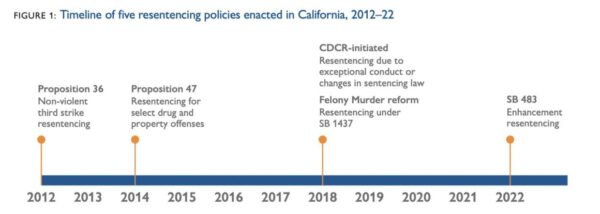

CalMatters, whose reporting on California prisons has been superb in the last few years, have a new article out by Cayla Mihalovich, which takes a look at the recent California effort to decarcerate and looks at who has been released. The article is based on a new report by Alissa Skog and Johanna Lacoe on behalf of the Committee to Reform the Penal Code, which you can read here in its entirety. The report finds that, in the last 15 years, 9,500 people have been released due to these policies:

The main findings of the report are:

Together, these five resentencing policies contributed to the release of

approximately 9,500 people. The number of people released under each

policy ranged from approximately 800 (CDCR-initiated resentencing) to nearly

5,000 (Prop 47) — with many people, especially those serving long sentences,

released earlier than they otherwise would have been.People released due to resentencing policies were less likely to be

convicted of new crimes within the first year than total releases, and

the majority of new convictions were for misdemeanors. The one-year

new conviction rates ranged from 3% (felony murder reform) to 29% (Prop

47). New serious or violent felony convictions were rare, with Prop 47 having

the highest rate at 1.6%.People resentenced and released after serving long sentences (a

median of 12–16 years) had very low recidivism rates. Among those

resentenced under felony murder reform, Prop 36, or CDCR-initiated

resentencing, just 3% to 8% were convicted of any new offense within one

year. Fewer than one percent — less than five people — released through

CDCR-initiated resentencing or felony murder reform were convicted of a

serious or violent felony in that time.Within three years following release, 25% of those resentenced under

Prop 36 were convicted of a new offense. More than half of those

convictions were for misdemeanors.Among those resentenced under Prop 47, 57% were convicted of a

new offense within three years, compared to 42% of total releases.

Thirty-eight percent were convicted of a new misdemeanor and 19% were

convicted of a new felony.Women made up a larger share of people resentenced under felony

murder reform than any other policy. Felony murder laws hold people

liable for deaths occurring during the commission of a felony, even if they

did not directly cause or intend the death. Women made up 11% of those

resentenced and released under felony murder reform, compared to 7% of

total releases. In contrast, women represented less than 2% of releases under

Prop 36 and SB 483, reflecting gender differences in arrests and convictions for

serious or violent felonies and sentencing enhancements.People resentenced under these policies were generally older and had

served longer sentences than all people released from prison in fiscal

year 2018–19 (“total releases”). Nearly 60% were aged 40 or older at

release, compared to 34% of total releases.

Mihalovich, who also read the report, gets straight to the point:

The report found low recidivism rates among people who were older and had served lengthy sentences. Those patterns contrasted with people serving shorter prison sentences for nonviolent crimes, which showed higher rates of recidivism, the majority of which were for misdemeanors.

The report, as well as my work on Yesterday’s Monsters, FESTER, and the many articles I wrote in between, have persuaded me of something that is plainly evident from the data but for some reason does not get nearly enough attention in criminological research: for all the focus on race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc., the factor that matters the most, by far, to (1) prison conditions (2) recidivism (3) quality of life (4) impact of prison conditions on healthcare outside prison is age. It is alarming to consider that, by 2030, one in three (!!!) prisoners in California will be over the age of 55. Through years of focusing our attention on releasing younger people serving short sentences for nonviolent crimes (which do not necessarily reflect the person’s actual criminal activity), we have turned our prisons into geriatric facilities. The number one surprising fact that my students always share after visiting people in prison is “how old everyone is.” Age is also the one factor that has been robustly found, throughout decades of research in life course criminology, to predict crime rates.

Despite how obvious this is from the data, I don’t think this crucial fact is known or properly appreciated by the public. Moreover, it is not appreciated even within CDCR, which has the most experience dealing with people of various ages. Any parole agent will tell you (and several said so in places where I did fieldwork for YM) that the easiest, most level-headed, calming, and most sensible people they deal with are released lifers who, by nature of their crime of commitment, have spent long years behind bars and are thus in their fifties and over. But when CDCR initiates resentencing, as the report shows, they are shy to release members of this group. Their own risk assessment tool defies what they see and experience every day from these prisoners: they accord disproportionate weight to the crime of commitment, even if that crime happened decades ago. Even when age impacts not just propensity to reoffend, but also serious risk of sickness, hospitalization, and death–such as in the COVID-19 years–the release policies do not prioritize the 55-and-over group. And even though the chief expense on incarcerated people is their healthcare, it does not fully dawn on us that the group with the most expensive healthcare and the least risk should be first in line for releases. The one exception, as the report shows, is the fiscal year 2018-2019, and it is shocking to me that this did not continue in 2020-2021, when this policy would make the most sense.

A related inconvenient truth is that Prop 47, which is loudly decried and loudly defended by opposing political camps, ended up not being the wisest investment from a recidivism standpoint. As I explained in Cheap on Crime, the postrecession renaissance for justice reinvestment, which led to the reversal of the mass incarceration trend for the first time in 37 years, had to rely in many states on bipartisan agreements, and it was easier to agree on low-hanging fruit: nonviolent drug offenders, then perceived as the group to whom our incarceration policies were most unfair. In California, where bipartisan support was not necessary, there was nevertheless a focus on this group because its incarceration tends to be associated with racial discrimination. But the numbers speak very clearly: younger people convicted of nonserious offenses are more likely to recidivate than older people convicted of serious offenses long ago.

Obviously, there are other factors beside risk that go into the sentencing calculus. Serious, violent, even heinous, crimes evoke an understandable public outcry and, for people who believe that punishment should reflect the severity of the offense and serve a retributive purpose, reluctance to release older people serving long sentences is a function of wanting these long sentences to reflect our moral recoil from homicide, rape, kidnapping, etc. But given how long these sentences are–the average person now spends 28 years in prison before being paroled, and this data point is misleading because it includes people who have not yet been paroled–we have to ask ourselves whether or not we believe in atonement at all.

And if the most “bang for our buck” involves the utilitarian function of punishment–reducing the propensity to reoffend, whether through deterrence or rehabilitation–age is and should be a factor. People in their fifties, sixties, seventies, and eighties do not recidivate not because they’ve been “scared straight” or because they’ve “reformed” but because they have simply aged out of crime. This is a politics-neutral fact that we have to accept and must make the cornerstone of our resentencing/release/parole policies.

No comment yet, add your voice below!