushrooms–and about the impact of music, exercise, art, the outdoors, etc., on the human mind and body.

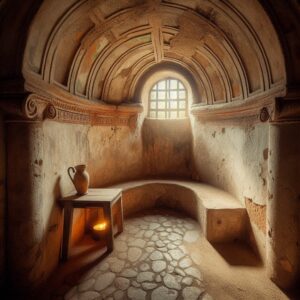

It was interesting to think about reading on page and off page when taking the Dead Sea Scrolls class. Most of my classmates, who are not native Hebrew speakers, challenged themselves–and did admirably–with the Hebrew text (with no nikud). To take on an equivalent challenge, I tried to read each scroll in the original, which is to say, from a digital imaging of the original papyrus. It’s still a screen, of course, but it made some of the experience palpable in the sense that it provoked the excitement of looking at words that another person wrote by hand. I want to invite that challenge, and that pleasure, back into my cognition this year.

I’m not sure yet how to balance this with the convenience (and ecological prudence) of reading things offscreen without printing them out. Perhaps I can resolve to read on paper whenever I read for pleasure or whenever a book is assigned (and will purchase the physical book, rather than its Kindle rendition).

No comment yet, add your voice below!