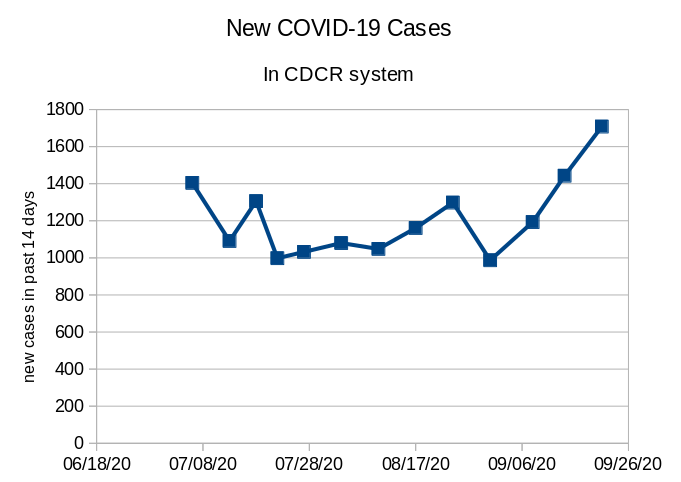

Now that we’ve had a couple of hours to digest the good news about the population reduction order from In re Von Staich, it’s time to start thinking about next steps. What happens now at San Quentin, in other prisons and jails, and in the courts? Here are some of my initial thoughts on the topic–feel free to share yours.

How can CDCR and Quentin comply with the order? The order is not dissimilar from the Brown v. Plata order: it requires a population reduction, but doesn’t bind the prison to a particular way of achieving it. They could do any number of things. The best case scenario is one in which they heed the Court of Appeal’s strong recommendation to expedite the release of everyone who is over 60 and has done 25 years or more, but I’m not holding my breath. They could also transfer people into other prisons, keeping the aging old-timers inside, in which case they’ll still be in compliance with Von Staich – they’ll be giving the folks inside more room for social distancing. How they can accomplish this without touching the very people they needed to release first but won’t (folks who are sick and have aged out of crime) is largely a numbers game. These folks are about 30% of the prison population, and without even touching this category, it’s dubious that they’ll be in compliance with the order.

Is CDCR going to appeal? What will they argue? Of course they’re going to appeal. Is there any doubt? This process has been saturated in bad faith and obstinacy, and that animus is likely to continue. On appeal, they will likely argue that the decision not to hold evidentiary hearings (as they are holding in the Marin cases and in Plata) was hasty and unfounded, and that their mishandling of the crisis does not rise to “deliberate indifference.” It’s going to be pretty difficult for them to argue that the remedy is excessively burdensome given how much latitude they were given. They only have 15 days to pull together an appeal, so we’ll find out pretty soon. Whether or not CDCR will get a stay from the Supreme Court is another interesting question. If they don’t, they’ll have to work simultaneously on their appeal and on their population reduction strategy. This scenario closely resembles what happened in the late 2000s, when Plata was making its way from the federal panel to the Supreme Court: The Attorney General (then Jerry Brown) fought tooth and nail against the order, while at the same time considering the legislative “fix” that became the Public Safety Realignment (AB 109.)

What does this mean for jail transfers into San Quentin? The opinion itself says that, so far, much of the population reduction that CDCR boasts was achieved via a temporary halt of transfers. This has had the unfortunate effect of exacerbating COVID-19 in overcrowded jails; the horrific outbreaks, isolations, quarantining, and misleading information about Santa Rita is a case in point. This is not a good long-term solution, obviously, but whether or not they will use this as their population reduction mechanism depends on how pressured they are to find a more general solution to COVID in the entire system.

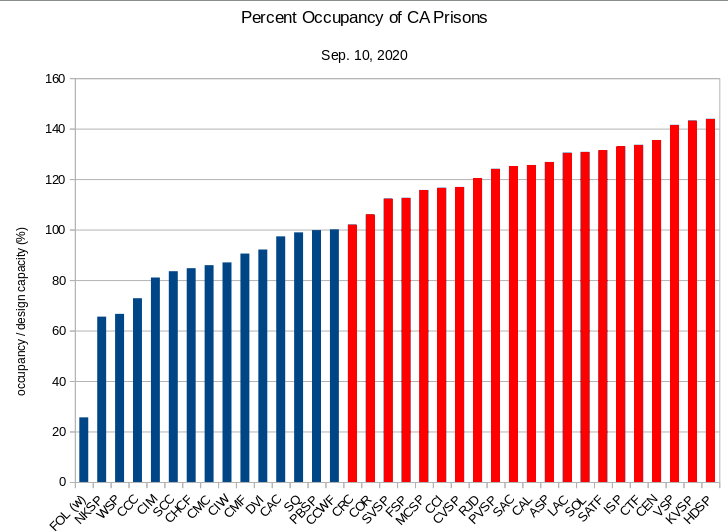

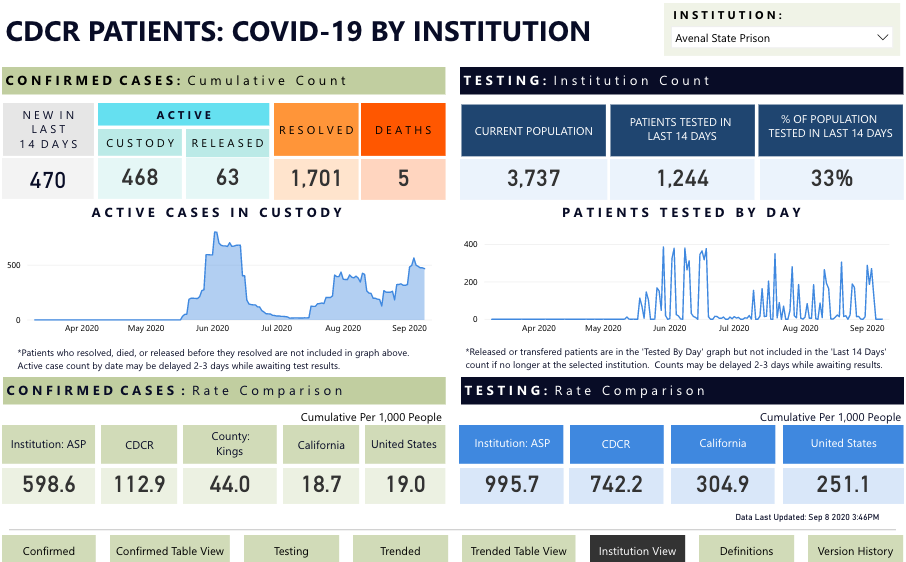

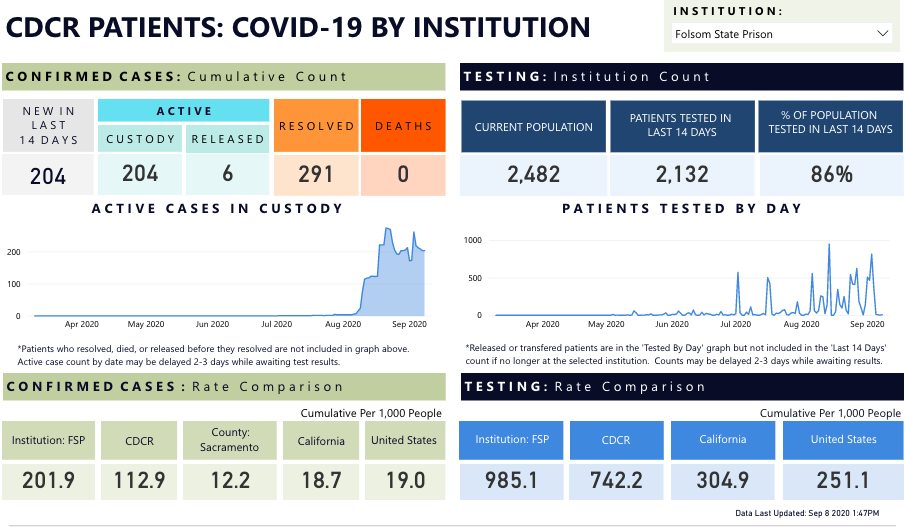

What does this mean for other prisons? I have similar thoughts on this. The decision explicitly says that, if CDCR officials feel that they can’t appropriately guarantee public safety via releases (they can, but okay) they can resort to transfers. The problem–which the decision also flags–is that this whole catastrophe started with a transfer in the first place. Can CDCR be trusted to transfer people out to prisons with no or low COVID numbers in a safe manner–that is, by testing and isolating them? And can they be trusted to cooperate with health officials in the surrounding/bordering counties to guarantee that there’s no corresponding spike in the new country? Their record has been abysmal, but that’s not to say they won’t try.

How is this going to impact Plata v. Newsom? The short answer: it’s not. The litigation in Plata addresses the entire system and is all-encompassing. The long answer is that it’s complicated. The factual findings in Plata might change based on whatever transpires in the aftermath of Von Staich. If CDCR chooses to respond to Von Staich with transfers, and these cause further outbreaks, the scope of litigation in Plata, and the remedy, will change accordingly.

How is this going to impact the Marin Consolidated Cases? This is a far more interesting question, because the Marin cases are scheduled for an evidentiary hearing on October 26. One of the fierce battles in Von Staich was over the need for an evidentiary hearing: the AG representative implored the court to “not act hastily” and to find out facts; Justice Kline replied, “yes we do, yes we do, we do need to act hastily.” In the opinion, he wrote that CDCR denied all the allegations made by petitioners, but made no effort to counter them with evidence of their own. One possibility, based on this opinion, is that the attorneys for the Marin petitioners will argue that Von Staich, decided by a higher court, now governs the case, and that instead there needs to be a focus on how CDCR implements the remedy. If the AG representatives argue that they want the hearing nonetheless, that puts them in conflict with Von Staich, even though there’s no formal estoppel (different petitioners.) It’s going to be interesting, for sure.

What should we do next? Well, we need to sit tight and watch what CDCR/the AG’s office does. In the meantime, it is imperative to do the following:

- Reach out to CDCR with concrete, sane, practical proposals for a 50% population reduction, such as the ones that Jason Fagone lists in this Chron article.

- Put enormous pressure on Gov. Newsom to modify his inadequate release plan in line with Justice Kline’s recommendations.

- Embark on a huge education campaign about the catastrophic risks of transfers, such as the ones that brought about the calamity at Quentin in the first place.