Unbelievable and unconscionable. NBC News report:

A federal appeals court on Friday temporarily blocked an order that all California prison workers must be vaccinated against the coronavirus or have a religious or medical exemption.

A panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals granted a request for a stay of September’s lower court order pending an appeal. It also sped up the hearing process by setting a Dec. 13 deadline for opening briefs.

The vaccination mandate was supposed to have taken effect by Jan. 12 but the appellate court stay blocks enforcement until sometime in March, when the appeal hearing will be scheduled.

A horrifying and preventable catastrophe

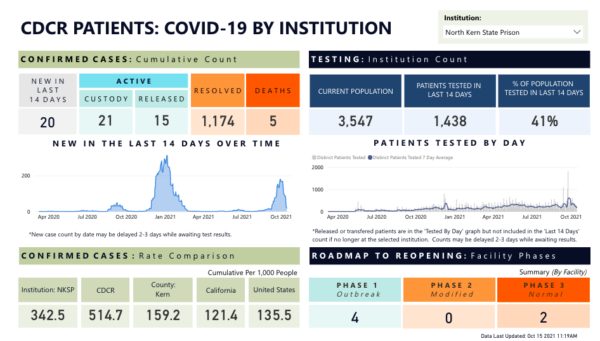

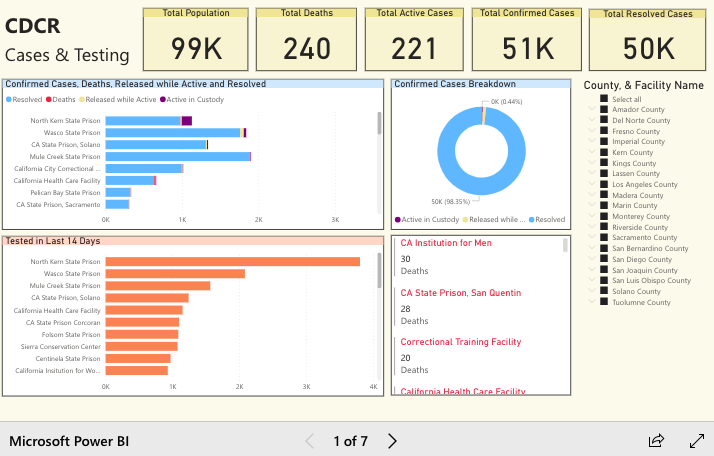

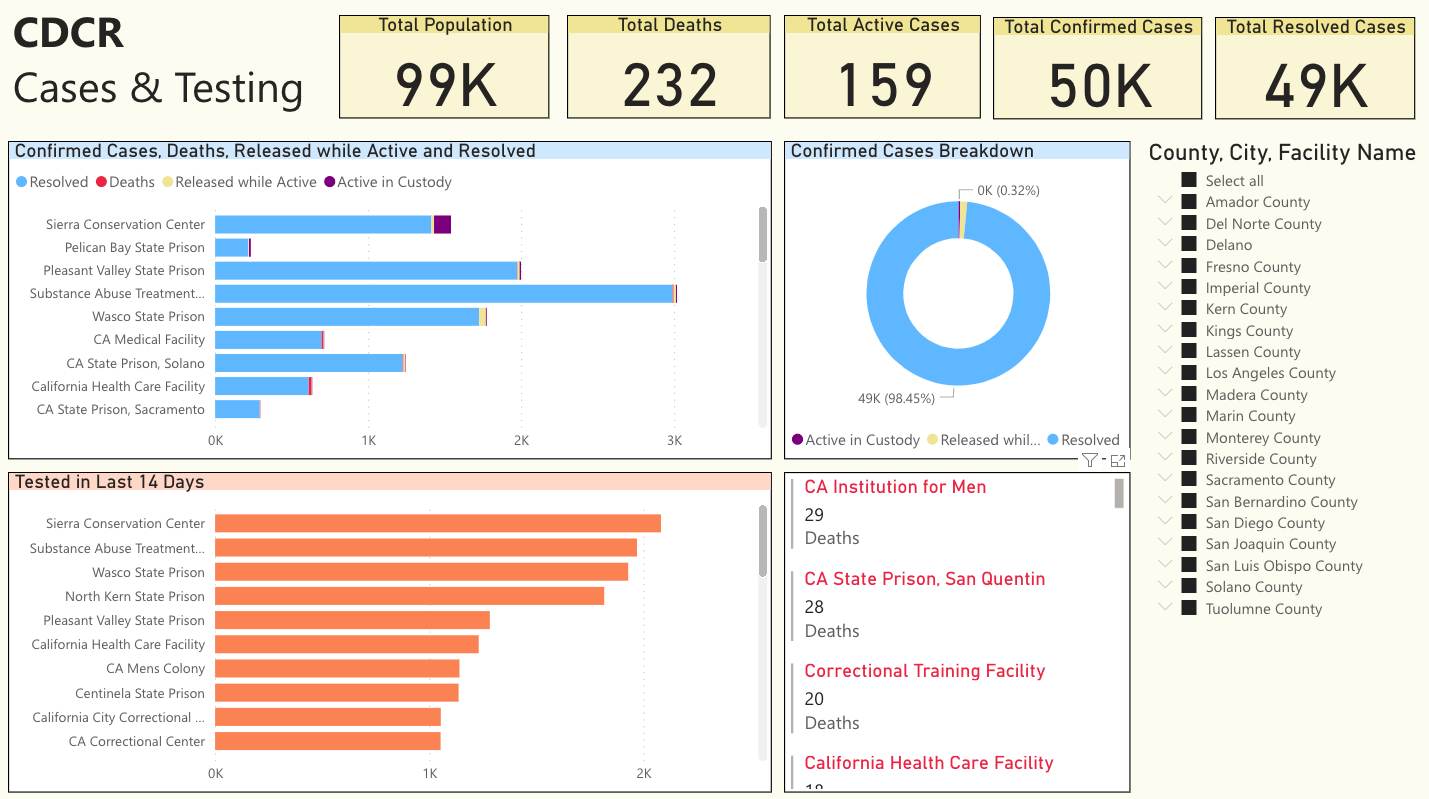

It is absurd to deny that a horrifying and preventable catastrophe has played out in California prisons. So far, more than 50,000 people—more than half the state’s prison population – has contracted COVID-19, and 242 people have died. The California Inspector General’s reports, as well as federal and state court findings, reveal a picture of shocking indifference, shortsightedness, and neglect in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR) handling of the pandemic—complete with irresponsible transfers, an overwhelm of the prison healthcare system, low testing rates, a rumor mill of fearmongering and disinformation, and unreliable data collection.

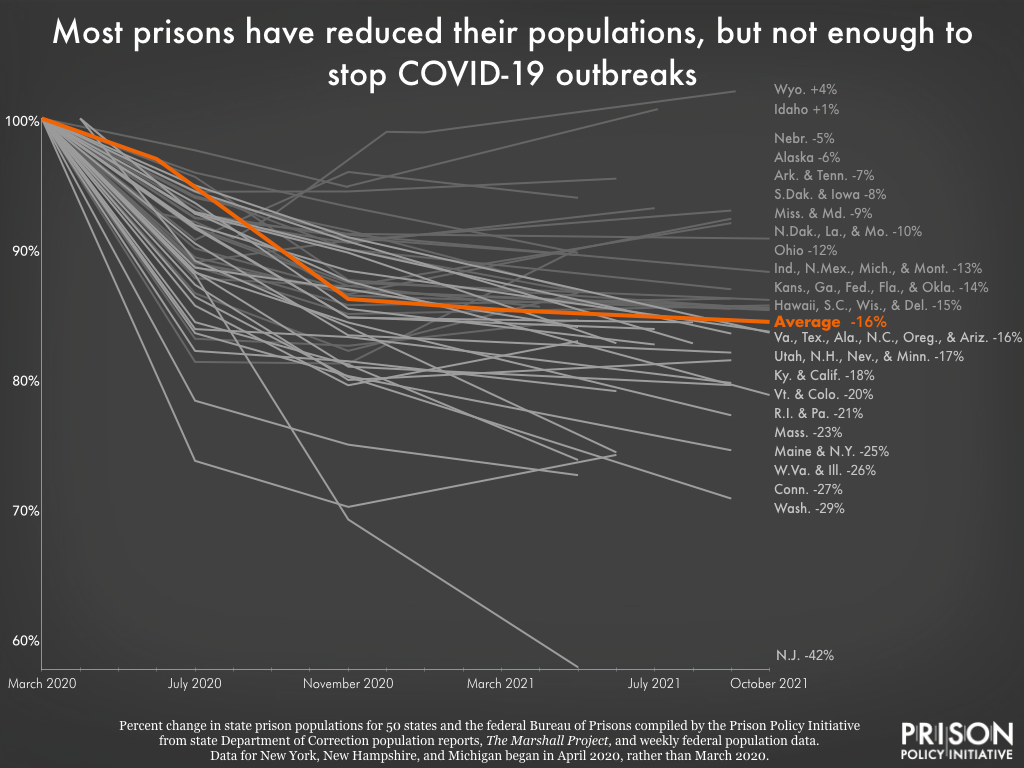

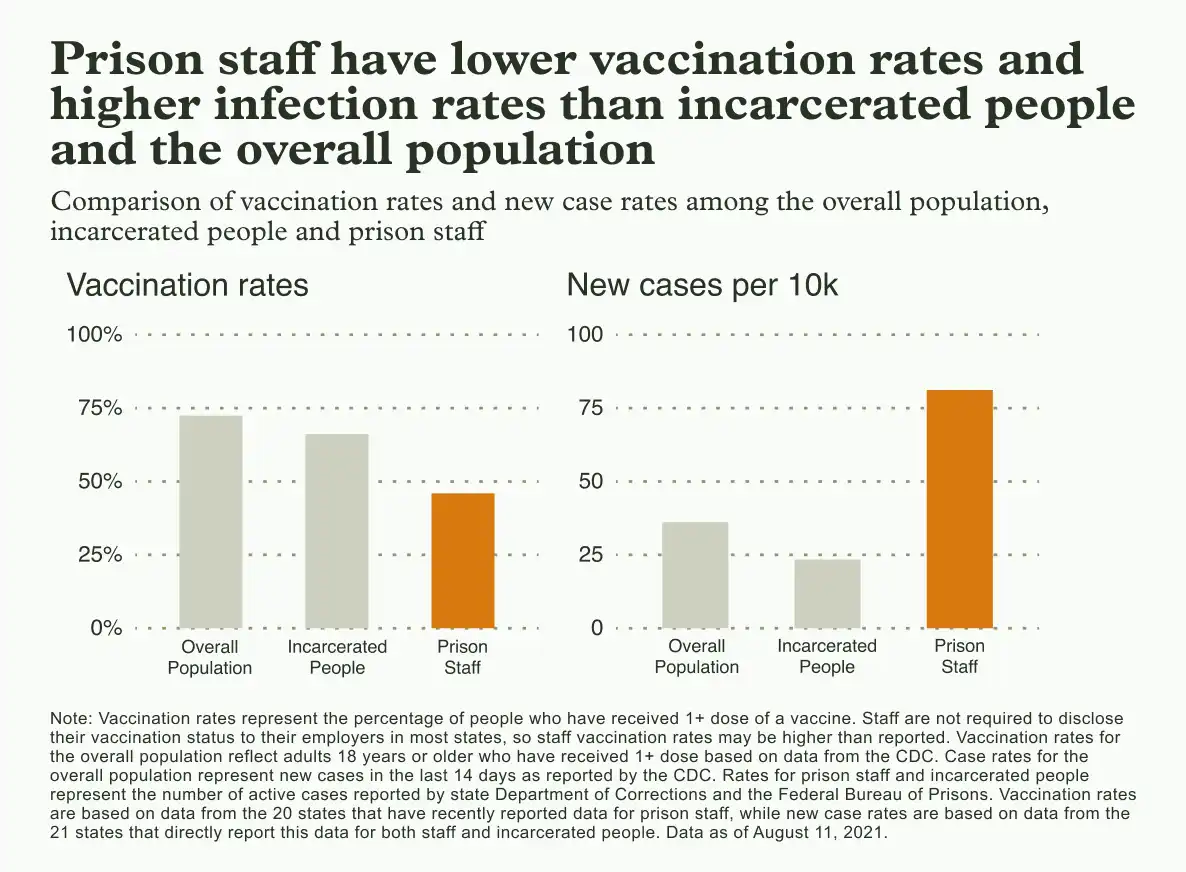

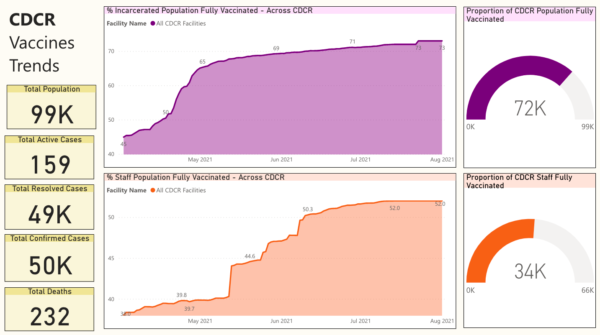

For a year and a half, advocates for incarcerated people fought in federal court to obtain relief. The lawsuit began as a plea to reduce prison population, which for much of the pandemic hovered around 100% of design capacity. But with the advent of vaccination, and after an uphill battle to ensure that prisoners, like other people living in congregate settings, receive it, the lawsuit’s focus became much more modest: a mandate that correctional staff (the main transmitters of the pathogen) become vaccinated. Despite concerns that prisoners, who have lost all faith in CDCR, would be suspicious of the vaccine, advocacy groups comprised of physicians, family members, and recently released people, succeeded in providing accurate and trustworthy medical information, resulting in high vaccine acceptance rates among the prison population.

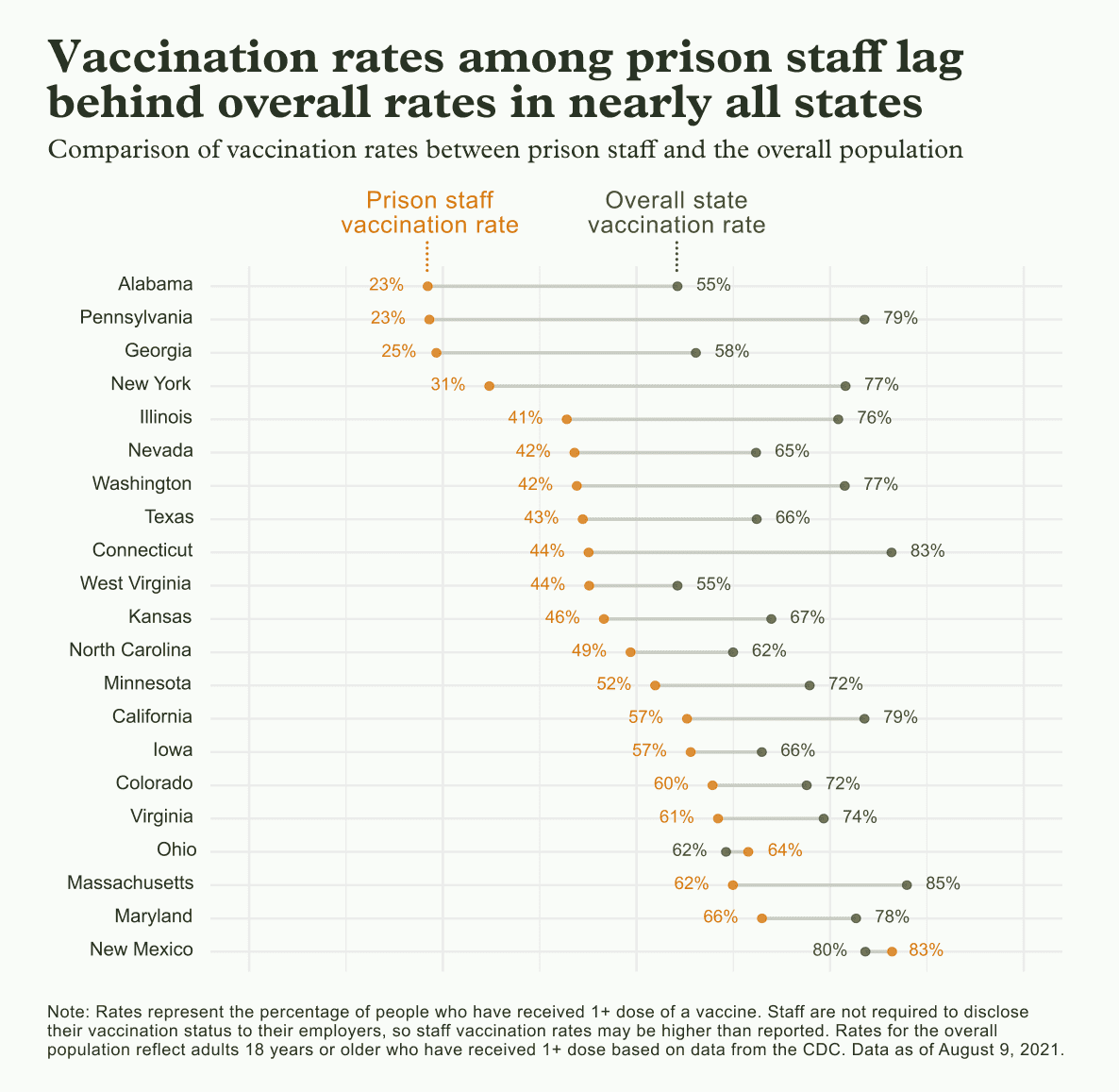

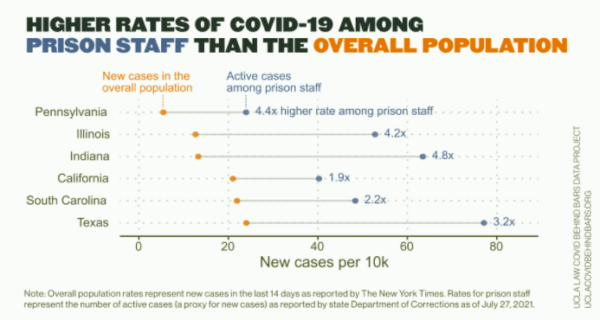

The picture is completely different regarding prison staff. Throughout the pandemic, correctional officers told incarcerated people that COVID-19 is a hoax and that the vaccine would kill them; neglected to wear PPE in enclosed spaces and mocked prisoners for doing so; ordered prisoners to clean cells of infected people; fed prisoners insufficient, unpalatable food when the pandemic ravaged kitchen workers; and planned a correctional officers’ union event in Las Vegas amidst the pandemic wave of late 2020, which was abandoned only under public pressure. Even as their colleagues ailed and died, many correctional officers persisted in COVID-19 denialism and anti-vaccine sentiments.

The stay is the last in a long series of concessions and placations by government officials to the powerful prison guards’ union. Throughout the litigation, Judge Tigar exhibited remarkable patience and tolerance for bad faith arguments, trying to foster cooperation rather than impose orders and congratulating attorneys for the prison guards’ union for even sitting at the (virtual) table. Then, Governor Newsom—ostensibly, the outspoken architect of California’s science-forward vaccination policy and of vaccine mandates in schools—supported the guards in their bid to evade vaccination (the prison guards’ union reportedly contributed $1.75 million to Newsom’s anti-recall campaign). Attorney General Rob Bonta, who publicly decried the pandemic crisis at San Quentin as an Assemblymember, changed his tune as soon as he took office, and has allowed his employees to defend the prison system’s unconscionable policies.

This disturbing pattern offers somber proof that all government branches are paralyzed not only by fear of unflattering optics—the people who should be first in line to be released, elderly and infirm prisoners, are often serving time for serious, violent offenses—but also by the manipulations of the prison authorities and the prison guards’ union. In one case, justice delayed due to these evasive maneuvers was, literally, justice denied: Just a few weeks ago, Judge Howard of the Marin Superior Court found that the ill-fated transfer that started the horrific San Quentin outbreak constituted an Eighth Amendment violation—but offered the prisoners no relief, because the vaccines supposedly “changed the game” to a point that lifesaving population reductions are moot.

The Remaining Threat

But the threat is not moot; currently, there are several active outbreaks in California prisons and dozens of active cases. Studies are increasingly showing that the congregate setting in prisons, complete with flawed ventilation, lack of social distancing, and the rise in prison population, pose continuous risks. Efforts to control prison populations by stopping jail transfers are currently causing massive outbreaks in several county jails. Moreover, the emergence of new variants, such as Omicron, does not bode well for correctional facilities.

The risk extends far beyond the prison gate. For our forthcoming book about the California COVID-19 prison crisis, my coauthor Chad Goerzen and I have found worrisome correlations between prison outbreaks and spikes in cases in surrounding and neighboring counties. We should all know by now that the pandemic is not a zero-sum game. Viruses do not decide which hosts to inhabit based on arguments of moral deservedness or the California Penal Code. If prisons are allowed to incubate dangerous variants, the risk to you and your loved ones increases.

The Ninth Circuit reasons that anti-vaccination sentiments run rampant among prison guards (we do not know why, as no one has ever systematically surveyed the political views of correctional officers) and assumes (without foundation) that, in the face of vaccine mandates, many might quit their well-paying jobs, leaving our vast prison system understaffed. This scenario was feared, but failed to acknowledge that in many other employment sectors with mandates, where vocal protestations and threats of resignation gave way to vaccine compliance. ‘

But even if the threat of correctional officers’ resignations is real, we must ask ourselves why courts and government officials are so stubbornly clinging to the idea of overcrowded prisons as a social good. If it is impossible to hire and retain correctional staff who can provide a standard of care that complies with minimal Eighth Amendment requirements, then it is impossible to incarcerate as many people as we do. We must reckon with the fact that we cannot, lawfully and constitutionally, house more than 100,000 people—a quarter of whom are over 50 years old—if the staff entrusted with their care cannot be bothered to take minimal precautions to protect their captive wards from disease.