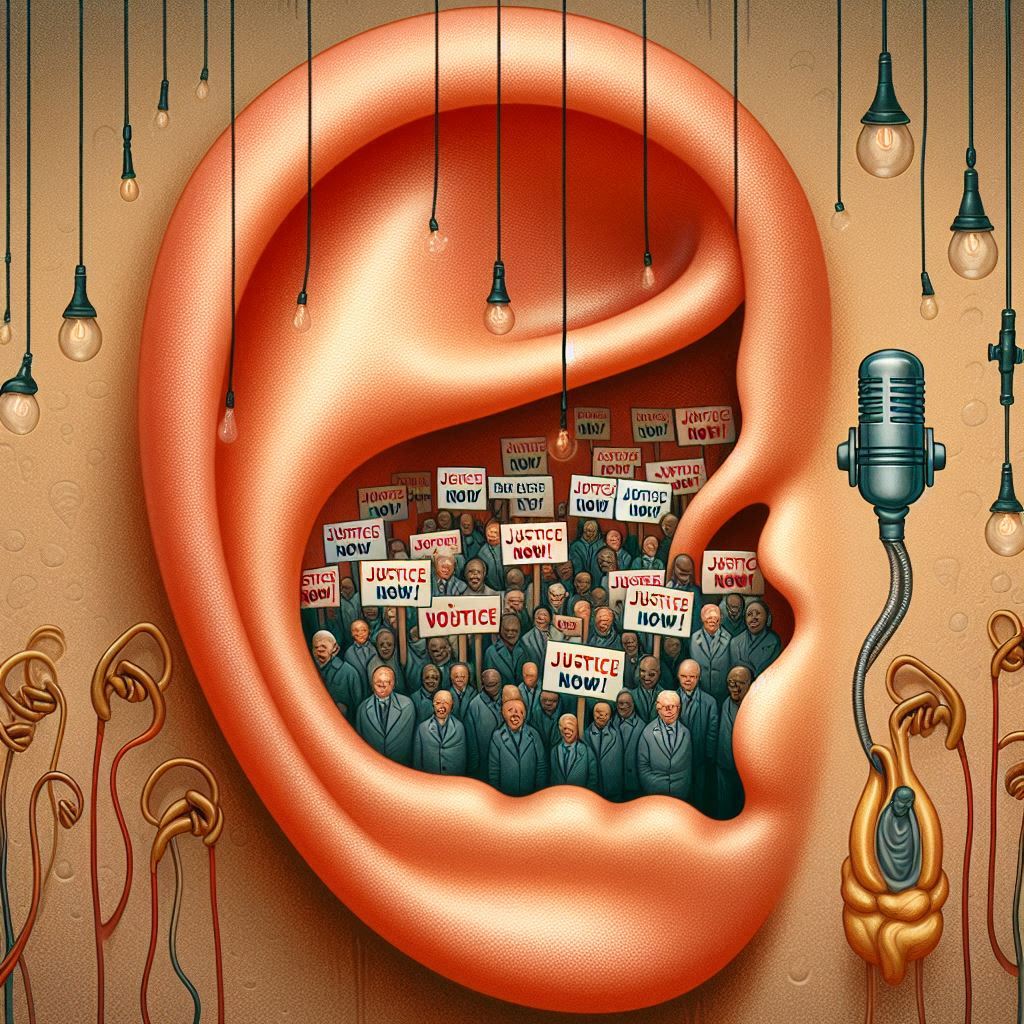

In my first post of this series, I set out to look at the interface between true-crime podcasts–an immersive medium, with democratized creatorship and potent suasion potential–and the criminal process, arguing that the increasing use of podcasts to galvanize public clamor for justice in cold cases and suspected wrongful convictions has not only benefits, but serious risks. I then presented three cases in which, despite (or because) the success of popular podcasts calling for justice, the criminal process either failed or was imperiled: Serial and Adnan Syed; Your Own Backyard and Paul Flores; Voices for Justice and Michael Turney. Examining these three cases, and a few others, has made me realize that there are several important ways in which podcasts and the criminal process are fundamentally incompatible; that these incompatibilities can hamper the criminal process; and that the proliferation of true-crime podcast affects these problems.

1. Compelling Facts vs. Admissible Evidence

What’s the most compelling way to prove something in an aural medium? To me, it’s an interview with a primary source, in which you can hear the facts from the horse’s proverbial mouth. Strong podcasts will include more such interviews, which is also ethical: some of the scandals in the true crime arena have involved allegations of plagiarism and misattribution. Unfortunately, what is a primary source in a podcast is an out-of-court statement, which cannot be offered at trial for truth of the matter asserted. On top of that, what makes for a willing, open interviewee–expressing empathy, rephrasing what the interviewee said, offering support–is the opposite of what might happen to the same interviewee on cross examination. While podcasters will sometimes fact-check interviews after the fact (e.g., ‘Ray said he wasn’t there. But we looked at the tape and he’s definitely in the picture”) or comment on the interview (e.g., “I’m not sure I believed Ray. He seemed evasive”), they rarely confront their interviewees on the spot the way opposing counsel would do at trial.

As to objects and forensics, one of the main problems with new media is the paucity of resources to test evidence and verify suspicions. Perhaps because physical evidence cannot be seen, only described, it invites readers to see it in the eye of their mind, and there it can acquire mythical proportions. Like many devoted listeners of the podcast Proof, which greatly contributed to the dramatic exoneration of Lee and Josh in Season 1, I was beside myself with excitement when, at the very end of Season 2–literally in the last few minutes of the last episode–Susan Simpson and Jacinda Davis, the podcasters, found the necklace of murder victim Renée Ramos, which had been lost in the courthouse and therefore never tested for DNA despite the high probability that it was the murder weapon. The suspect whose conviction the podcast revisits, Jake Silva, was Renée’s boyfriend, and when you think about it calmly, it is very likely that a DNA test will find his DNA on the necklace, which would not be probative at all in any direction; but calling attention to the object at a particularly dramatic point in the narrative and leaving the audience hanging with hope raises expectation that the necklace will turn out to be powerfully exculpatory evidence. Justice in the real world, though, moves very slowly, and it will take months before the necklace is tested.

There is also a selection bias that podcast audiences might not be aware of: cases are not randomly picked to be featured in podcasts. Rather, people who make their living producing immersive, engaging serial media select cases in which the personalities, artifacts, and primary auditory materials are compelling enough to draw attention and compete in what is becoming a very saturated market. What rates highly in garnering attention will not necessarily command the same power in a courtroom.

2. Dogged Pursuit vs. Acting within Constitutional Restraint

Anyone who has watched All the President’s Men, Spotlight, or She Said, has some appreciation for the dogged pursuit of sources and verifiable information that goes into a truly magnificent project of investigative journalism. The same things stand out in the podcast world: effort is a marker of quality. There is something very compelling about being invited on the bandwagon of an ongoing adventure, as opposed to hearing someone retell a story from cobbled secondary sources in the studio. Successful podcasts will evoke locations; Your Own Backyard host Chris Lambert is heard walking through the Cal Poly campus; Voices for Justice sees Sarah Turney speak to family members and friends about very sensitive issues; other podcasts, such as Counterclock and Proof see the hosts and producers knocking on doors and being rebuffed by witnesses and even by putative alternative suspects. It’s hardly necessary to point out that podcasters who pursue these encounters are taking on a not-inconsiderable amount of risk, and possibly requiring the police to take their safety into account. But the other important point is that many of these actions, which might be brazen for individuals, are not illegal (as long as they don’t cross the line into nuisance or harassment which, arguably, some do.)

The police, however, are not private people. Their actions are limited by the Fourth and Fifth Amendment. They have more powers than podcasters–they can search a person’s house–but using those powers requires adhering to constitutional limitations, like requiring certain levels of individualized suspicion and, sometimes, a warrant. I don’t think it’s an overgeneralization to say that podcasters tend to paint law enforcement with a negative brush, whether it’s a failure to solve a cold case or concerns that they railroaded the wrong person, but to assume failure to act requires understanding what hoops law enforcement is required to jump through before they act.

The issue of limitations and their absence pertains to the adjudicative phase as well. A podcast involving an unsolved crime or a wrongful conviction is an invitation to speculate about alternative suspects. How explicit that speculation is depends on the podcast’s approach, but a big part of the genre’s appeal is to encourage the audience to play with hypotheticals.

When investigating crime, of course, the police play with hypotheticals as well, but by the time a case gets to court, speculations are not usually encouraged. Indeed, sometimes there are constitutional limitations on speculation! Prosecutors are forbidden, for example, to draw the jury’s attention to the defendant’s decision not to testify (remaining silent is a Fifth Amendment right). Not every defense theory about an alternative suspect is going to be entertained by a judge (who has considerable discretion in compulsory process matters). Most defense strategies will shy away from speculating on an alternative scenario, and with good reason: all they need to do is poke holes in the prosecution’s story. Presenting a positive version of the events just invites poking holes in the defense story, which is not a jury trend the defense wants to encourage. Overall, then, criminal trials offer very limited room for speculation. Where podcasts open up the imagination, courts try to limit it as much as possible.

3. Taking Sides

A related wrinkle to the speculation issue is the question of how a podcaster wants to tell a story–namely, whether they’ll adopt an agnostic approach to the story and try on alternative scenarios for size, or position themselves ideologically on one side or the other. My impression of true-crime podcasts is that the better ones make an effort to seriously examine the weaknesses in the case even if they have a persuasive goal. Out of the three podcasts I’ve discussed here, Sarah Koenig’s Serial was the most agnostic one: even though Chris Lambert and Sarah Turney engaged in thorough investigation, both of them had a suspect in mind from beginning to end. But it is also important to say that Serial was followed by another podcast, Undisclosed, produced by Rabia Choudry, a lawyer and friend of the Syed family, which covers the same case but strongly advocates for Syed’s innocence.

What might be a virtue in a podcast advocating for justice can be a serious problem, for example, in prosecutorial discretion. I’ve argued elsewhere that some constitutional violations in criminal trials–most pronouncedly failure to disclosed exculpatory evidence to the defense–do not come from prosecutors who are being corrupt archvillains, but rather from people who have gotten too used to a way of thinking about a case that they develop tunnel vision and are unwilling to consider other possibilities. Because of this, I think that both prosecutorial offices and public defense offices should hire second-career folks who worked for the other side for a while, just to prevent calcified groupthink and introduce some flexibility and doubt into evidence assessment.

4. Outreach and Accessibility

This one is pretty obvious: the more viral a podcast goes, the better for the podcast–and, quite possibly, the worse for the legal case that comes from it. As Katrina Clifford explains in this beautiful, clear-eyed piece, a viral podcast can seriously contribute to contaminating a jury pool in ways that can be pretty insidious and go beyond individual jurors who listen to the podcast. As Clifford argues, podcasts have another important quality: they tend to generate communities of followers who become invested in a case over time, and whose conversations about the things that are front and center in their minds can spill over into other social contexts (as well as other media).

But there’s something else here that goes, I think, beyond what Clifford convincingly argues: the proliferation of true crime podcasts as a medium–not just the success of this or that individual podcast–in itself has an effect on how we see and address cases. It habituates people to think about criminal occurrences in a sensationalized, gossipy way, to speculate in wild directions, and to constantly share their opinions and impressions with others. To the extent that the demographic of podcast listeners (which is mostly female!) overlaps with the demographic of potential jurors, it invites a certain quality into jury deliberations that might override the care and adherence to the facts that jury instructions are supposed to encourage.

5. Context: When It Matters and When It Hampers

Finally, there’s the issue of framing. There’s a classic law and society article I really like, by my colleagues Austin Sarat and William Felstiner, called “Law and Strategy in the Divorce Lawyer’s Office.” In this article, the authors marshal evidence from 115 attorney-client conversations to show how the lawyers “legally construct” the clients, neutralizing issues that have tremendous emotional resonance for the clients and stripping complicated stories about failed relationships to the anodyne legal aspects that will be relevant. Law and Society scholars often complain about how the law keeps up appearances of disinterested neutrality, hiding the many ways in which the social and political context impact the outcome of legal cases. The law’s enterprise is to keep this context out; it’s seen as irrelevant to the determination of facts in an individual case.

Crime, however, doesn’t happen in a vacuum. How and why it happens, and how and why it is investigated (or not), is part of broader societal, cultural, and regional patterns. And many true crime podcasts are committed to placing crime within these contexts. Much of the democratizing effect of the platform is that women, people of color, and folks from other underserved demographics produce podcasts that seek to shine a light on crimes that suffer from lack of investigative energy and lower priorities (consider the “missing white female” syndrome issue that was so widely discussed during the media frenzy around Gabby Petito’s tragic murder). Whether or not justice is done, from a new media perspective, is not just a function of getting the facts right; it’s also a function of highlighting the broader context. I suspect that these broader sociopolitical trends were not insignificant factors in the Baltimore State Attorney’s decision to withdraw their support of Syed’s conviction–as well as in the subsequent administration’s decision to reopen the conversation and reinstate their confidence in the conviction. People who hope that the criminal process will not only provide some legal resolution, but also vindicate broader injustices and societal problems, are always going to be sorely disappointed with the outcome.

No comment yet, add your voice below!