In Behind Ancient Bars, law professor and rabbinical student Hadar Aviram challenges the conventional assumption that incarceration is an artifact of modernity by looking back to depictions of detention and confinement in the Hebrew Bible. Aviram takes readers on a journey through the Hebrew Bible’s carceral landscape through creative rereadings of five stories: Joseph in Egypt, Esther in Persia, Daniel in Babylonia, Samson in Gaza, and Jeremiah in Jerusalem. Drawing on her experience as a leading voice against mass incarceration, she finds connections between antiquity and the contemporary understanding of incarceration that encompasses not just the prison itself but also pretrial/immigration detention, bail, electronic monitoring, parole, and postrelease supervision. Infusing ancient biblical stories with fresh life through modern punishment theories, Aviram shows how incarceration has much to teach us about government, the experience of people in confinement, and the strength and resilience of the human spirit across millennia.

Death Penalty Resurrections

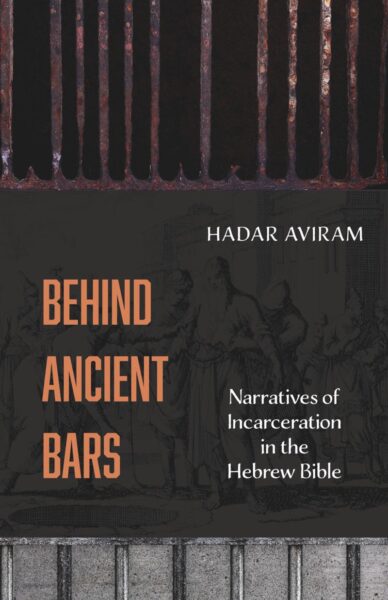

I used to believe, like many in the criminal justice research community, that once a country gets rid of the death penalty, it never returns (which is why I saw as a welcome development its slow demise in the U.S.). And this is still true–for the most part. It’s certainly true for the bulk of Western industrialized countries that abolished the death penalty between the 18th and the early 20th centuries. There are, however, some examples to the contrary. At the moment, there is a proposal brewing among some of Netanyahu’s cabinet ministers (chief among them, of course, convicted terrorist Itamar Ben Gvir, now the minister of police) to bring back the death penalty for acts of terror (one of them helpfully added that Jews could be executed, too). Because the situation in Israel is so unstable, it’s easy to see this through an exceptionalist lens. But is that really the case?

In starting to think about this, I have three hypotheses:

- Death penalty resurrections are, indeed, rare.

- When the death penalty does come back, it’s usually through a combination of the following three interrelated conditions: (a) a heinous “redball” crime, alongside with a true or perceived rise in violent crime; (b) a serious conflict between governmental powers, with the executive and legislative powers on one side and the judicial on the other; (c) a groundswell of punitive public opinion and the sentiment that courts do not properly represent/affirm public sentiment.

- The resurrected death penalty is marketed and legislated as applying only to a specific category of particularly heinous crimes, which later become “gateway crimes” and pave the path to its application in less serious cases.

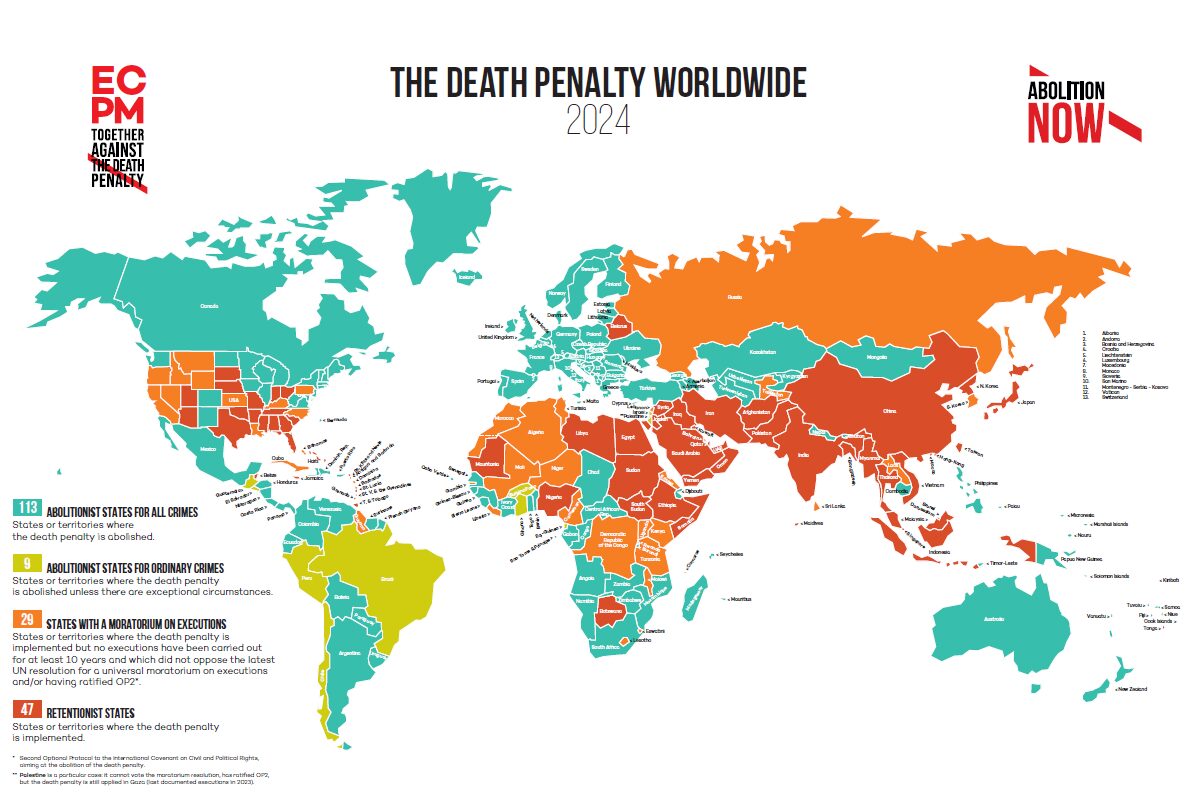

The first country worth a careful examination is, of course, the U.S., because its slowly dying death penalty is considered a “peculiar institution” when compared with Western industrialized countries. When punishment researchers look at the moratorium years (which started in 1972 with Furman and ended in 1976 with Gregg) they tend to read Furman very narrowly. After all, Furman did not say, as its Californian counterpart People v. Anderson did, that the death penalty was barbaric or immoral; all it did was find fault with the wide discretion in its application. I think this reading of the case is true to the language of the case, but it is anachronistic regarding its massive impact. As I explained in Yesterday’s Monsters, by the time Anderson was decided in CA and Furman in D.C., public support for the death penalty had already been on the rise again, arguably because of the rise in serious crime, which was one of the lynchpins of the Nixon presidential campaign.

When the death penalty returned to the U.S., in the form of Gregg-compliant state statutes and constitutions, it was limited to certain types of crime. Under these schemes, the death penalty would only apply to murders and other serious crimes exhibiting enumerated aggravating circumstances. But actual executions have been sporadic, even in “killer states” (with the exception of the Trump federal execution spree in 2020: 10 executions). To the extent that Furman should be read more broadly, this confirms my first two hypotheses but not the third one.

Is the U.S. unique? In contrast with the usual comparisons to industrialized Europe, Malcolm Feeley has argued that the more appropriate criminal justice comparison is to South American countries. Building on insights from American Political Development (APD), Feeley argues that the U.S. and South America share the following four characteristics: (1) A legacy of serious ethnic conflict, including slavery; (2) widely available firearms; (3) considerable political corruption; and (4) a high rate of interpersonal violence.

A few years ago I wrote an article about U.S. influences on Israeli criminal justice policy, in which I argued that developments in policing, courtroom proceedings, and sentencing in Israel closely track U.S. developments, because the two countries actually share these factors. In other words, the U.S. is not a role model because of its criminal justice excellence, but rather because of its sociopolitical characteristics. This suggests to me that other countries in which the death penalty was resurrected are worth examining.

The Philippines abolished the death penalty through their Constitution in 1987, but reinstated it in 1993 via legislation (Republic Act 7659). The legislative initiative was the fruit of President Fidel Ramos’ election campaign, which was buoyed (or exploited) public demand for tough-on-crime measures due to rising crime rates. Capital punishment, under the new law, would only apply to “heinous crimes,” which was a loophole in the 1987 Constitution, and seven executions were carried out until it was abolished again in 2006 by law.

In Pakistan, a six-year death penalty moratorium was lifted in December 2014 following the Peshawar school massacre (horrific Taliban terrorist attack of a school, which resulted in 150 deaths). Resuming executions was a response to public outrage about the massacre, and initially, the moratorium was lifted only for terrorism-related cases. However, only three months later, the moratorium was expanded beyond terrorism, and executions continue to occur in Pakistan for various offenses beyond terrorism.

Brazil’s death penalty was abolished in 1891, but then reinstated in the years between 1938 and 1953 for cases involving terrorism or subversion considered “internal warfare”. The reinstatement coincided with a shocking coup d’état and the Estado Novo dictatorship, and the abolition with a rail disaster and with Brazil’s legislative election. During a time of military dictatorship, which began in 1969, Brazil reinstated the death penalty for political crimes resulting in death; the death penalty was fully abolished for non-military offenses in the 1988 Constitution. Both reinstatements were executive/legislative actions during authoritarian input, and no actual executions were officially recorded during these times (the military dictatorship killed at least 300 opponents extrajudicially during this pedior, though).

Nepal abolished the death penalty for ordinary crimes in 1946 but brought it back in 1985 through legislation for murder and terrorism. The death penalty was fully abolished, through a Constitutional prohibition, in 1990. Executions did not occur during the reinstatement period.

Sri Lanka’s last execution occurred in 1976, but after the assassination of High Court Judge Sarath Ambepitiya in 2004, and generally a surge in violent crime after the end of the civil war, there was a public outcry to end the moratorium. The 2004 reinstatement was announced for rape, drug trafficking, and murder, but no executions were carried out. In 2019, President Maithripala Sirisena signed several death warrants, but no executions have occurred yet.

The special conditions in each of these countries makes it difficult to compare them, but a few insights about my original hypotheses emerge:

- These are indeed rare occurrences. In most of the world, once the death penalty goes away, it never comes back. But the U.S. is only exceptional if compared to Western industrialized countries, when it does share some important sociopolitical characteristics with some of the countries on this list.

- Looks like my second hypothesis was true. In all of these cases, the reinstatement of the death penalty happens following a “redball” crime or a perceived dramatic uptick in serious crime, and except in Brazil, where the whole thing happens with no democratic input, it is supported by punitive public opinion. Importantly, when the death penalty does go away, it’s often through a judicial act.

- My third hypothesis seems only partially supported by the data. The return of the death penalty is usually promised to apply only to specific, heinous categories of crime. However, contrary to my hypothesis, it doesn’t necessarily lead to an expansion of the categories. The one outlier is Pakistan, which shares an important feature with Israel: the return of the death penalty is marketed as a response to a horrific, terrorism-related mass murder.

At some point in the near future I want to take a closer look at additional countries in which the death penalty has not been reinstated but which evince a strong popular movement to reinstate.

Evolving Standards of Cult Perceptions

A new story in the New York Times offers an overview and a behind-the-scenes look at a new seven-episode podcast featuring Allison Mack, Keith Raniere’s second-in-command in the NXIVM cult. Raniere, you’ll recall, received a 120-year prison sentence for his horrific crimes, which included sexual enslavement and fraud.

Mack has recently completed 21 months of a three-year sentence, which she started while still in thrall to Raniere and the cult. What is striking about the article is how nuanced the writing (and the interview with the podcaster, Natalie Robehmed) are regarding Mack as a person whose perspective is worth investigating:

“I think what I told Vanessa was, ‘I have no interest in being a part of Allison Mack’s redemption arc,’” Robehmed recalled. “The only version I knew of her was the one who’d appeared in previous coverage and documentaries — Allison Mack: The Villain.”

But at a dinner in Los Angeles with Mack and Belber, Robehmed found the actress to be introspective and remorseful, unguarded when it came to acknowledging the pain she had caused women below her rank in NXIVM, some of whom she pushed to seduce Raniere, send him nude photos and brand his initials on their flesh.

Mack told Robehmed she had no intention to return to acting — or to participate in any media apart from the podcast — and was pursuing a degree in social work. (Through a representative, she declined to comment for this article.) Last summer, Robehmed accompanied her to get her own NXIVM brand covered by a tattoo.

In the podcast, Mack is blunt about her guilt.

“I was aggressive and forceful in ways that were painful for people, and did make people feel like they had no choice, and was incredibly abusive for people, traumatic for people,” she says, when asked by Robehmed about her reputation as a particularly ruthless lieutenant of Raniere’s. “One hundred percent, all those allegations are true.”

That Mack is sincere and apologetic about her part in the cult does not, of course, ameliorate her guilt or the severity of the crimes she committed. But we have the benefit of examining her story in 2025, when we already have a fairly sophisticated understanding of cults, brainwashing, and mind control. This was not the case during the Manson family trials; as I explain in Yesterday’s Monsters, in 1971, when the trials took place, the kind of mind control that characterizes cults was something that was attributed, culturally, to communist countries and their psychological abuse of American POWs (e.g., the Manchurian Candidate). It was only in 1973-1974 that parents of the many people swept into cults in the late 1960s and early 1970s prompted the California legislature to hold hearings about the phenomenon. I talk a bit about all that in this post (and, of course, in the book). I don’t think that the Manson women–who were teenagers and adolescents at the time of the murders–would have gotten off scot-free, even today. But I do think that the nuanced perspectives that we see in the Mack case would have made a difference, if not in the initial sentencing, then certainly on parole.