In case the horrific damage Trump and Trumpism have done to our democracy was not obvious from the horrendous crimes in plain view of the last few days (or the last four years, including human rights crimes masquerading as policies) today we have evidence on the local level of how deeply the notion that democracy can be purchased and toyed with has resonated with some Silicon Valley dolts. Not that these people needed Trump’s encouragement to think of San Francisco as window dressing for their lives, and of all of us as “local color” providing a picturesque setting for their VC deals. But today really takes the cake with an idiotic fundraiser, organized by this guy, who seems to think that his claim to virtue–being ridiculously and ostentatiously rich in a city where other members of the human race have to starve, defecate, and die in the streets–is a proper substitute for actual criminal justice expertise.

This initiative comes in the heels of a horrific tragedy–a fatal car accident that claimed the lives of two women. The man behind the wheel, Troy McAlister, was intoxicated and driving a car he had stolen from a date. Because Chesa Boudin ran on a progressive prosecutor platform, the focus is on prosecutorial missteps that led to McAlister being free: before this recent crime, he had been headed toward trial in late 2018 on two counts of second-degree robbery in connection with a 2015 holdup in a San Francisco store. Boudin’s office “referred these cases to parole because we believed there was a greater likelihood of him being held accountable and having the kind of intervention that would protect the public and break this cycle of recidivism.”

Since I know something about parole, I can explain that there are two ways in which people on parole end up back in prison: either they commit a new crime, for which they are prosecuted and tried (this can take months, if not years) or they commit a parole violation that lands them back in prison. Oftentimes, there’s an overlap. While some parole violations are technical and trivial, others amount to new crimes. It is not unreasonable to think that a parole violation route will be more efficient than a new prosecution, though things have somewhat changed in terms of the implications. Before the Schwarzenegger Administration’s parole reform, parole violators pretty much automatically ended back in prison, even for very minor violations–resulting in a prison population comprised of 50% of the people doing time not for new crimes, but for parole violations. The reform, aimed at alleviating the obscene 200% overcrowding in the system, aimed to give parole agents more discretion and a range of intermediary sanctions before throwing them back in the slammer, depending on discretion and on how severe the violation was and how risky the person was judged to be.

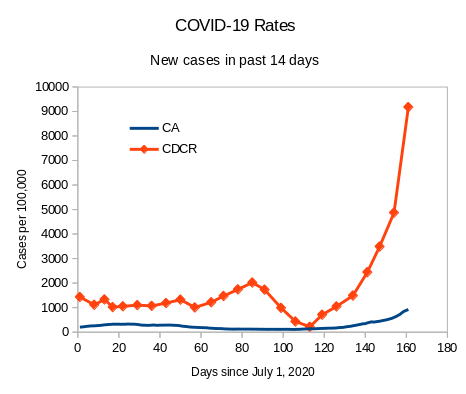

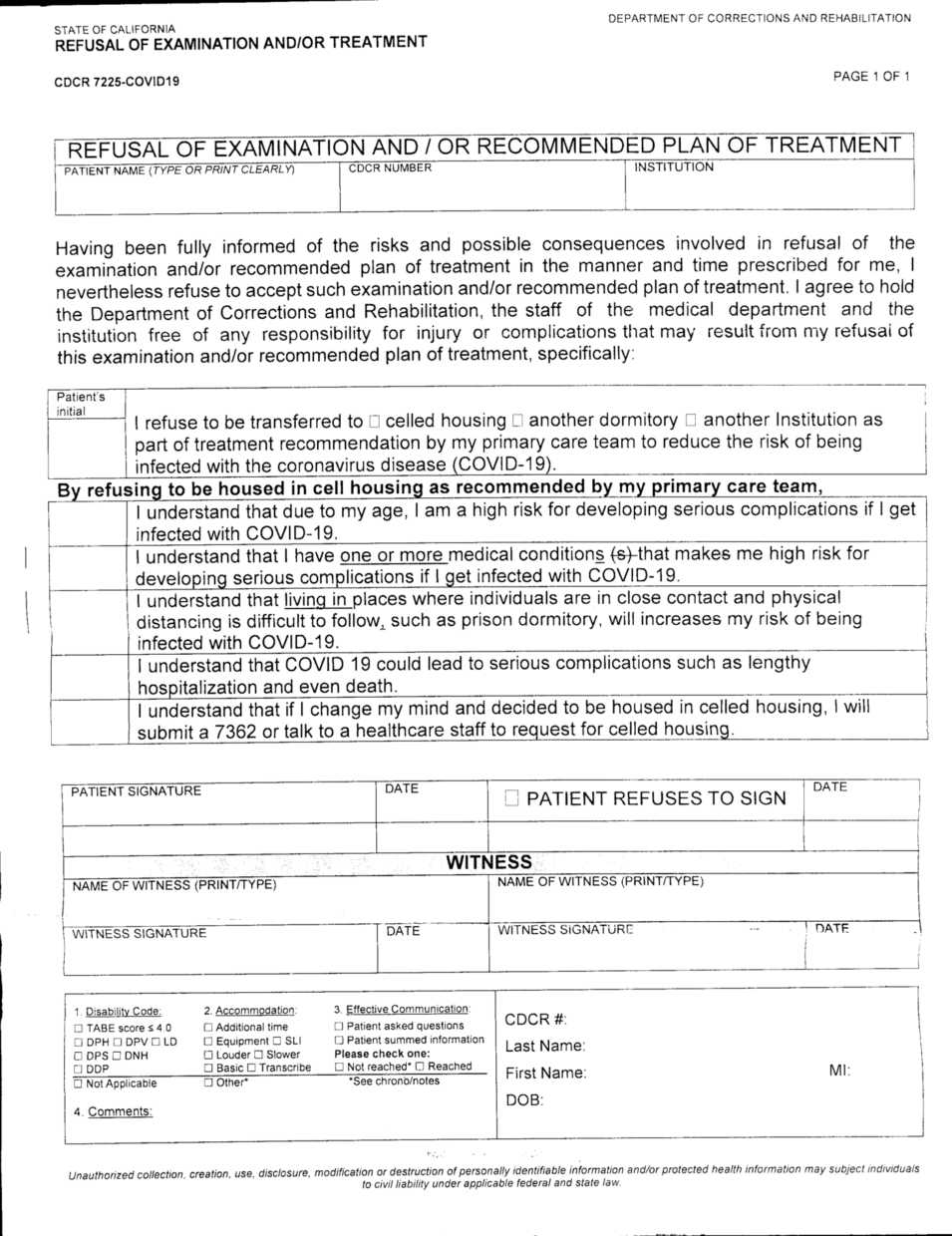

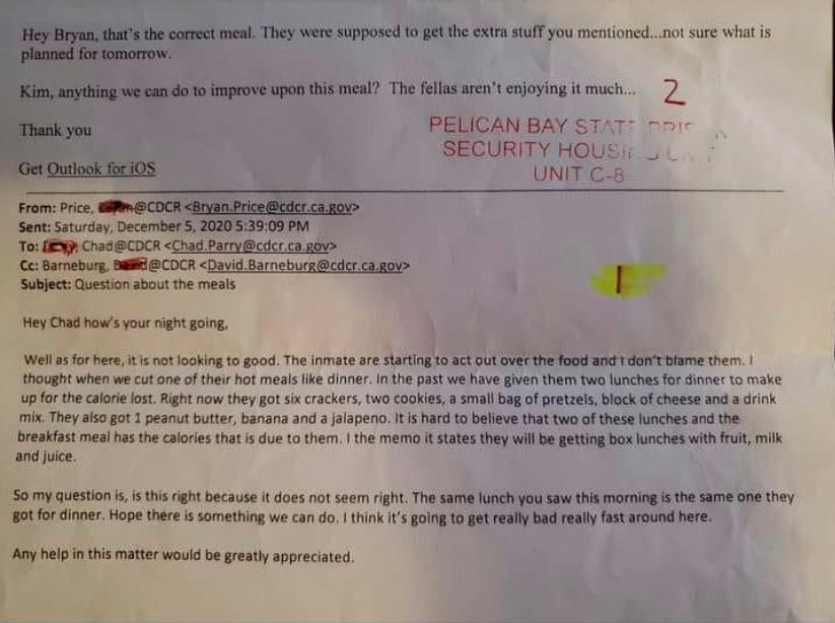

Like any situation involving risk prediction, when deciding whether to remand a person to CDCR or use an intermediary sanction, parole agents could be right or they could be making one of two types of mistakes. False negatives are situations when the person is assumed to not be much of a risk but then commits a new crime (such as McAlister). False positives are situations where a person is kept behind bars, mistakenly perceived as a release risk, when had they been released, they would not have committed a crime. Obviously, we only hear about false negatives, not false positives, because they appear to be penalty-free. But false positives also have a grave price. As of today, 133 people have died of COVID-19 behind bars. Most of those people were aging folks, who are largely assumed to have aged out of crime, and who would have posed no danger to the outside world had they been released (which would have saved their lives.) Their illnesses and death, in turn, resulted in infections, illnesses, and deaths in the communities surrounding the prison. It’s just that our society is not particularly inclined to value the harm and price paid by these people and their families as we value the lives on the outside. But any time we make a judgment call about risk, we might be making either mistake. And that means that some mistakes, which are horrible, and tragic, and senseless, and enraging, cannot be prevented. This is a horrible truth to live, but it doesn’t necessarily indicate that there’s something systemically wrong at the prosecutor’s office or at the parole agent’s office. It indicates that someone made a horrible mistake.

Moreover, our attention to particular instances of false negatives blur their overall context. Every fatal traffic accident that happens in San Francisco, of which there are dozens every year, leaves a deep wound of grief in its aftermath. Many of them are as preventable as this one. And the vast majority of them never make the news, because they don’t involve parolees, which is why we deal with them through initiatives such as Vision Zero, rather than through hatchet jobs against our elected officials.

So why are we making this horrific tragedy into a cause célèbre? Because there are political hatchets being forged, such as this “astroturf fundraiser” (as my friend Chris Johnson called it), about which there isn’t much to say that isn’t obvious. However, obscene wealth seems to make people impervious to the obvious, so here it is: It turns out that we have a magical and effective mechanism in the United States for holding prosecutors “accountable to the people.” It’s called voting. The people wanted a progressive prosecutor and, should they be displeased, they can elect someone else. Voting comes in pretty handy in procuring accountability, because it is available to people who have less money than Mr. Calacanis. The funny thing is that, throughout the last decades, because of aggressive fearmongering propaganda, voting regularly and reliably produced aggressive prosecutors who almost singlehandedly drove our mass incarceration crisis. Now, we’ve been through the 2008 financial crisis, and the Obama administration, and the horrors of Trump and a second recession, and the American public has apparently come to the conclusion that they are ill served by this sort of prosecutorial policy, and so they are choosing something else.

Mr. Calacanis knows this, of course. He and his ilk have been more than happy with this system as long as the hoi polloi reliably voted for the kind of prosecutors they like, but democracy doesn’t suit them quite to the same degree when the plebeians want social services, relief from cash bail, a wrongful convictions unit, and humane jails. So when he claims to speak for “the people,” he is not championing you and me–he’s championing his rich buddies, whose favorite pastime is to abuse and exploit California’s delicate democracy and treat it as a playground for their contemptible ideologies and ridiculous experimentation. This is not a particularly original move. Calacanis is merely following in the footsteps of several folks just like him, like the wealthy guy who gave us Marsy’s Law (which we have to blame for having so many old and sick people behind bars, denied parole in the face of COVID-19 for no logical reason) or the clown who wanted to split California into six states. It should also come as no surprise that these folks believe that investigative journalism, just like democracy, is something you simply buy with Silicon Valley money–even though we have excellent investigative journalists at the San Francisco Chronicle who are all over this story and are not for sale.

Look, I’m not an idiot. I know that politics-for-sale is festering throughout this great nation, and I cling to my youth in Israel, where that was not the case to this depraved degree, mostly for sentimental reasons. I know that the social democracy in the Old Country breathes no more, but its memory and ethos live on, and I have daily proof that even that faint memory works better than than the corrupt, unbridled capitalism of the U.S., in the form of people from my age cohort in Israel posting pictures of having received the vaccine I can only dream about. I remember being physically nauseated when I read the Mueller report, partly because it gave me a window into the lives of oligarchs who think nothing of buying caviar for $30,000. Mr. Calacanis and his buddies are obviously not as rich as their Russian counterparts (that must sting,) but they’re trying to play the same game. And it is universally loathsome, regardless of whether the perpetrators wear ostrich jackets or Patagonia fleece vests.