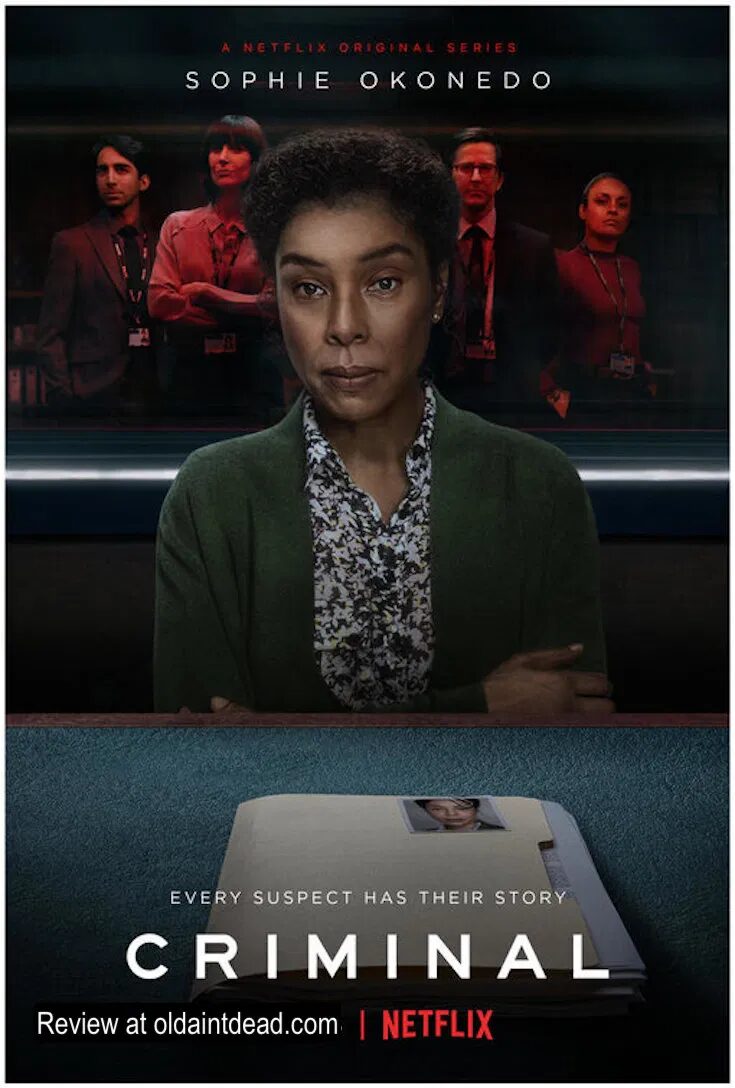

While out of the country, I got to while away the copious leisure time I didn’t have watching a fascinating international production: a Netflix series called Criminal. Four countries – the UK, Germany, Spain, and France – participated, each producing three episodes. The setting is very bare-bones: all four series utilize the same interrogation room with a one-way mirror in it. We see the interrogation of one witness or suspect, privy to what happens in the interrogation room as well as to what occurs behind the scenes. Some differences in procedure and legal culture are evident, but for the most part, it is a psychological drama.

In one of the Season 2 UK episodes, we see an interview with a woman named Julia, the ex-wife of a convicted murderer. Her ex-husband, who was a tutor for international students, apparently was involved with a young man from a foreign country and killed him. It now turns out that a second young international student is missing, and the team wants to figure out whether this young man met the same fate as the murder victim.

Julia has come to the interview on her own accord and appears very eager to help the interrogation: she is horrified by her husband’s deeds. It is a Sunday, and the team on the ground is sparse – just the interviewer and one more detective behind the mirror. But suddenly, the detective’s ears perk up: Julia has mentioned a few details about the peculiar method of the killings that were never released to the public; they were only included in the pathologist’s report, which she hasn’t seen. So how does she know?

The detective who is conducting the interview is, as of yet, unaware of this momentous fact. But the people behind the scenes are checking to make sure. The detective calls up the rest of the unit and, one by one, they arrive. They all seem to agree that, as long as the interviewer is unaware that Julia is incriminating herself, there’s no need to formally warn or charge her with a crime. It is only after the amicable interview is over and Julia exits the room that the commanding officer of the team approaches her, warns her, and places her under arrest. The following morning, she is interrogated under caution, and eventually provides more incriminating statements.

What if this had happened in the U.S.? That depends on whether the detectives were required to provide Julia with her Miranda warnings. It’s pretty easy to determine that, at the outset of the first interview, Julia is not in custody; she has come of her own free will to the station, she is collaborating, etc. As we know, Miranda warnings must only be provided to people under custodial interrogation; no custody, no Miranda requirement.

The more complicated question is whether the interrogating team’s awareness of the incriminating questions changes the nature of the interview into a custodial interrogation. By the time the team behind the mirror ascertains that only the killer could know the information Julia provided, it should be reasonably clear to them that she’s not going anywhere; she is the killer and, to top that, has framed her husband for the first murder. Does this change the constitutional status of the interrogation? Is Julia, at that point, in custody?

The definition of custody is: an arrest or its functional equivalent–a situation in which a reasonable person would feel that their freedom is considerably limited. Custody case law uses the suspect’s point of view: in at least one case, the suspect’s age is a relevant consideration as to whether they were in custody or not. Given that the actual interrogator in the room gives no indication that anything has changed (and is unaware of that herself), Julia doesn’t have any reasonable grounds to assume that her situation has changed. According to this view (and I suspect this is how many U.S. lawyers and legal scholars would see this), the warnings were unnecessary–which also means that the statements given during the second interrogation, in which she is given the warnings, are also admissible.

This does, however, raise the problem. If we say that Julia was not in custody during the first interview, we signal to detectives that there is an incentive for inviting people in as friendly witnesses and refraining from alerting them that their situation has changed. This is a fair argument in support of the idea that, once the interrogating team has become aware of the fact that the person is a suspect, rather than a neutral witness, they must give the person the warnings.

But that’s not the end of the story, because even according to this second view, while the first set of statements might not come in, the second one might. If the passage of time, the new warnings, and perhaps the added comment that the prior statements are inadmissible, count as curative methods, it’s quite possible that the statements from the second round will be admissible even if the first ones are not.

No comment yet, add your voice below!