As the first part in the blog’s vaccine education campaign, and following up on yesterday’s post, I’m very happy to offer you a Frequently Asked Questions document created by Drs. Leah Rorvig and Brie Williams with medical/scientific information about the COVID-19 vaccine from a source that 100% wishes you well and you can trust. Drs. Rorvig and Williams are active members of AMEND, the physician organization that issued the memo urging San Quentin to reduce its population to 50% of design capacity. Here goes:

COVID-19 Vaccines: The Basics

- Vaccines teach the immune system how to recognize and fight off the virus that causes COVID19, which can prevent vaccinated people from getting sick. Vaccines are not used to treat

people who are currently infected with COVID-19. - There are currently two vaccines available in the United States – one made by Pfizer and one

made by Moderna - The vaccines are both 95% effective at preventing illness due to COVID-19

- The vaccines have now been administered to millions of people and have a strong record of

safety - While the vaccines were developed in record time, they have gone through all of the same

steps required of any vaccine before it can be approved for use - Both vaccines have two doses, either three weeks apart (Pfizer) or four weeks apart (Moderna)

- The vaccine is given as a shot in the upper arm

Is the COVID-19 vaccine safe? Should I worry that the vaccine was made so quickly?

- Both vaccines were found to be safe and effective in tens of thousands of adults (including Bla

and Latinx people) who participated in high quality research – the same research that any new

vaccine or medicine must undergo before being approved. - Both vaccines were reviewed faster than normal, but this is because so many people are getting

sick and dying of COVID-19 that it is considered a national emergency. - Both vaccines have been authorized by the FDA (Food & Drug Administration) and the

California Department of Public Health. - In the U.S. alone, more than 5 million people have now received at least one dose of a COVID19 vaccine.

Has anyone died as a result of the COVID-19 vaccine?

- No one has died from the COVID-19 vaccine. More than 350,000 Americans have died from COVID-19.

What are the possible side effects of the vaccine? Should I be worried about them?

- The most common side effects of the vaccine are arm soreness, tiredness, headache, muscle

pain, chills, joint pain, and fever. These side effects are more common after the second dose of

the vaccine and – if they occur – usually resolve within 2 days. - These symptoms are normal and they are a sign that your body is building protection against

the virus that causes COVID-19. - Among the millions of people who have now received the vaccine, a very small number of

people have experienced severe allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines. If you have ever had a severe allergic reaction to a vaccine or other substance in the past, you should discuss this with

the health care professionals giving you the vaccine.

The COVID-19 vaccine is an mRNA vaccine. Does that mean it changes your DNA (also called your genetic code)?

- The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines both use “messenger RNA” (also called mRNA) to teach the

cells in your body to recognize the outside part of the virus that causes COVID-19. That way, if

you are exposed to the virus, your immune system will stop it from making you sick. - The COVID-19 vaccine does not change your DNA. mRNA is not the same as DNA, and it

cannot combine with your DNA to change your genetic code.

Can I get COVID-19 from the vaccine?

- No. Because of how the vaccine works, it is impossible to get COVID-19 from the vaccine. However, the vaccine prevents 95% (and not 100%) of COVID-19 cases. Even if you have been vaccinated, if you have a cough, fever, or other symptoms, then there is a chance you could have COVID-19, and you should ask to speak to medical staff right away.

I have hepatitis C and/or HIV. Is it safe for me to get the COVID-19 vaccine?

- Yes. It is safe for people with hepatitis C and HIV to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. There are very few medical reasons not to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

Do I need to keep wearing a mask after I receive the COVID-19 vaccine?

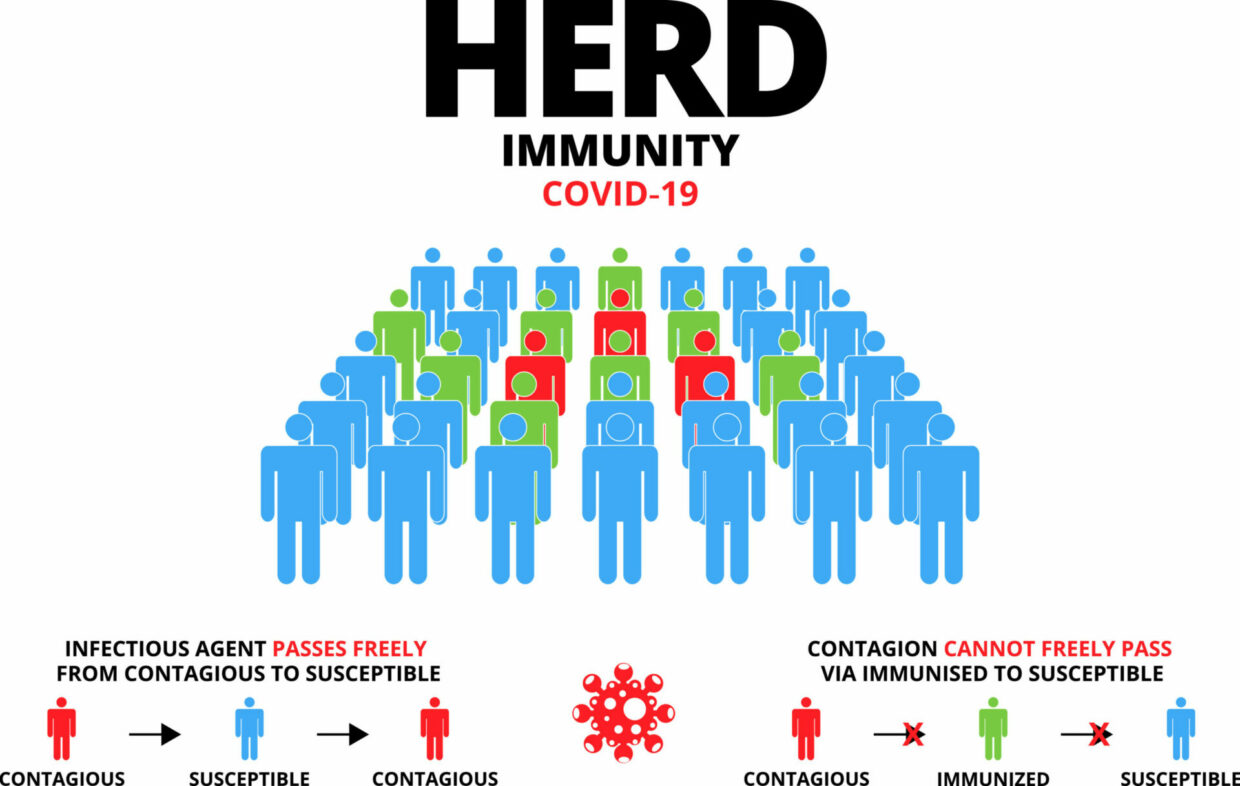

- Yes. Unfortunately, even people who have had the COVID-19 vaccine may be able to get infected, and although the vaccine protects them from getting seriously sick, they may spread COVID-19 to others. (We do not know how common this is yet.) Until the majority of people have been vaccinated against COVID-19, everyone needs to continue wearing masks, practicing physical distancing, and frequently washing their hands.

If I already had COVID-19, do I need to get the COVID-19 vaccine?

- COVID-19 vaccination should be offered to you even if you already had COVID-19

- COVID-19 vaccination has been shown to be safe in those who have already had COVID-19

- Right now, research shows that reinfection with the virus that causes COVID-19 is incredibly rare in the 90 days after you first get sick with COVID-19. Therefore, the vaccine should be offered to everyone, although some health systems are currently prioritizing patients who have not already had COVID-19 while the vaccine supply is very limited.

- You should not get the vaccine if you are currently sick with COVID-19.

Is the COVID-19 vaccine mandatory (required)?

- No, there is no mandatory vaccination requirement from either the state or federal government. While vaccine doses will be limited in supply at first, public health officials – and the team at AMEND at UCSF hope that by telling people about the safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines, we can encourage people to voluntarily take the vaccine. The AMEND team is all planning to get the vaccine and some of us have already gotten it!

I got the COVID-19 vaccine because I want things to go back to normal. When will that happen?

- We don’t know when enough people will be vaccinated so that things will go back to normal. But the more people that are vaccinated inside and outside of prison, the sooner things will begin to return to normal. Also, when you get the vaccine you protect other people around you by making it less likely for them to get COVID-19.

Did AMEND staff get the COVID-19 vaccine?

- Yes. All of the AMEND team members who see patients already have received the COVID-19 vaccine.

- Other AMEND staff will receive it as soon as it is available to them.

I heard the guards/officers, health care staff, or warden at my facility are refusing to get the vaccine. If they aren’t getting it, why should I?

- There are many reasons that people are afraid to get the vaccine. These include a lack of knowledge about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, a lack of understanding about COVID-19 itself, a long history of mistrust of the medical system, and more. We encourage you to empower yourself to learn as much as you can about the COVID-19 vaccine. It is important that you make your own decision about getting the vaccine regardless of what other people are doing. The team at AMEND and our partners on this FAQ all support vaccination. See above for a complete list of our partners.

I still have more questions, what should I do?

- You can ask your friends or family to get more information about the COVID-19 vaccines at these trusted sites:

- https://covid19.ca.gov/vaccines/

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/faq.html

- To learn more, you can also call the Transitions Clinic Network Reentry Healthcare Hotline to speak to a community health worker with a history of incarceration. Toll free, M-F, 9-5pm. Call: 510-606-6400.

- If you or your loved ones have additional ideas for questions that we can answer on this information sheet, please email us at info@amend.us or write to Amend, 490 Illinois St, Floor 8, UCSF Box 1265, San Francisco, CA 94143.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: COVID-19 Vaccination

- https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinical-considerations.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/faq.html

- State of California COVID-19 Vaccine Information Center https://covid19.ca.gov/vaccines/

- UCSF COVID-19 Vaccine Information Hub https://coronavirus.ucsf.edu/vaccines