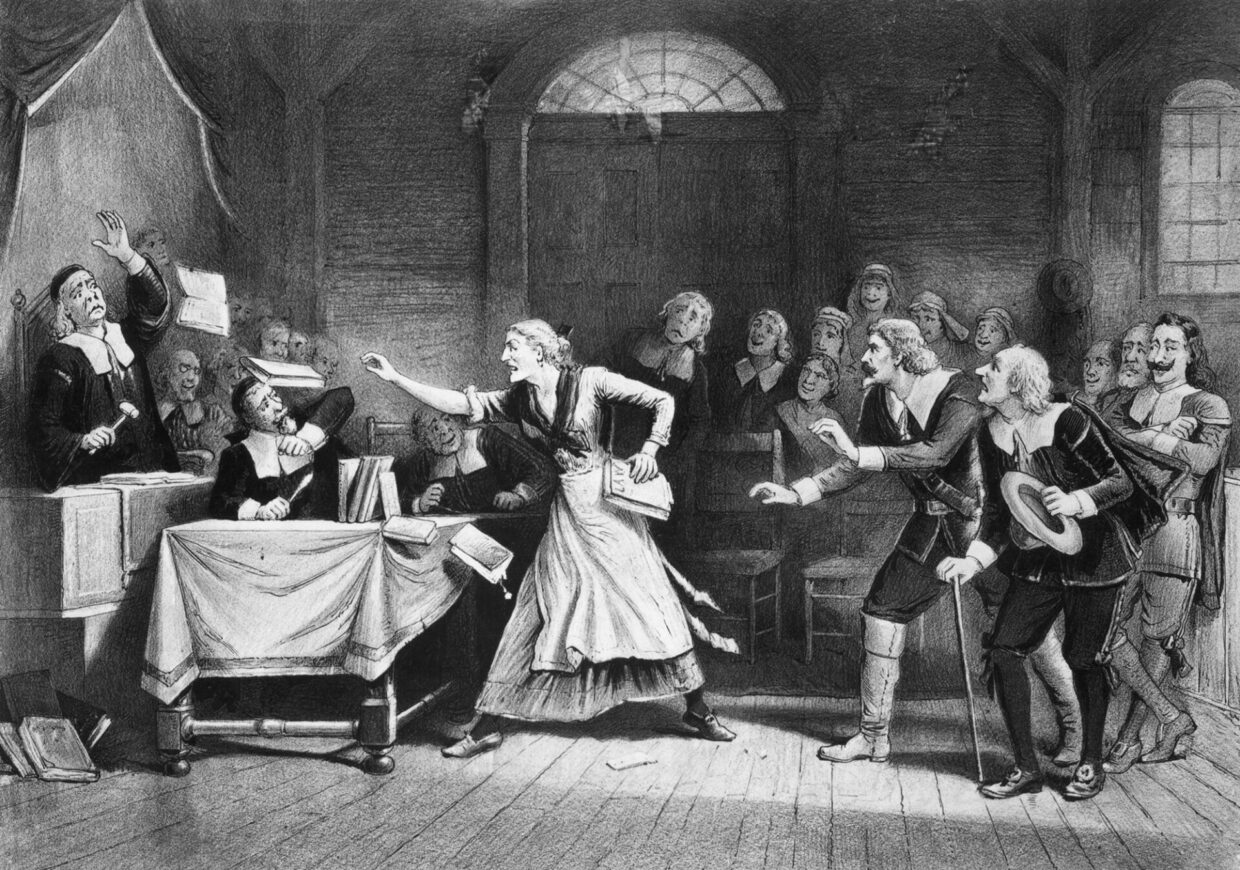

Many years after writing his play The Crucible, Arthur Miller reflected in the New Yorker:

In any play, however trivial, there has to be a still point of moral reference against which to gauge the action. In our lives, in the late nineteen-forties and early nineteen-fifties, no such point existed anymore. The left could not look straight at the Soviet Union’s abrogations of human rights. The anti-Communist liberals could not acknowledge the violations of those rights by congressional committees. The far right, meanwhile, was licking up all the cream. The days of “J’accuse” were gone, for anyone needs to feel right to declare someone else wrong. Gradually, all the old political and moral reality had melted like a Dali watch. Nobody but a fanatic, it seemed, could really say all that he believed.. . .

In those years, our thought processes were becoming so magical, so paranoid, that to imagine writing a play about this environment was like trying to pick one’s teeth with a ball of wool: I lacked the tools to illuminate miasma. Yet I kept being drawn back to it.

I came back to Miller’s commentary after reading Tre Johnson’s commentary in today’s Washington Post:

“Once again, as the latest racial travesty pierces our collective consciousness, I watch many of my white friends and acquaintances perform the same pieties they played out after Trayvon, Eric, Sandra, Korryn, Botham, Breonna. They are savvy, practiced consumers of Meaningful Things: They’ve listened to “Serial” and become expert critics of our broken criminal justice system after just one season. They’ve watched “Insecure” and can suddenly imagine life as Molly or Issa. They’ve shared the preordained “amplifying” social media post that just reads “This,” followed by a link to something profound from a black voice.. . .

“The confusing, perhaps contradictory advice on what white people should do probably feels maddening. To be told to step up, no step back, read, no listen, protest, don’t protest, check on black friends, leave us alone, ask for help or do the work — it probably feels contradictory at times. And yet, you’ll figure it out. Black people have been similarly exhausted making the case for jobs, freedom, happiness, justice, equality and the like. It’s made us dizzy, but we’ve managed to find the means to walk straight.”

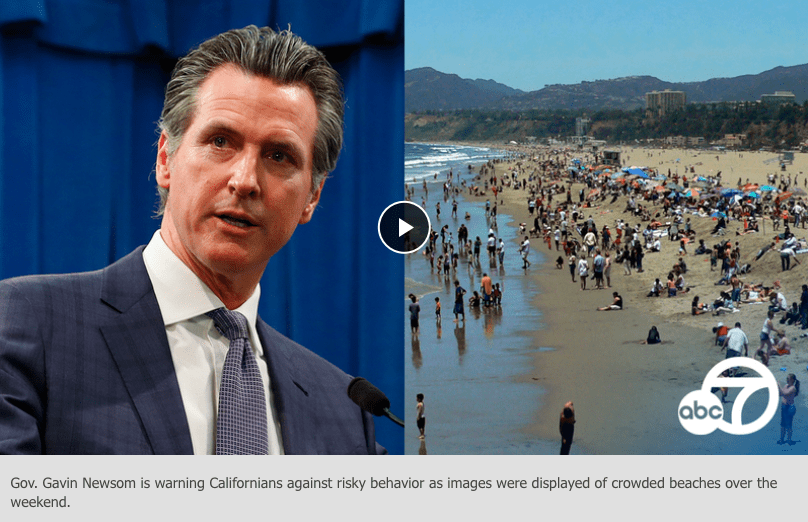

Johnson, of course, falls into the trap that everyone else has fallen into, but at least he sees the trap. The combined effect of COVID-19 “content” (what an odious word) and, once more, the merry-go-round of commentaries on yet another horrific racial tragedy, have filled the social media universe with exhortations: Stay the fuck at home! Check your privilege! Wear your mask! Look within yourself! Be a good ally! Educate yourself! Flatten the curve! Dismantle white supremacy! The electronic town square holds trials for the Karens and Beckys of our time, which, given the centuries-old racist marinade we have been submerged in, are never in short supply. Everyone has an opinion about those (me included.) Everyone has an opinion about someone else’s opinion (me included.) Lists upon lists crop up in our social media feeds: Rating activities as to how safe they are (followed by the obligatory argument that the writer refrains from all of them, out of an abundance of caution); do’s-and-don’t’s for protesting “properly” are modified. Well-meaning people sincerely ask whether their white children may raise a fist on TikTok and receive fifty replies, all different. The actual issues are buried under edifices upon edifices of performance, performance, performance. Meta conversations about performance are rabbit holes. Every day some celebrity or other wears something or says something or performs some physical gesture, providing more grist for the mill. Every horrific incident of violence, racism, or racial distress, every photograph of someone out of compliance with the pandemic mandate-de-jour, becomes a morality tale, fueling endless takes, opinions, and new lists of instructions. Pandemic prevention enforcement and “how to be a good ally” have linked hands and are now the new religion of social media. We are in a panopticon, but the Foucaultian roles are reversed: we sit in the watchtower in the middle, and all around us are bloviating pulpits.

(I realize this post is falling into the same trap of exhortation, but this underscores my point–there is no end to a sea of pointing fingers. It’s turtles all the way down.)

If we were half as busy actually doing world improving things as we are performing our goodness in the public square and moralizing others, we might be in a different place. But public image is everything, and “content” (there it comes again!) must be provided. Citizens United has come full circle: now that corporations can speak like people, people speak like corporations. Everyone is a public entity, and so everyone has to issue on-point “messaging” to the public. Jeff Skilling’s infamous statement, “I am Enron,” is now true for everyone. Performance comes before feeling or doing. We must be on brand.

The problem is that “the personal is political” works both ways. It is one hundred percent true that we all play a role not only in pandemic spread, but also in the perpetuation of white supremacy. It is one hundred percent true that every revolution starts with individuals, and that individuals have the power to change the world–especially when organized. But these truths obscure other truths. “Flatten the curve” and “dismantle white supremacy” are big, pompous, vague goals, and in the absence of responsible adults at the helm of the country, there are bound to be differences in how we, the people, parse them into everyday behaviors. We’ve missed the train on testing and contact tracing, and now we’re left to pick at each other for mask violations.

The incessant chatter, be it contrite, derogatory, or both, is not “doing the work” that we are told to do. It is performing the work, which is something else entirely. It is exhorting others to perform the work. All the world’s a stage, and on this particular stage, we are performing The Crucible 24/7. There’s no escape from watching, from participating, from fretting about participating lest our flawed goodness be exposed.

I deeply understand where the urge is coming from. There are good intentions. There is a desperate need to do something in a situation in which we feel particularly powerless; we are sheltering at home, our face-to-face meeting places are closed, this online discourse is a poor substitute to our in-person conversations. As more and more avenues to do good close, either because they are impossible or because they are severely criticized, we are clutching at straws. These bursts of personal propaganda are the best thing we have, and we figure they are better than nothing, because silence is also a problem. And most importantly, there is pain. Searing, unbearable pain and grief. Grief for the sick, grief for the dying, grief for the people being killed and injured and ostracized and ignored. Grief and guilt. It feels overwhelming to sit with it. We take to our keyboards to find some relief, to tell some story about it, to remove the center of grief from our hearts to our heads to our keyboard. But verbose descriptions of grief are not the grief itself.

Can we take an intermission? Not from the work itself–improving the world is the project of a lifetime–but from the performance of it? Can we stop obsessing about our goodness and the goodness of others? Can we stop “messaging” so that we can actually feel something? Can we quiet our nimbly typing fingers to listen to the cries of the world, of friends and neighbors born to disadvantage, of our dying planet? Can we quiet them long enough to hear our own hearts quiver in compassion?