Today’s entire page is devoted to the rules regarding the punishment of an adulteress, which the rabbis seem to discuss with great gusto. Even though, as I explained in previous pages, this crass conversation is academic for them and pursued for the exercise of logic, rather than for the actual fashioning of rules, it is still deeply jarring to be engaging in this. The rules this daf is concerned with can be found in Deuteronomy 22, which is everything you can expect from biblical punishment of women. To briefly summarize the biblical law:

- A man who falsely accuses his new wife of not being a virgin is to be flogged, fined, and forced to remain married to the woman;

- If the wife is truthfully accused of not being a virgin, she is to be stoned;

- If a man is found having sex with a married woman, both are to be executed (the method is unspecified);

- Same, but the woman is betrothed, not married, and the sexual encounter took place in the city: both are to be stoned (the logic: she did not cry out for help);

- Same, but in the field: only the man is to be put to death (the assumption is that the woman cried for help but was not heard);

- if two single people are found sleeping with each other, the man is to pay the woman’s father fifty pieces of silver and marry the woman.

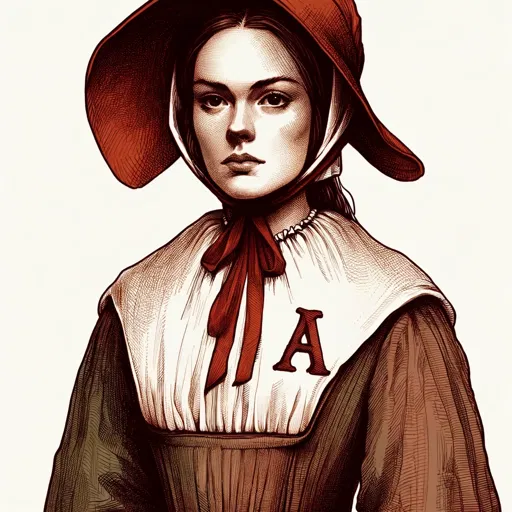

I should clarify right at the onset, this entire conversation, from Deuteronomy through the Baraita through the Bavli, revolting as it is, did not corner the market on the double standard of treating adultery as a crime. When Malcolm Feeley and I were looking at women and crime in Early Modern Europe, we did find plenty of evidence that adulterous couples were not treated the same; adultery tended to be one of the “typically feminine offenses”, like infanticide, abortion, witchcraft, nightwalking, and others, which were heavily enforced against women. Importantly, these offenses did not significantly skew the pattern of criminalizing women in the period and places we studied: the disappearance of women from criminal courts throughout the long 19th century reflects wider changes in criminal opportunities and in the public appetite for criminalizing women beyond these offenses. But that doesn’t change the fact that, as Nathaniel Hawthorne showed in his wonderful classic The Scarlet Letter, moralizing women and keeping them in line can explain a lot of what we see in adultery prosecution.

Incidentally, in case not everyone knows this, there still are U.S. states in which cheating on your spouse is a criminal offense. This map from Newsweek shows the places in which adultery is a misdemeanor in turquoise, and the places in which it is, astonishingly, a felony, in yellow.

All of which is to say: there is plenty to dislike in this daf, but the problem does not begin and end with the talmud.

Anyway, let’s get to it. There are two key distinctions that this page starts with: between a married woman and a betrothed woman, and between the daughter of a priest (בַּת כֹּהֵן) and a woman of ordinary birth (בַת יִשְׂרָאֵל). There are also some distinctions about the facts (who the other man was). The debate is whether a betrothed priest’s daughter should be stoned or burned, and whether a woman of any birth who slept with her father should be stoned or burned (hence the importance of the earlier debate on which death is the more severe punishment).

The gemara explains these differences of opinion thus: the rabbis, who believe stoning is the more severe punishment ascribe it to the more serious cases; Rabbi Shimon, who believes burning is the more severe one, does the opposite. This matters because you can’t kill someone twice: if two different death sentences are pronounced, only the more severe one must be carried out, so we need to know which one is the more severe one. And it also matters because within each category – married and bethrothed – there is the more serious case of the priest’s daughter and the less serious one of the ordinary woman. By contrast, perjured witnesses who blemish the reputation of a woman are killed in the same way (for a married woman, strangulation; for a betrothed woman, stoning) regardless of the woman’s status.

The next verses all play with different aspects of the offense and the offender’s identity, as mentioned in verses in Leviticus and Deuteronomy, to try and deduce which punishment applies. For example, whether the term כִּי תֵחֵל (who profanes) could apply to any priest’s daughter who violates Shabbat rules, or only to those who do so through promiscuity; whether this punishable promiscuity applies when the woman is single, or only when she is married; whether the term נַעֲרָה in some of these offenses refers specifically to an adolescent, a young woman, or to a priest’s daughter of any age; whether marrying outside of the priest caste rules a woman out of the “priest’s daughter” category (or perhaps marrying a non-priest is already an act of profanity); whether it makes sense to burn a woman for a transgression but use a different punishment for her accomplice. Lest this seem like silly gamesmanship, modern law revolves around the question of these loopholes just as well.

Consider, for example, the aftermath of Atkins v. Virginia (2002). In Atkins, the Supreme Court announced the substantive rule that people with “mental retardation” could not be candidates for the death penalty under the Eighth Amendment, but “le[ft] to the State[s] the task of developing appropriate ways to enforce the constitutional restriction.” Different states adopted different strategies, such as particular IQ cutoff points, or as functional tests of the person’s understanding of the criminal process, the sentence, and their culpability. Confusion continuously ensues, because there have now been numerous iterations of IQ testing, and the same individual could have different scores, or even test differently on the same test, and because psychological functional tests also morph over time. Generation after generation of legal interpreters–the legislature, the judiciary–have to wonder how to make the Atkins rule work in a variety of minute scenarios that were left unsaid in the original decision.

Or, for a closer example to the adultery case, consider the state of Wisconsin where, believe it or not, adultery is a Class I felony. The law states:

944.16 Adultery. Whoever does either of the following is guilty of a Class I felony:

(1) A married person who has sexual intercourse with a person not the married person’s spouse; or

(2) A person who has sexual intercourse with a person who is married to another.

The practical implications of this law are as slim as those of the biblical adultery rule: it is rarely enforced, and since Wisconsin is a no-fault divorce state, no one needs to call the police on their spouse for divorce proceedings. But you can imagine the theoretical discussion whether situations in which both parties are married should be treated differently, from a legal standpoint, than situations in which only one party is; or whether common-law marriage, which Wisconsin recognizes since 1917, can be the basis for adultery just like marriage in a wedding ceremony.

Still, there is something very discomfiting about thinking of guys who study currently at a yeshiva looking at this page today (as everyone who does a daf yomi in the Jewish world does), taking the discussion seriously, and then heading home to their mothers, sisters, girlfriends, and wives. Does even the theoretical discussion of this (mis)shape consciousness? And that’s before we’ve even come close to looking at Tractate sotah, which is full of stuff like this.

No comment yet, add your voice below!