I’m still very shaken by the news and find it difficult to engage with crass and violent materials, so today I’ll focus on the first portion of the daf, which deals with cursing offenses, rather than the second one, which analyzes sex offenses.

We start off with a reminder that Shabbat violations are punishable only when intentional, and move straight on to cursing. It’s an interesting transition: the end of page 65 was devoted to assorted witches, mages, soothsayers, etc., and shifting gears to cursing feels like the continuation of a grimoire.

Anyway, the mishna says that, to be liable for cursing one’s father and mother, one has to actually use a name; using a nickname incurs a liability according to Rabbi Meir, but is not an offense according to others. This is the point of departure for the gemara, which now breaks down the elements of the offense. First, they conclude that this is not just an offense for sons, but also for daughters or for any gender-fluid child (really, this is in the original). Then they wonder whether, to commit the offense, one must curse both parents. Rabbi Yoshiah thinks so, but Rabbi Yonatan thinks that either one is enough, because the text does not specify ״יַחְדָּו״ (together).

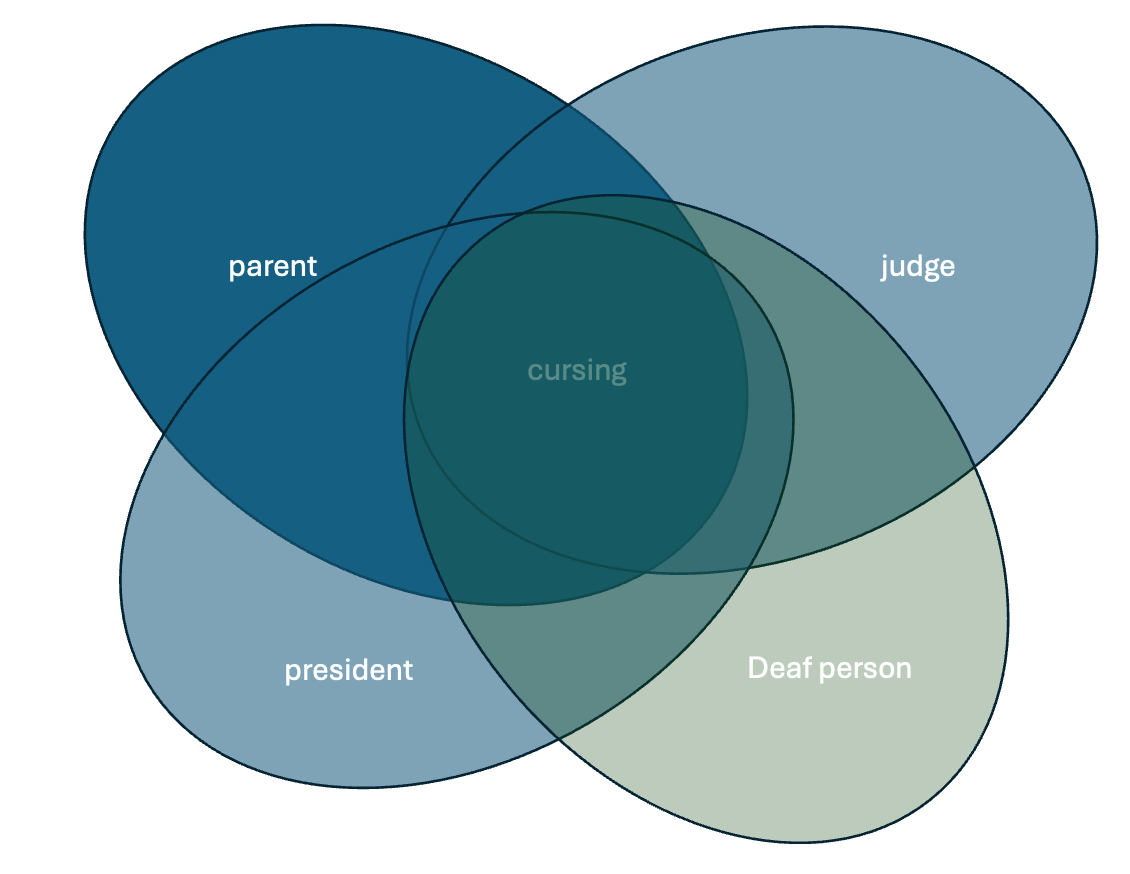

Here the gemara looks at several cursing offenses, which differ from each other in the target of the curse: God, a president, a judge, a parent. Here’s the debate:

״ תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״אֱלֹהִים לֹא תְקַלֵּל וְגוֹ׳״. אִם הָיָה אָבִיו דַּיָּין – הֲרֵי הוּא בִּכְלַל ״אֱלֹהִים לֹא תְקַלֵּל״, וְאִם הָיָה אָבִיו נָשִׂיא – הֲרֵי הוּא בִּכְלַל ״וְנָשִׂיא בְעַמְּךָ לֹא תָאֹר״. אֵינוֹ לֹא דַּיָּין וְלֹא נָשִׂיא, מִנַּיִין? אָמְרַתְּ: הֲרֵי אַתָּה דָּן בִּנְיַן אָב מִשְּׁנֵיהֶן. לֹא רְאִי נְשִׂיא כִּרְאִי דַּיָּין, וְלֹא רְאִי דַּיָּין כִּרְאִי נָשִׂיא. לֹא רְאִי דַּיָּין כִּרְאִי נָשִׂיא, שֶׁהֲרֵי דַּיָּין – אַתָּה מְצוֶּּוה עַל הוֹרָאָתוֹ, כִּרְאִי נָשִׂיא – שֶׁאִי אַתָּה מְצֻוֶּוה עַל הוֹרָאָתוֹ. וְלֹא רְאִי נָשִׂיא כִּרְאִי דַּיָּין, שֶׁהַנָּשִׂיא – אַתָּה מְצוֶּּוה עַל הַמְרָאָתוֹ, כִּרְאִי דַּיָּין – שֶׁאִי אַתָּה מְצוֶּּוה עַל הַמְרָאָתוֹ. הַצַּד הַשָּׁוֶה שֶׁבָּהֶם שֶׁהֵן בְּעַמְּךָ, וְאַתָּה מוּזְהָר עַל קִלְלָתָן. אַף אֲנִי אָבִיא אָבִיךָ, שֶׁבְּעַמְּךָ, וְאַתָּה מוּזְהָר עַל קִלְלָתוֹ. ״.

The issue is that there are separate prohibitions against cursing judges or presidents, and if one has a judge or a president for a father, one technically commits two offenses and, obviously, cannot be stoned twice.

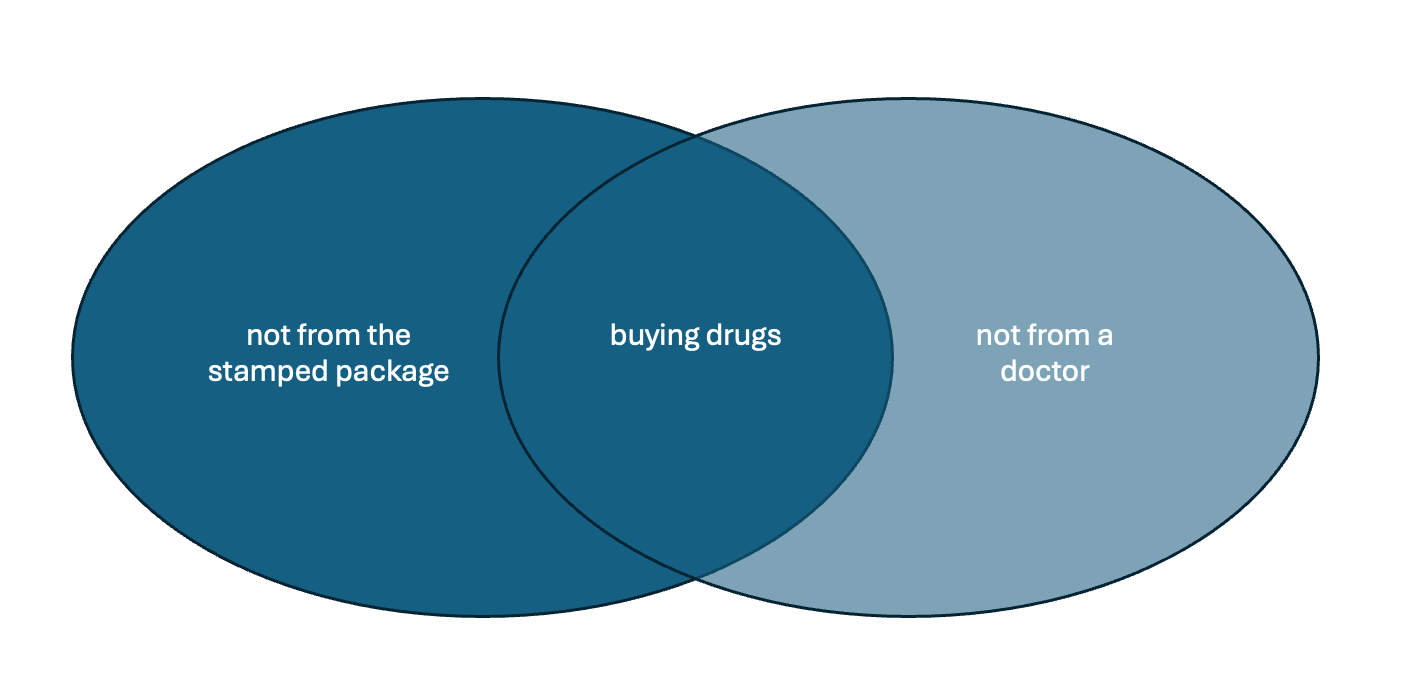

Remember Blockburger? The case that involved someone prosecuted twice for drug sales even though they were similar offenses and the buyer was the same guy? There was a second problem in Blockburger that raised legal issue, and it was this: The Harrison act prohibited buying drugs unless they came from a stamped package (which meant that taxes were paid for them; think buying recreational weed at a dispensary without a medical card), and it also prohibited buying drugs not from a doctor. Could the exact same purchase—if it was made from a non-doctor and not from a stamped package—furnish two counts or just one?

The disposition in Blockburger, which would later become the leading case on double jeopardy issues, was that it is okay to charge a defendant with two counts for the same action if each of the offenses had an element that the other did not:

The sages accept that the same principle applies in our case:

The sages then bring up another issue: the question of the social values promoted by these offenses. Technically, this is a classic Blockburger scenario: each offense has an element—an attribute of the victim—which the others do not. But these elements stem from the different nuances of respect you owe each of these three figures. And yet, they are all of your people, and respect is required for all of them. But in all these cases, one is expected to respect the victims’ authorities because of their greatness, which raises a fourth issue:

מָה לְהַצַּד הַשָּׁוֶה שֶׁבָּהֶן, שֶׁכֵּן גְּדוּלָּתָן גָּרְמָה לָהֶן? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״לֹא תְקַלֵּל חֵרֵשׁ״. בְּאוּמְלָלִים שֶׁבְּעַמְּךָ הַכָּתוּב מְדַבֵּר. מָה לְחֵרֵשׁ, שֶׁכֵּן חֲרִישָׁתוֹ גָּרְמָה לוֹ? נָשִׂיא וְדַיָּין יוֹכִיחוּ, מָה לְנָשִׂיא וְדַיָּין שֶׁכֵּן גְּדוּלָּתָן גָּרְמָה לָהֶן? חֵרֵשׁ יוֹכִיחַ. וְחָזַר הַדִּין. לֹא רְאִי זֶה כִרְאִי זֶה, וְלֹא רְאִי זֶה כִּרְאִי זֶה. הַצַּד הַשָּׁוֶה שֶׁבָּהֶן: שֶׁהֵן בְּעַמְּךָ, וְאַתָּה מוּזְהָר עַל קִלְלָתָן. אַף אֲנִי אָבִיא אָבִיךָ, שֶׁבְּעַמְּךָ וְאַתָּה מוּזְהָר עַל קִלְלָתוֹ. מָה לְצַד הַשָּׁוֶה שֶׁבָּהֶן, שֶׁכֵּן מְשׁוּנִּין? אֶלָּא, אִם כֵּן נִכְתּוֹב קְרָא: ״אוֹ אֱלֹהִים וְחֵרֵשׁ, אוֹ נָשִׂיא וְחֵרֵשׁ

The prohibition to curse a deaf person seems to have a different rationale: it is precisely because of the deaf person’s vulnerability—they cannot hear you, and therefore cannot protect themselves or respond to you—that cursing them is especially vicious. In that sense, it’s a prohibition of a different ilk than the previous ones. But the sages say: what all these people have in common is that they are מְשׁוּנִּין, they are unusual, there is something out of the ordinary about them that calls for special care or respect for them.

No comment yet, add your voice below!