Back when hadaraviram.com was California Correctional Crisis, I used to offer election endorsements for your consideration, focusing on the criminal justice propositions. This election has offered a grim opportunity to contemplate the probable victory of two seasoned and experienced politicians, whose management of the COVID-19 crisis in prisons has reflected an astounding moral eclipse.

A while ago, I posted an endorsement against Gov. Gavin Newsom’s recall. We were all experiencing collective distress over his reluctance to do anything useful to save lives behind bars from COVID. My reasoning was this: the rest of the ballot was a list of egomaniacal clowns with no political experience, many of whom could not even spell their statements. And, as I said there:

I’m not an idiot, and I do understand the concept of the lesser evil. If you are so warped in single-issue agitation that you can’t see the qualitative differences between Newsom–an experienced and capable politician–and the rest of the lot, you need better glasses.

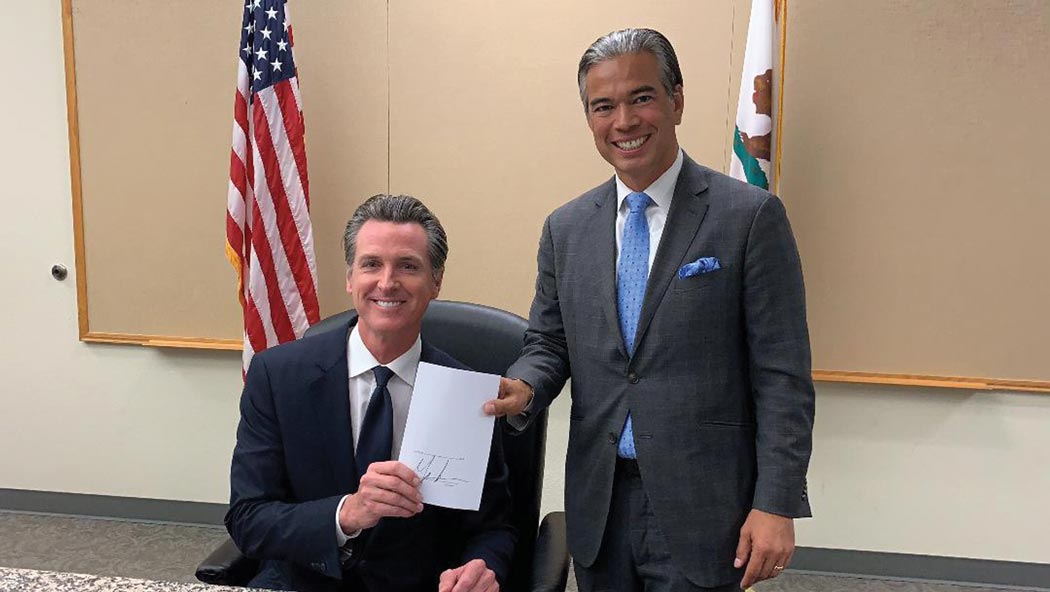

I wrote that post in August. in November, we found out that Newsom, the champion of science-forward, vaccine-forward policies in schools and everywhere else, thinks that unvaccinated guards are a-ok, and goes as far as to support them in their (devastatingly) successful appeal against a vaccine mandate. It was one of the ugliest examples of justice delayed becoming justice denied, can easily be attributed to the fact that the prison guards contributed $1.75 million to his anti-recall campaign, and has disillusioned me. I’ve come a long way from cheering for the then-Mayor of San Francisco who spoke at my 2005 PhD ceremony, and I’m feeling so full of bitterness and bile over the unnecessary loss of life that, this time around, I offer no endorsement for the gubernatorial position. Vote for whoever you want; Newsom will likely win.

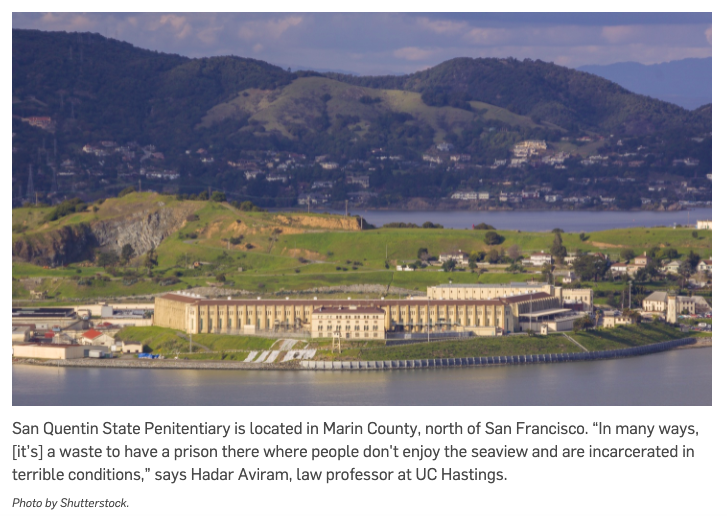

The other person to resent is Attorney General Rob Bonta, who is the darling of all the progressive voting guides. Bonta and his employees are the architects of the prison system’s defense against the COVID lawsuits, both regarding San Quentin and more generally in federal court. Their bad-faith in court appearances and representations, ugly games, and shocking lack of regard for human life has soured me on Bonta to the point that I make no endorsement, even though on paper he is the better candidate of the lot and will likely win. I explain my position in detail here. The short version is this: Bonta thinks that he works for us only when he legislates or creates policy, and that when his office litigates, he is the Tom Hagen of the prison guards. That’s an unacceptable perspective for a public servant.

I try not to be a one-issue voter, but having experienced the COVID-19 prison catastrophe up close it is very difficult to justify voting for Newsom and Bonta. Follow your conscience/calculus.

By contrast to these two, one public official shines as a person of profound understanding and conscientious behavior, and that is Phil Ting. I endorsed Phil’s assembly campaign in 2018 and am happy and proud to endorse him again; his conduct during the COVID-19 crisis was nothing short of exemplary. As Chair of the Assembly Budget Committee, Ting presided over a hearing in which, finally, Kathleen Allison was being asked hard questions about her policies and the way CDCR was handling itself. He has also been very sensitive to issues of parole and one of the only politicians with enough guts and public responsibility to realize that long-term aging prisoners are the best release prospects from both a medical and a public safety standpoint. Vote for him again.

There are two criminal justice issues on the ballot. One of them is the ridiculous Prop D, likely thrown into the ballot to add a prong to the Chesa Boudin recall effort by creating the (false!) impression that the D.A.’s office is not responsive to victims’ needs. There is a long tradition in CA of deceiving the voters to believe that there is a need for a victims’ bill of rights and services, when one has existed since 1982 (I explain all this in Chapter 3 of Yesterday’s Monsters.) Just like Marsy’s Law and other deceptive initiative tricks, this is money allocated to no good cause, creating duplicative services that already exist. The Chron is far too gentle on this. Don’t be swindled – vote NO on D.

Finally, speaking of swindling, you already know my position on the Boudin recall effort. There’s a well-oiled, well-funded machine here trying to roll back important reforms, and exploiting people’s exasperation at the misery and turmoil in town, which are NOT Boudin’s fault by a longshot. Don’t be deceived! Vote NO on H.