(all images by Tom McGee; click on graphics for clearer, larger image)

(all images by Tom McGee; click on graphics for clearer, larger image)

Thank you for your blog, California Correctional Crisis. Your posts have been especially helpful.

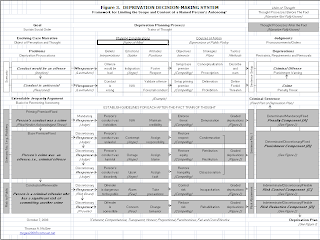

I am sending this email, rather than posting a comment, because I wanted to enclose an attachment, which was prepared using Excel. It is a chart depicting a proposed Deprivation Decision-Making System. I believe that sentencing should be put in this broader context. You will see that it makes provision for both determinate and indeterminate courses of action. The Mixon matter you have been writing about is a good example of why something like this is necessary. Of course, I do not have access to his case history, but since he was classified as a high-control parolee, there must have been evidence that he was a high risk. Under the system I propose, Mr. Mixon would have completed the accountability part of his Deprivation Plan. But he would not have been moved to a lower level of restraint, because he had a high level of risk.

I know that risk determinations are contentious, but risk is a fact of life. Insurance companies deal with it all the time. It is not possible to predict with complete certain ty who will commit another crime, or what kind. But it is possible to estimate the probability that a person will recidivate,within a probability range. Policy makers have to decide how much risk is acceptable. If risk determinations do not reach a legally acceptable standard, then lets say so and act accordingly, rather than hiding this in some kind of sentencing double-talk.

Just one more point; I think it is ridiculous to ask judges to consider risk at the time of sentencing. Risk changes. Who can say today what an offender’s risk will be five years from now. A Risk Control Board should make periodic risk determinations of this kind. Parole Boards as we knowthem are not equipped for this task.

I would appreciate any comments you may have about the enclosure, and these comments. Again, thanks for the blog.

************

One of the interesting things about Tom’s model is that it incorporates quite a multifaceted perspective on offenders and their motivations. One key dilemma in modeling and predicting human behavior has to do with the difficult trade-off between accuracy and simplicity. That is, the more complex the model is , the more accurately it can predict risk, but the more difficult it will be to apply. More on this in future posts.