When I heard late last night of Gov. Newsom’s decision to close California beaches because of crowds, I was devastated. I observed my thought pattern immediately cycle through the first three of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief: denial (“I can’t believe this. It can’t be happening. Surely this won’t happen”), anger (at the Governor, at the mayor, at the lawmakers, at the folks congregating in five SoCal beaches – “you are why we can’t have nice things!”) and depression (“what am I going to do? How will we get through this month?”). This morning I progressed to the bargaining stage (“wait, he said state beaches, right? So SF beaches, which are run by the city, are exempt, right?”) and I might find some acceptance later this afternoon.

In short, my inchoate fear, sadness, and uncertainty, finally found an appropriate coathanger to hook itself to, and I was in emotional turmoil throughout the night.

Now that the emotional storm has passed, I’m thinking a bit about what park and beach closure policies have to teach us about the punitive and cooperative aspects of making public policy. Oftentimes when prohibitive legislation is considered on any topic, ranging from speed laws to tax policy, people forget that any policy brings with it some level of noncompliance. A classic article by Fred Coombs provides a typology of reasons for noncompliance: “(1) lapses or ambiguities in communication; (2) insufficient resources; (3) an objection to the policy itself (i.e., its goals or its assumptions); (4) distaste for the action required; or (5) doubts about the authority upon which the policy is based, or that authority’s agents.”

Looking particularly at (3) and (4), which are different facets of how much one agrees with the policy decision and how much one is inconvenienced by them, reminded me of Tom Tyler’s classic work Why People Obey the Law. Moving away from the “instrumental” explanations (“people obey if there’s something in it for them”), Tyler focuses on normative ones, which are concerned with–

the influence of what people regard as just and moral as opposed to what is in their self-interest. It also examines the connection between normative commitment to legal authorities and law-abiding behavior.

Tom Tyler, Why People Obey the Law, pp. 3-4

If people view compliance with the law as appropriate because of their attitudes about how they should behave, they will voluntarily assume the obligation to follow legal rules. They will feel personally committed to obeying the law,

irrespective of whether they risk punishment for breaking the law. This normative commitment can involve personal morality or legitimacy. Normative commitment through personal morality means obeying a law because one feels the law is just; normative commitment through legitimacy means obeying a law because one feels that the authority enforcing the law has the right to dictate behavior.

According to a normative perspective, people who respond to the moral appropriateness of different laws may (for example) use drugs or engage in illegal sexual practices, feeling that these crimes are not immoral, but at the same time will refrain from stealing. Similarly, if they regard legal authorities as more legitimate, they are less likely to break any laws, for they will believe that they ought to follow all of them, regardless of the potential for punishment. On the other hand, people who make instrumental decisions about complying with various laws will have their degree of compliance dictated by their estimate of the likelihood that they will be punished if they do not comply. They may exceed the speed limit, thinking that the likelihood of being caught for speeding is low, but not rob a bank, thinking that the likelihood of being caught is higher.

Tyler thinks that that fostering compliance from a normative place works better because it requires less enforcement and it fosters more care for people’s values and motivations. He coins the concept “procedural justice” to argue that, when people think a decision has been made fairly–even if it disadvantages them personally–and they have been treated respectfully, they are more likely to comply.

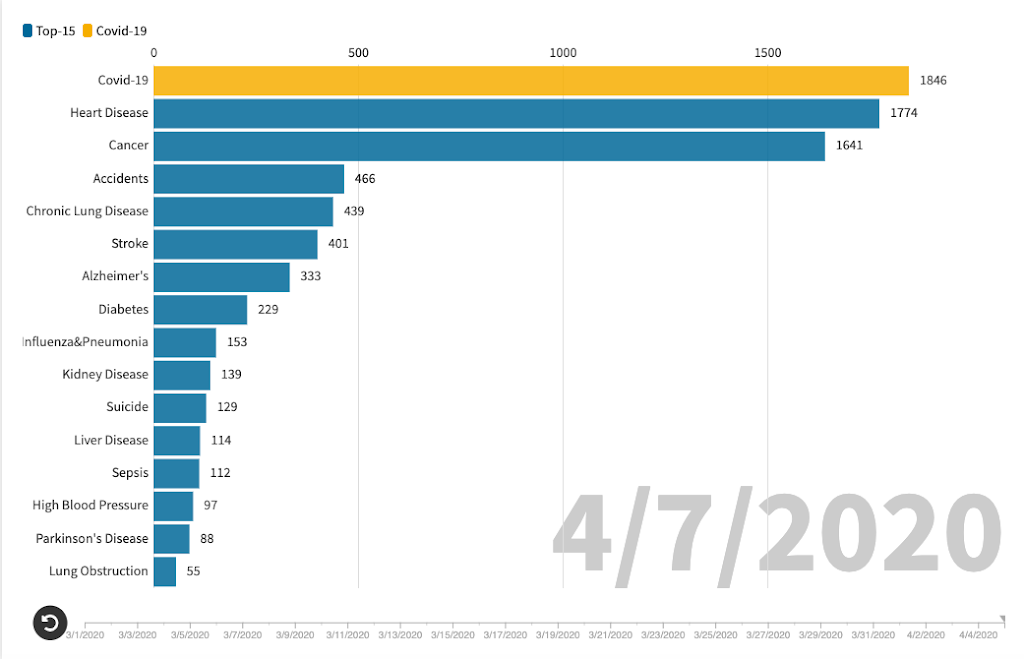

It is inevitable that not all citizens will share the same normative values or the same level of legitimacy in government. While most of us understand the need for extreme social distancing measures to save lives, some of us simply do not believe the facts the government cites as a basis for its decisions. We might think the government is ignorant, or we might think it is deliberately misleading us because of ulterior motives. We might think the government has good intentions, but is missing the mark with the policies. Or, we might simply find the new requirements unbearable.

Looking at my own reaction to the order, it was guided by similar questions. Is it true that there’s noncompliance? Yes, we have evidence of it in SoCal. Is it widespread? No, by the Governor’s own admission: “About 100 beaches, easily defined 100 beaches, and there were five where we had some particular challenges. Overwhelming majority there were no major issues. Quite frankly no issues,” he said. Is the reaction disproportionate to the threat? That’s a matter of perspective. Look at these concerns from local government officials:

California State Assemblymember Melissa Melendez fired back at Newsom’s decision on Twitter, stating “This is not going to end well. Californians are not children you can ground when they don’t ‘behave’ the way you want.”

Orange County Board of Supervisors member Donald Wagner on Wednesday acknowledged the governor’s ability to close the county’s beaches, but said “it is not wise to do so.”

“Medical professionals tell us the importance of fresh air and sunlight in fighting infectious diseases, including mental health benefits,” Wagner wrote.

“Moreover, Orange County citizens have been cooperative with California state and county restrictions thus far. I fear that this overreaction from the state will undermine that cooperative attitude and our collective efforts to fight the disease, based on the best available medical information.”

All the noncompliance factors are there: an emotional insult at not being respected enough to follow the rules out of our own volition, doubts about the values behind the approach (punitivism vs. fresh air), concerns that suppressing people too much will backfire and yield more noncompliance. Right out of the Coombs and Tyler playbooks.

The big question is: What, ultimately, will produce more compliance? Do we get more cooperation if we relax the order, counting on people’s common sense (and accepting that some will not display such common sense), or if we impose the order, counting on people’s agreement in principle? My gut tells me that, in the short term, enforcement stuff might be better, but in the long term, people’s sense of legitimacy and compliance will wear off, and we might see worse behaviors all across the state than the ones we saw on the beach. The problem is that levels of compliance are very tricky to model. They depend on demographics, political views, and other factors, which are changing daily, and would make this very difficult to predict even for compliance experts.

Ultimately, I think my personal reaction to this has been a great teacher. It opened some unexpected compassion gates: I managed to find within my soul more than a modicum of empathy for the feelings of Huntington Beach protesters, Spring Break revelers, and anti-vax conspiracy theorists. Don’t get me wrong: I have deep ideological disagreements with all these three groups and a much higher belief in the legitimacy of our local government (let’s talk about Trump some other day, shall we?). But what we share is the deep sense of emotional injury by a curtailment of a freedom we treasure. That’s something I can understand and sit with emotionally even as I ideologically disagree. In our case, my family treasures nature and water, and my son thrives during these difficult times because he has the world’s biggest sensory box to play and learn in. I very much hope our local government will not take this away from him.