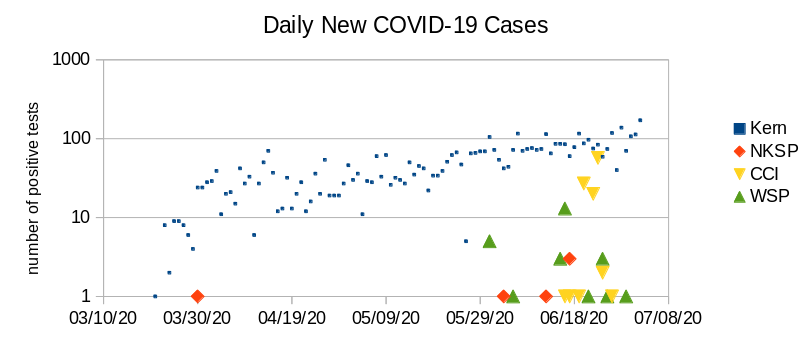

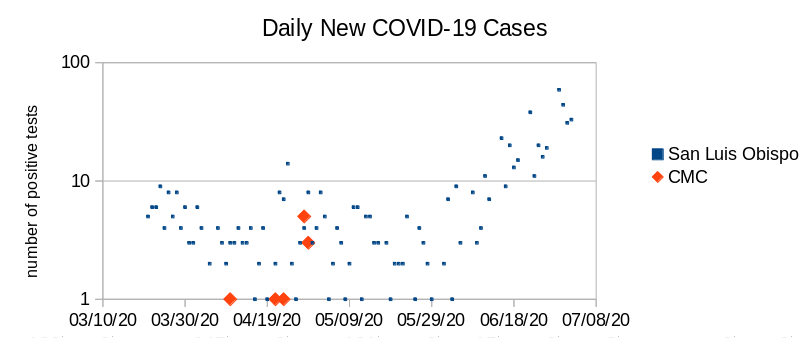

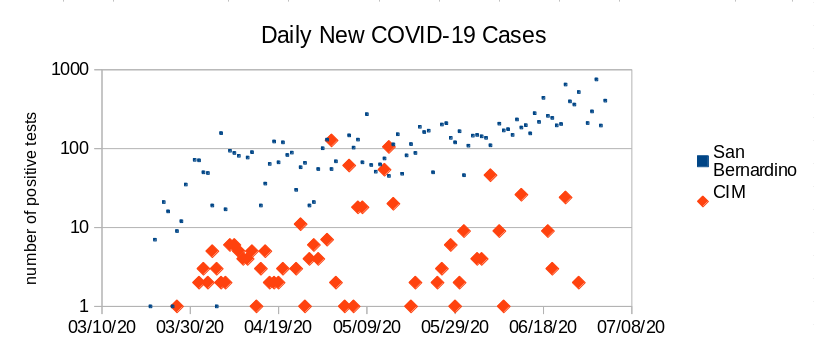

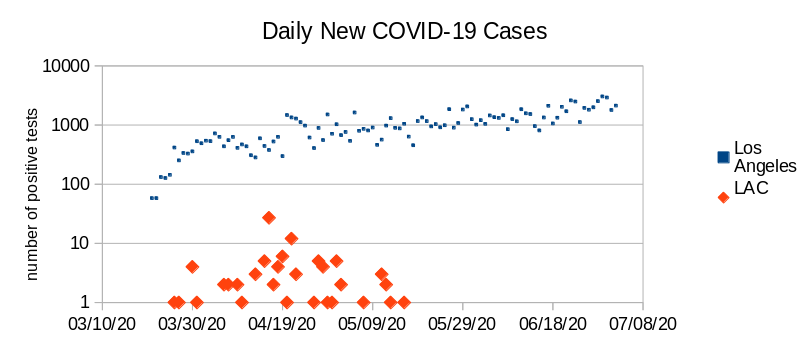

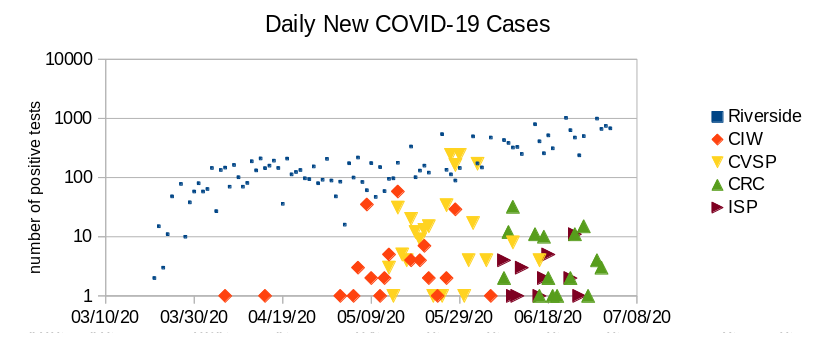

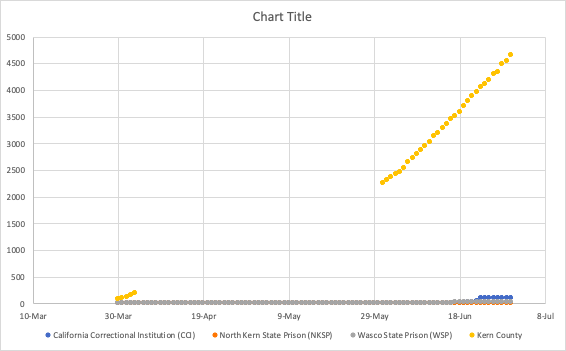

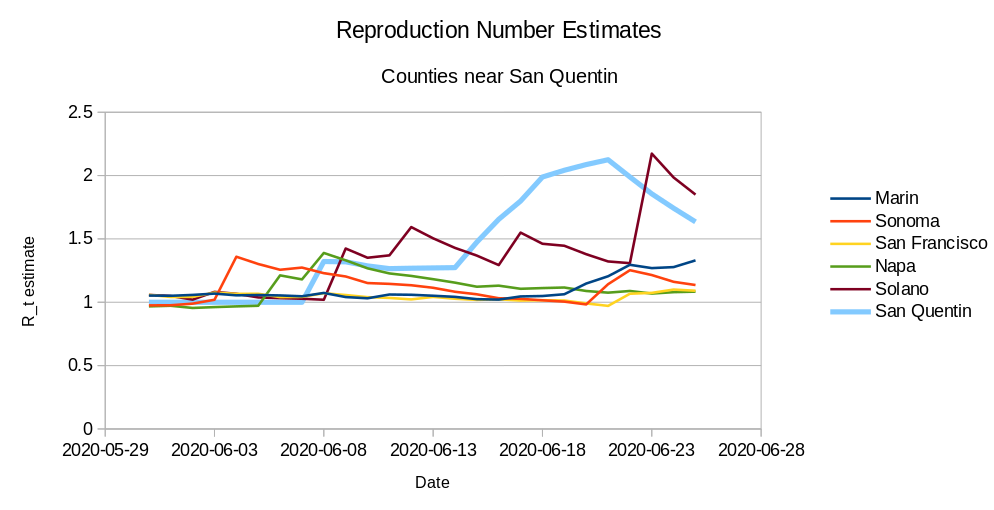

I thought prisons were safe. How did the virus even get into prison? Because prisons in California are often in remote, rural areas, it’s easy to think of them as impermeable and far away, but that is not the case. In all prisons, staff members go in and out of the facility, and often live in the surrounding counties. This is how infections can permeate the prison from the community. But CDCR has also made some horrific decisions to transfer people between institutions without proper testing and quarantine protocols. These transfers are probably the source of the serious infection at San Quentin and the spread at Corcoran, as well as in Lassen County and other places. Recently, the medical officer of CDCR was ousted because of these instances of mismanagement.

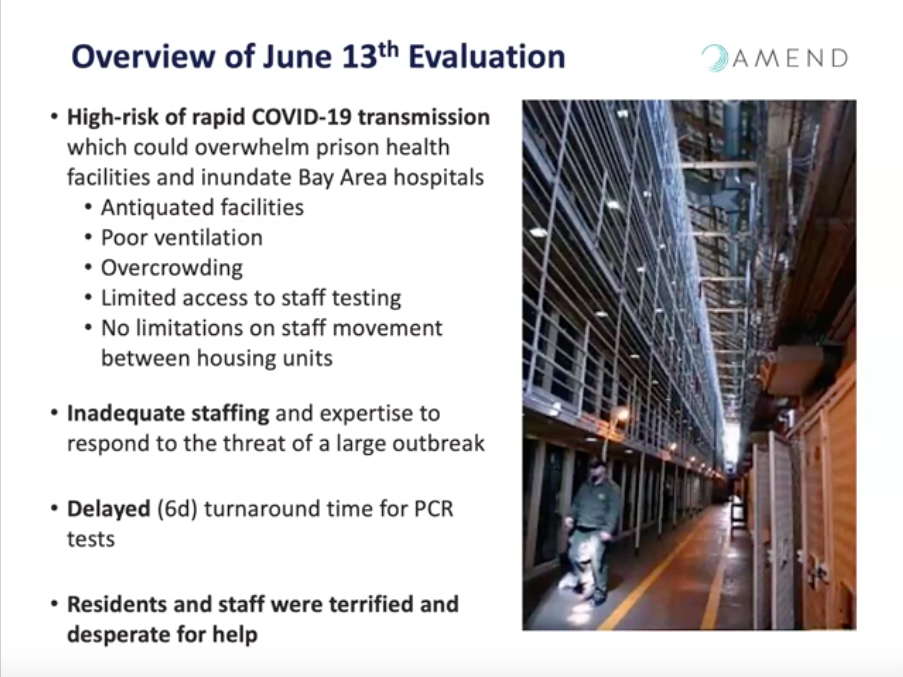

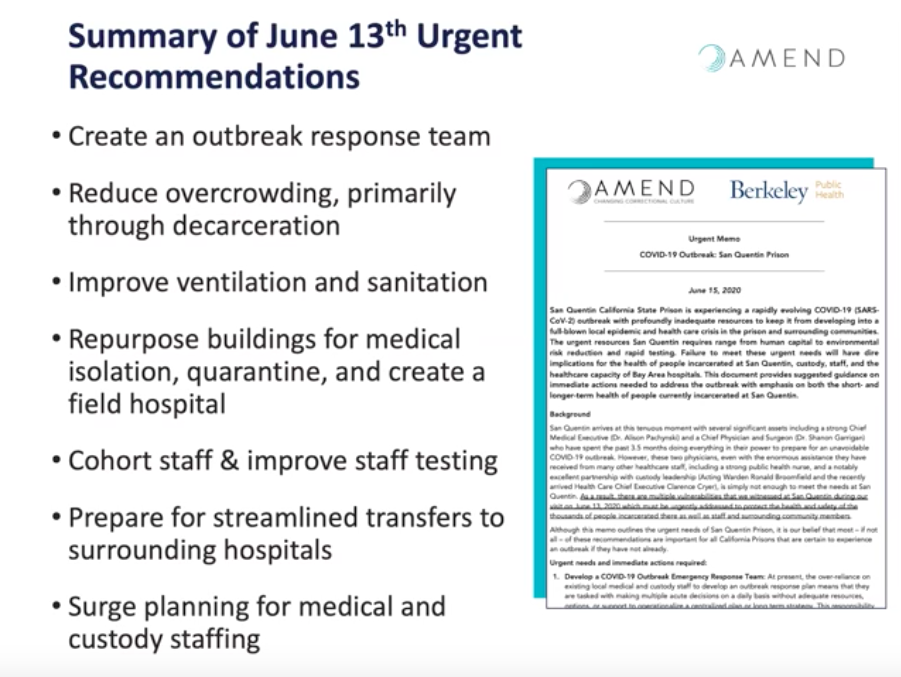

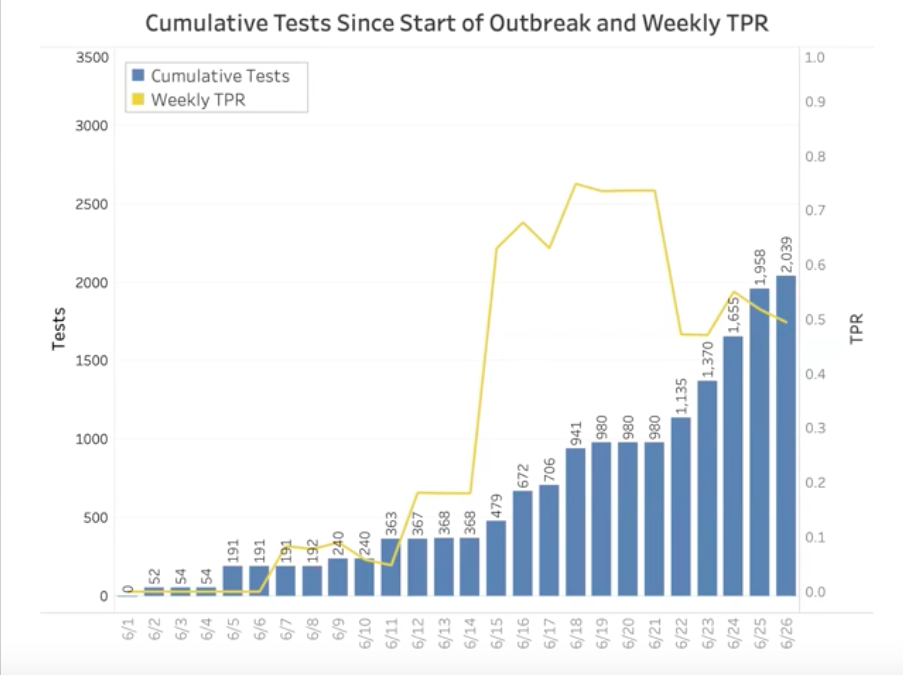

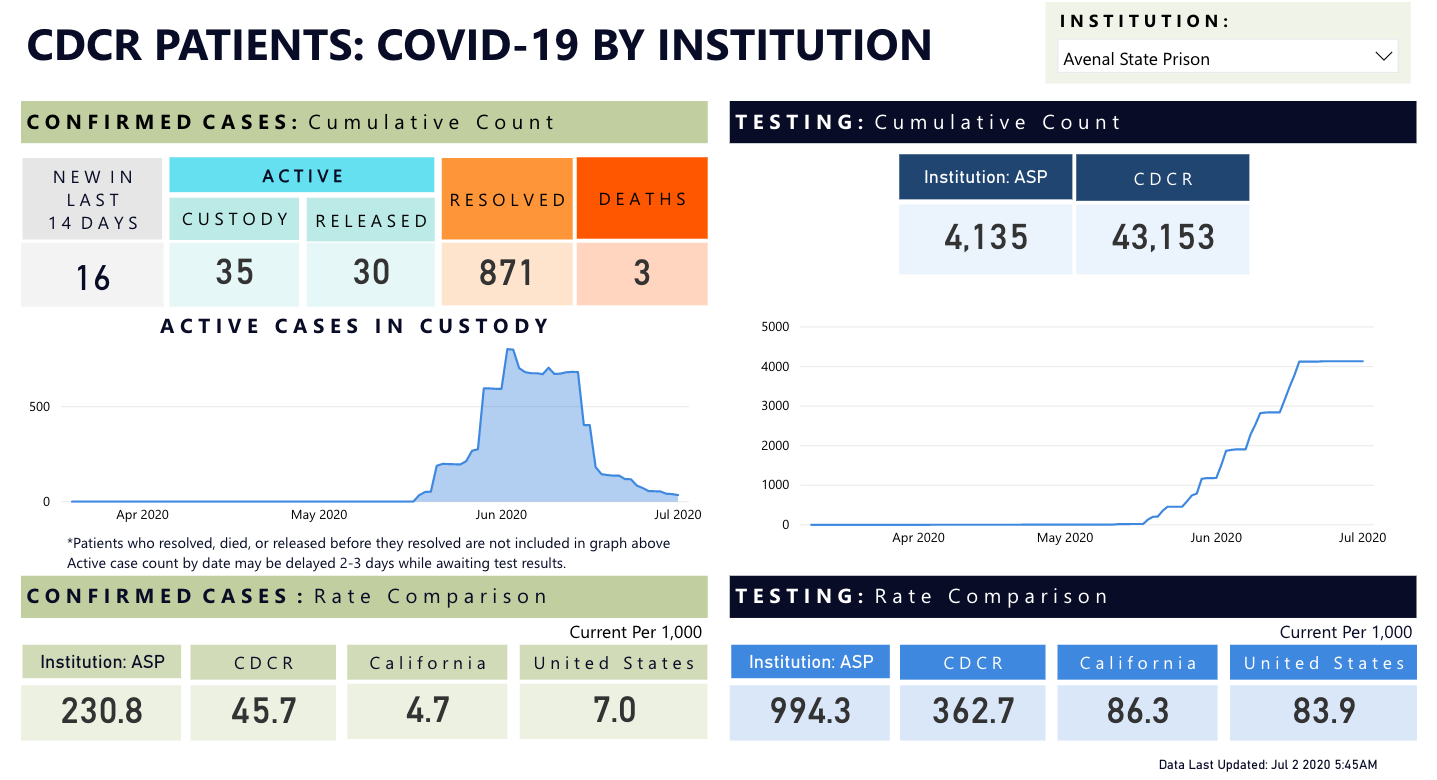

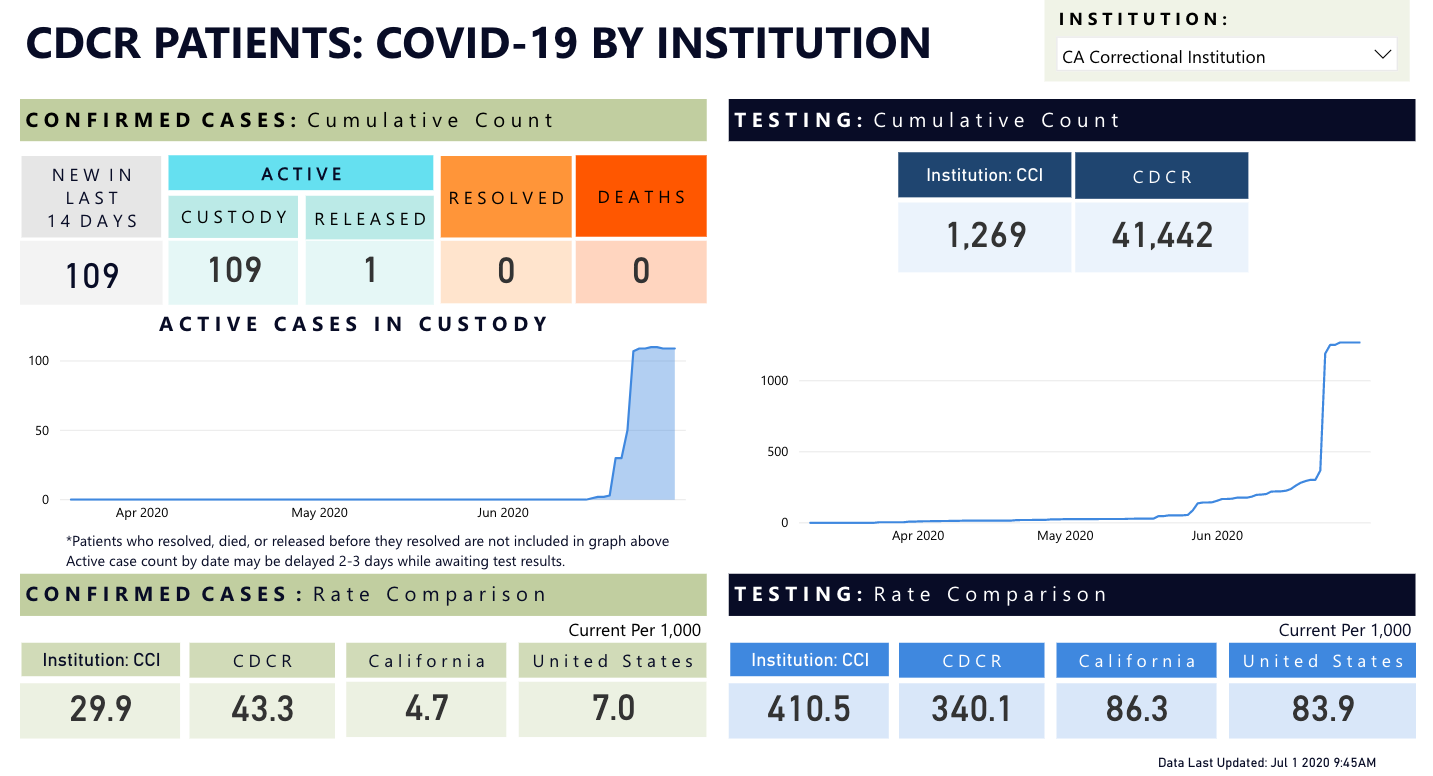

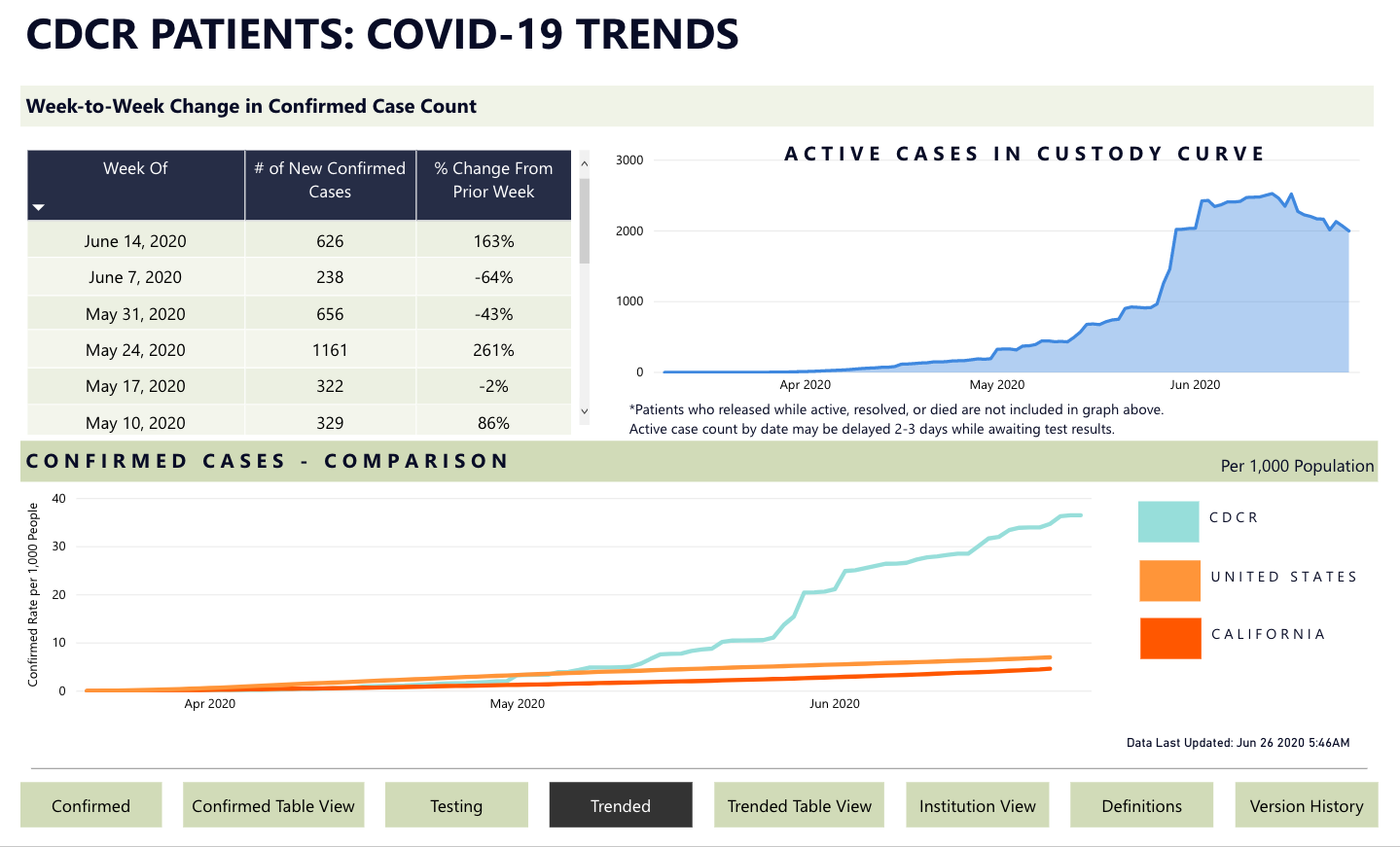

Why is the virus spreading in prison? Almost all the prisons in California are overcrowded, some of them to the tune of 150% of their design capacity. Social distancing is difficult to do under these conditions. Some well-intentioned, but shortsighted, strategies we took to resolve this problem has just made prisons and jails more vulnerable to the virus. Staff circulate around the prison, as do workers who are incarcerated themselves; there are no solid protocols on cohorting these populations to prevent the spread.

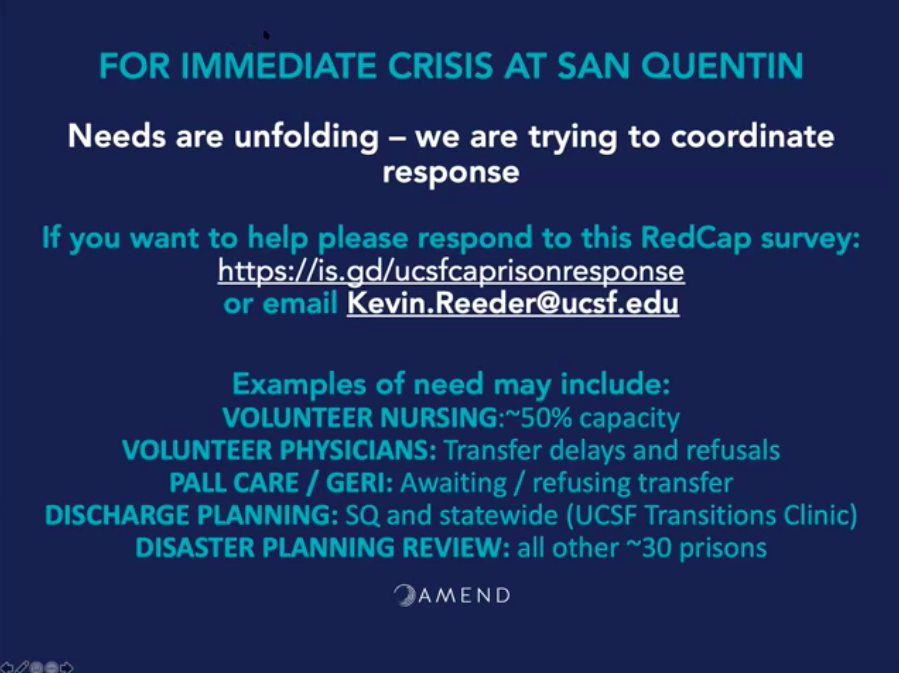

Aren’t the sick people receiving free healthcare in prison? What people in prison receive is not “healthcare” as you understand it. It is appalling and neglectful, and often features weeks (sometimes months and years) of delays. Not too long ago, a person would die behind bars every six days from a preventable, and sometimes iatrogenic, disease. And, until recently, people paid copays for the “healthcare” they receive. The medical system was overwhelmed before the pandemic, despite desperate efforts to turn things around; overcrowding was, and still is (albeit to a lesser degree) still a complicating factor.

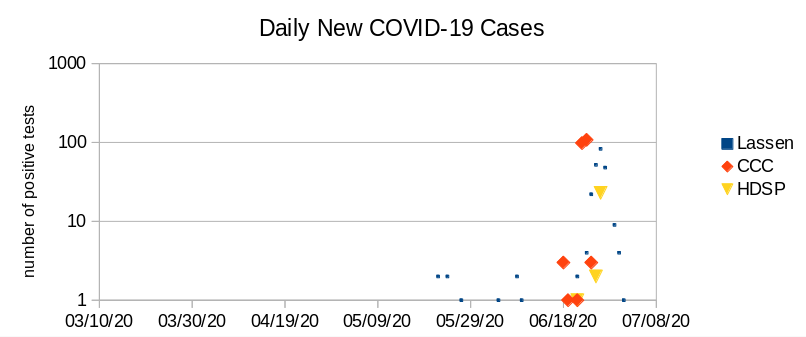

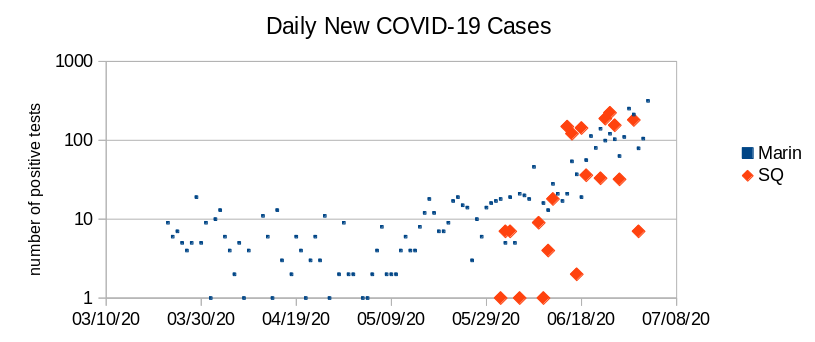

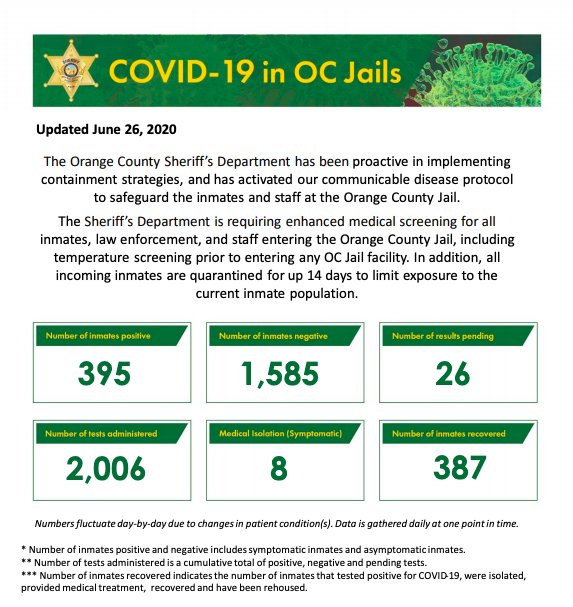

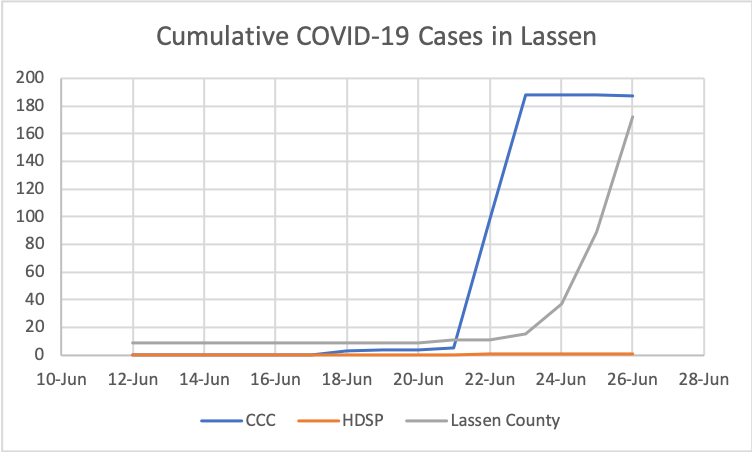

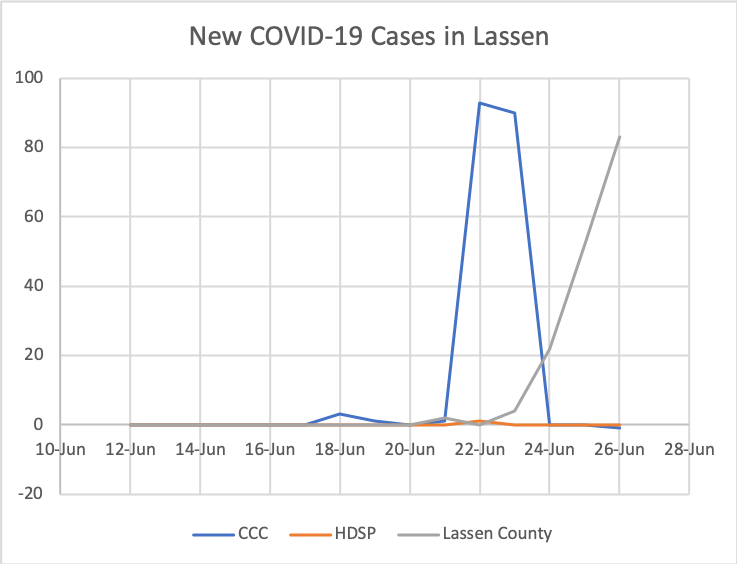

Aren’t the sick prisoners safer in prison, where they can be isolated from the rest of the community? No. By and large, prisons are doing a very poor job putting together social distancing protocols. COVID-19 is ravaging death row, where people are single-celled and you’d think would be protected from each other. And we are not safer if the virus is incubated in prisons, either. In at least two counties, Marin and Lassen, infections in the community spiked shortly after infections in prison spiked. Prisons are part of the community, and people in prison are members of the community. Staff go in and out of prison every day, sometimes multiple times a day. They live where you live; they eat where you eat; they shop where you shop. Keeping people in prison, where prevention and treatment are impossible, incubates the virus in prison, creating, essentially, a reservoir of illness to ravage the surrounding community.

Can’t we use solitary confinement to isolate sick people? No. Medical isolation and solitary confinement are two completely different things, as Cloud et al. explain in this article. Threatening people with solitary or death row celling terrifies them and disincentivizes people from reporting their symptoms and from getting tested. It is counterproductive and cruel.

But didn’t we already decide to release some people? So far, Gov. Newsom has only released 3,500 people, and is planning on 3,500 more. It is a mere drop in the bucket. We need to release tens of thousands of people to see improvement in the contagion. Remember that, following the 2011 Realignment, we released 40,000 people, are still wrestling with quality of healthcare, and that was without a pandemic going on.

Didn’t the Governor say that the prisoners don’t have anywhere to go? The Governor’s approach to this–to examine cases one by one for “worthiness” or “eligibility”–might have been a good fit three months ago. Now, we need to triage because we are facing a disaster on an enormous scale. Many people do have loving family members and friends who are happy to welcome them back to the community. Volunteers and advocates are at the ready to help with housing solutions.

If we release people, shouldn’t we prioritize nonviolent drug offenders over violent criminals? The distinction between so-called “nonviolent” and “violent” offenders doesn’t mean anything in terms of the risk they pose to the community. A quarter of the California prison population are people aged 50 and older. These people do not pose a risk to public safety, regardless of the crime they committed decades ago. At this point, “prioritizing” is no longer a luxury we have. We must let people out in large numbers to contain the virus and prevent the prison from turning into a mass grave.

If we release criminals into the streets, won’t that endanger public safety? No. We did large-scale releases before, in 2011 and in 2014, and crime rates, particularly violent crimes, did not go up. If we see an uptick in crime in the following months, it will likely be the natural outcome of the relaxed pandemic prevention restrictions, and will not reflect people released from prison. When you see newspaper articles

Aren’t people on death row going to die anyway? No. California has a moratorium on the death penalty. And before the moratorium (and even now, because the death penalty is still in the book), we have litigated for decades, to the tune of billions of dollars, how to appropriately and constitutionally execute people. We were even careful, absurdity of absurdities, to examine whether people were healthy enough to be killed by the state. We have not made this effort and spent this money so that people could die via COVID-19. Also, keep in mind that a proportion of these people are innocent of the crimes they were sentenced to death for.

We have limited resources, and I’d rather spend them on deserving people than on people who committed violent crime. It is true that we have limited resources, and because of that, they must be spent where they can help us prevent contagion, illness, and death. COVID-19 is not a zero-sum game; it’s not like there’s an allotted number of sicknesses and you get to decide who deserves or does not deserve to get sick. Prisons are not separate from the community; they are part of the community. Allowing the contagion to ravage prisons incubates the disease within the prisons and poses a risk to all of us. If people in prison get sick, people outside of prison get sick, including you and your loved ones. It is an urgent priority to spend the resources where they can prevent illness and death for all of us.

I don’t care about people in prison. You do the crime, you do the time. The people serving prison sentences in California were sentenced under the California Penal Code. The Penal Code does not sentence people to neglect, abuse, contagion, illness, and death. Moreover, many of the people serving time in prison, and even on death row, are factually innocent. But more profoundly, ask yourself what role your lack of compassion for fellow human beings is playing in your life. A Cherokee story tells of a wise grandfather and his grandson. The grandfather says, “Son, within each of us there is a battle between two wolves. One is evil. It is anger, envy, jealousy, sorrow, regret, greed, arrogance, self-pity, guilt, resentment, inferiority, lies, false pride, superiority, and ego. The other is good. It is joy, peace, love, hope, serenity, humility, kindness, benevolence, empathy, generosity, truth, compassion, and faith.” The grandson asks, “Which wolf wins?” The wise grandfather replies, “the one you feed.”