The last chapter of our book FESTER, which is already out from University of California Press, is called “The Next Plague.” We wrote it to warn everyone in prison administration, prison litigation, and politics, that if considerable reforms are not sought–chief among which is an aggressive 50% reduction in prison population, which we believe is feasible without a corresponding rise in crime rates–the next plague will provoke calamities in the same way this one has.

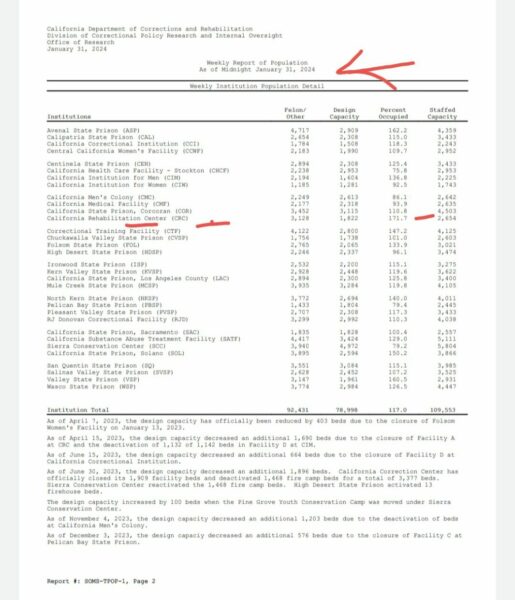

Two new pieces of information suggest that things are going the same way they had pre- and during COVID19. The first has to do with prison overcrowding and comes to me from the ever-attentive prison conditions activist Allison Villegas (thanks, Allison!) who diligently follows up the periodic population counts. Take a look at the latest:

Not only is the total number back up to 109,000–more than before COVID–but some prisons are so overcrowded that it looks as if Plata (which required population reductions to 137.5% capacity) never happened. Norco is at 171% capacity; Avenal is at 162% capacity. If Plata applied per individual prison, rather than system-wide (which would make more sense, as we explain in ch1 of FESTER), six prisons would currently be in violation of that standard. The entire system is at 117% capacity (design capacity is fewer than 79,000 people), Plata-compliant but not by much. This should never be the case if we are to maintain minimal healthcare standards and in many ways is the root of much of the evil we saw in Spring 2020.

The second piece of information comes from my colleague Dorit Rubinstein-Reiss. It is a Ninth Circuit decision regarding government accountability for the COVID vaccination fiasco in Oregon prisons, which you can read verbatim here. The lawsuit was brought by people incarcerated in Oregon, and claims that, during COVID-19, they were categorically assigned to a lower priority vaccination tier than correctional officers. In FESTER, we document a similar struggle in California, where the California Department of Public Health initially scheduled incarcerated people to receive the vaccine in tier A2, and then scratched that, to everyone’s amazement. At work, as we explain in the book, and as I explained in this op-ed, was a misguided zero-sum mentality that vaccines in prison somehow come at the expense of vaccines to other people–when, in fact, prisons and other congregated facility acted as incubators and loci of superspreader events. But here in California, the struggle was that, though prison guards were prioritized for the vaccine, they refused to take it, and their union was willing to go all the way to the Supreme Court to fight against it, with Gov. Newsom and AG Bonta’s support. We lost that fight, which is shameful, and this Oregon case is yet more proof of how and why the house always wins these kinds of lawsuits, no matter how meritorious they are: in this case, it turns out that Governor Allen and other state officials have immunity against the lawsuit that stems from the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (“PREP”) Act.

Here’s how the parallel fight went down in Oregon:

The Oregon Health Authority then published guidance recommending phased allocation of the vaccines. In Phase 1A, healthcare personnel, residents in long-term care facilities, and corrections officers were eligible for vaccines. In Phase 1B, teachers, childcare workers, and persons age 65 or older were eligible. Neither phase categorically covered adults in custody (“AICs”), but AICs who met the eligibility criteria were prioritized for vaccination on the same terms as the general population. For example, all AICs who were 65 or older were eligible for vaccination in Phase 1B. The Governor’s initial rollout of the vaccines was consistent with OHA’s guidance.

In response, Plaintiffs amended their complaint to add class claims for injunctive relief and damages, alleging that the vaccine prioritization of corrections officers, but not all AICs, violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. On February 2, 2021, the district court certified a provisional class of all AICs who had not yet been offered a vaccine and granted Plaintiffs

preliminary injunctive relief, ordering the immediate prioritization of approximately 11,000 AICs for vaccination. Defendants complied with the court’s order.In September 2021, when vaccines were no longer scarce, the district court dismissed as moot Plaintiffs’ claim for injunctive relief because all Oregonians (ages twelve and over) were eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine and vaccine supply in Oregon exceeded demand. Plaintiffs’ damages claims, however, remained.

Get it? After everyone got sick and died, then the vaccine was available, but by then, of course, the claim was moot. But even the revival of the case is of no avail, because the Ninth Circuit “conclude[s] that the vaccine

prioritization claim falls within the scope of covered claims because, under the PREP Act, “administration” of a covered countermeasure includes prioritization of that countermeasure when its supply is limited.”

This is exactly the point we make in FESTER. What with prevarications, immunities, and continuances, courts adjudicating prison health matters as such are the worst place to seek justice in a timely manner. And since politicians know that protecting incarcerated people, particularly those who are old and infirm, is never an electorally wise move, and that shortchanging and sandbagging the prison population can happen with immunity, how is there ever going to be motivation to vaccinate and decarcerate, the two things that must happen the next time a big one comes along?