Welcome to a new blog feature, in which I chat about a cool, unusual, or edifying bit from the daf yomi. Originating in the 1920, “daf yomi” is a Jewish learning regimen for the Babylonian Talmud, in which every day Jews from all over the world learn the same page. The Daf Yomi webpage, Hebrew text resource Sefaria, and many other resources can point you to the day’s page. I don’t always love this method–it can lead to speeding through some interesting stuff while spending more time on things that are less exciting–but I do find it appealing to be on a general calendar of learning with the rest of the Jewish world, across diverse denominations, beliefs, orientations, values, and methods.

One of the things that I find most appealing about Talmudic study is a logical approach to perennial problems of justice and ethics, and today’s page is no different. The last few days’ worth of pages find us in Tractate Sanhedrin, which addresses various law, adjudication, procedure, and evidence problems, which are of course of special interest to me. Pages 41-42 are concerned with issues involving evidentiary contradictions, the value and weight of testimonies, and issues involving last-minute halting of executions.

Readers who find this material crass might be comforted with the reminder that the Bavli is not an accurate historical record of criminal proceedings. Writings from the Second Temple era confirm the existence of the Sanhedrin, a high court within the Hasmonean empire and beyond (seated as a “big” Sanhedrin of 71 or a “little” Sanhedrin of 23–election proceedings dissected in the early pages of the tractate), but the extent to which it regularly issued judgments of life and death are dubious. The Talmud itself refers to the rareness of executions (saying that a Sanhedrin that ordered executions once every seventy years would be regarded as hovlanit, trigger-happy). By the time the Babylonian Talmud coalesces, it has been centuries since an actual Sanhedrin was convened, so a lot of this stuff is best understood as using scriptural anchors to elaborate on legal logic, rather than as a description of proceedings before real tribunals.

Anyway, Sanhedrin 42b turns to issues of executions, describing matters as follows:

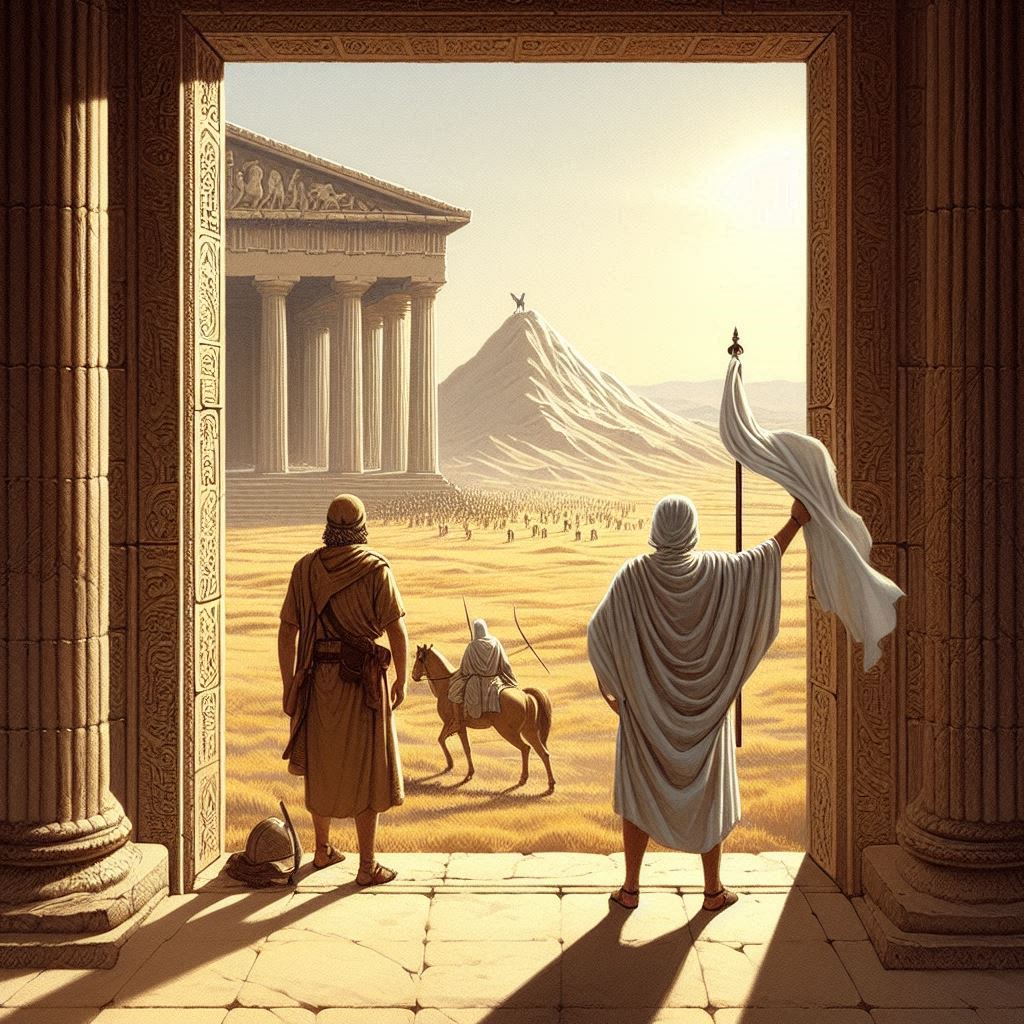

אֶחָד עוֹמֵד עַל פֶּתַח בֵּית דִּין, וְהַסּוּדָרִין בְּיָדוֹ, וְסוּס רָחוֹק מִמֶּנּוּ כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּהֵא רוֹאֵהוּ. אוֹמֵר אֶחָד: ״יֵשׁ לְלַמֵּד עָלָיו זְכוּת״, הַלָּה מֵנִיף בְּסוּדָרִין, וְהַסּוּס רָץ וּמַעֲמִידָן. וַאֲפִילּוּ הוּא אוֹמֵר: ״יֵשׁ לִי לְלַמֵּד עַל עַצְמִי זְכוּת״, מַחֲזִירִין אוֹתוֹ, אֲפִילּוּ אַרְבַּע וְחָמֵשׁ פְּעָמִים, וּבִלְבַד שֶׁיֵּשׁ מַמָּשׁ בִּדְבָרָיו.

One man stands at the entrance to the court, with cloths [vehasudarin] in his hand, and another man sits on a horse at a distance from him but where he can still see him. If one of the judges says: I can teach a reason to acquit him, the other, i.e., the man with the cloths, waves the cloths as a signal to the man on the horse, and the horse races off after the court agents who are leading the condemned man to his execution, and he stops them, and they wait until the court determines whether or not the argument has substance. And even if he, the condemned man himself, says: I can teach a reason to acquit myself, he is returned to the courthouse, even four or five times, provided that there is substance to his words.

This passage offers a few curiosities. Beyond the obvious drama of the whole thing, note that it is assumed that the folks inside the court will continue debating the matter of the convict’s guilt even as the convict has already been taken to the place of execution. Is this an academic issue for them, which merits continued discussion? Does it have to do with the previous issue of disagreeing about the contradictions between the prosecution’s witnesses? And how long does the horseback rider have to stand there waiting for the courtroom reporter, if you will, to come out waving the scarf? What happens if the court changes its mind, and the reporter desperately waves the scarf, but it’s too late? What happens if it’s not too late, but the horseback rider doesn’t see the scarf?

Another interesting thing about this passage is the implication that the execution takes place far away from the court. Much of the daf tries to find biblical anchoring for the distance from Moses-time justice, but there is also some commentary that suggests practical logic:

אִין, כִּדְקָאָמְרַתְּ. וְהָא דְּקָתָנֵי הָכִי, נָפְקָא מִינַּהּ דְּאִי נָפֵיק בֵּי דִינָא וְיָתֵיב חוּץ לְשָׁלֹשׁ מַחֲנוֹת, עָבְדִינַן בֵּית הַסְּקִילָה חוּץ לְבֵית דִּין, כִּי הֵיכִי דְּלָא מִיתְחֲזֵי בֵּית דִּין רוֹצְחִין. אִי נָמֵי, כִּי הֵיכִי דְּתִיהְוֵי לֵיהּ הַצָּלָה.

The Gemara answers: Yes, it is as you said, that the place of stoning was outside the three camps. And the practical difference from the fact that the mishna teaches the halakha in this manner is that if it happened that the court went out and convened outside the three camps, even then the place of stoning is set up at a certain distance from the court, and not immediately adjacent to it, so that the court should not appear to be a court of killers. Alternatively, the reason the place of stoning must be distanced from the court is so that the condemned man might have a chance to be saved, i.e., so that during the time it takes for him to be taken from the court to the place of stoning someone will devise a claim in his favor.

In other words, there are several reasons for setting the place of execution at a distance. One of them has to do with the optics of the court as a place of compassion. It’s not a nod at any modern notion of separation of powers; rather, it is the idea that associating adjudication with execution is unsavory and can lead to antipathy and, possibly, undermining of the court’s authority/legitimacy. The other one is precisely to facilitate the scarf-to-horseback method of postconviction review, which implies that people might still be working in the condemned’s interest even after the sentence is pronounced.

Having taught postconviction review and exonerations in law school, this stuff makes me think of the last-minute horrors that happen every time an execution approaches. Last-minute appeals, desperate litigation, petitions to the Governor, etc. Three years ago we marked a decade from the execution of Troy Davis, a man who many believe (and believed back then, as well) to be innocent of the crime. I remember collecting signatures to send to the Governor of Georgia to spare Troy’s life and holding a sit-in at my office about the case. In the years after Davis’ conviction, seven of the nine witnesses against him recanted, stating that they were subjected to police coercion, and persuasive evidence emerged that another man–the initial suspect–had committed the crime and, in fact, confessed to it. Not a shred of physical or forensic evidence connected Davis to the crime. We were unsuccessful and Davis was executed.

Even those saved by the “wave of the scarf” at the last minute have to endure disbelief, humiliation, and–when their compensation lawsuits fail–penury. One examples is John Thompson, who was convicted of a robbery and an unrelated capital murder in Louisiana; the crucial piece of evidence collected at the crime scene was a blood sample, which was never tested, and whose existence remained hidden from the defense for eighteen years, until a month before Thompson’s execution, when a PI working for the defense uncovered it. The blood did not match Thompson’s and he was exonerated. He was later unsuccessful in receiving compensation from the state, with the majority opinion claiming that no Brady violation had happened because the untested blood sample was not exculpatory evidence. Thompson wrote a searing op-ed to the New York Times about his experiences:

In 2005, I sued the prosecutors and the district attorney’s office for what they did to me. The jurors heard testimony from the special prosecutor who had been assigned by Mr. Connick’s office to the canceled investigation, who told them, “We should have indicted these guys, but they didn’t and it was wrong.” The jury awarded me $14 million in damages — $1 million for every year on death row — which would have been paid by the district attorney’s office. That jury verdict is what the Supreme Court has just overturned.

I don’t care about the money. I just want to know why the prosecutors who hid evidence, sent me to prison for something I didn’t do and nearly had me killed are not in jail themselves. There were no ethics charges against them, no criminal charges, no one was fired and now, according to the Supreme Court, no one can be sued.

Worst of all, I wasn’t the only person they played dirty with. Of the six men one of my prosecutors got sentenced to death, five eventually had their convictions reversed because of prosecutorial misconduct. Because we were sentenced to death, the courts had to appoint us lawyers to fight our appeals. I was lucky, and got lawyers who went to extraordinary lengths. But there are more than 4,000 people serving life without parole in Louisiana, almost none of whom have lawyers after their convictions are final. Someone needs to look at those cases to see how many others might be innocent.

If a private investigator hired by a generous law firm hadn’t found the blood evidence, I’d be dead today. No doubt about it.

A crime was definitely committed in this case, but not by me.

One only wishes that, rather than basking in the self-appeasement of having done no wrong, these officials, and those who worked with them, vigorously and unceasingly, desperately and demonstrably, waved the scarf so that any distant horseman, on any hill, would see them on time.

No comment yet, add your voice below!