It’s been a month since I posted here! Life is thick with responsibilities and joys–family, athletics, spirituality, the daily grind of work–and so I haven’t had a chance to come up for air. But I wanted to briefly comment on a recent Chron story that one of my students (thank you!) sent me. It involves an unusual request by San Francisco’s D.A., Brooke Jenkins, to solicit federal cooperation in a matter involving two men accused of (unrelated) heinous crimes who are currently abroad, having fled our jurisdiction: she wants them extradited and tried here in San Francisco.

The simple and accurate response to this is exactly the one that Supervisor Aaron Peskin, often the voice of reason on the Board, voices in the article:

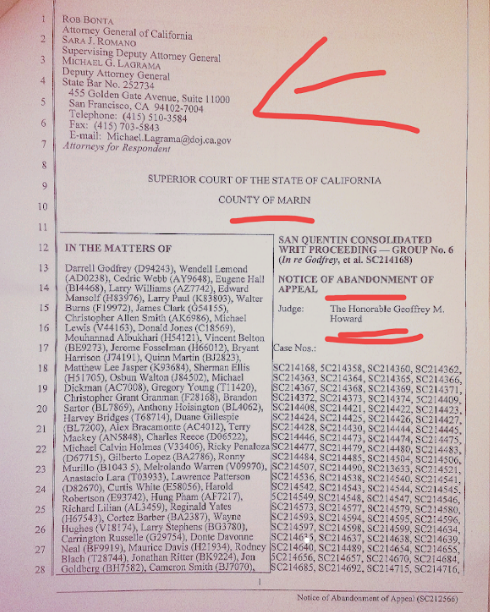

[T]he waiver Jenkins is pressing for is unnecessary, because nothing in San Francisco’s sanctuary city law prevents Homeland Security from apprehending and extraditing the two fugitives so that they can be prosecuted in San Francisco. He added, moreover, that the board would have to approve an ordinance to grant the exception, which means it would have to be debated in committee, subjected to two board hearings, signed by the mayor and set on the books for 30 days before taking effect, in late March at the earliest.

By contrast, he said, “the feds can apprehend these people tomorrow.”

I feel like I need to highlight this because, in my circles and more generally, there seems to be an exaggerated sense of the protections that sanctuary cities or states can afford undocumented immigrants and other noncitizens. It seems we have forgotten the Trump days in which ICE personnel roamed the streets of the Mission looking for potential people to deport and we all had our cellphones at the ready in case someone was nabbed off the streets and needed help. They were not doing anything unlawful; they were doing something meanspirited and cruel, which is a completely different problem. While the federal government and the state of California are two separate sovereigns, they do operate in the same physical territory, a little bit like China Miéville’s book The City and the City. We don’t have to cooperate with them, but we can’t stop them from operating throughout the same geographic space on their own accord.

This has a few important corollaries. First, it is one more example in which the concept of geographic space needs to enter the criminal justice conversation. I have high expectations of carceral geography as a field of study, but I worry that it’s become basically like sociology of punishment with more abstruse jargon and a lot of metaphor, when there’s lots to be said about the practicalities of physical space. In that respect, our forthcoming book FESTER espouses a really pedestrian understanding of geography with immediate practical implications: you can’t treat prisons as if they exist apart from their surrounding counties when a deadly pandemic is on the loose. The same spatial problem, also with eminently practical implications, is present in the sanctuary city context: if you operate in the same space as someone you don’t cooperate with, at some point you will collide, and you’ll have to figure out how to work out the collision (in Miéville’s book, by the way, these situations require a third police force, called “breach.”)

Second, and related, people tend to forget the many points of contact between local and federal justice that cannot be avoided even with the most assiduous sanctuary city laws, and even if everyone on the local level religiously complies with them (some don’t.) Anytime someone is arrested, their fingerprints find their way into a federal database, where they are matched with the people who are here lawfully. If they are not, it’s not particularly challenging to figure out where they are. If local jail authorities will not allow ICE into their facilities (which, under sanctuary state/city laws, is okay), ICE officers can ambush noncitizens who are heading to meet their probation officers and arrest them in the parking lot. ICE holds on people serving state sentences are lawful and, the minute the person exits the state facility, they will end up in the feds’ hands.

The only thing limiting federal intervention is the extent to which the feds are interested in intervening, which is a direct function of presidential policy. Removal rates in the Biden era were much lower than in the Trump era. During the Obama era, they were fairly high, but federal policy emphasized people convicted of serious crimes, whereas under Trump there was the deliberately inflammatory persecution of DACA recipients (some of the most upstanding Americans I know.) Who gets targeted, and how many get targeted, is purely the function of who is president and what they (or their constituents) care about. This is stuff that local authorities can do very little about, given the many interfaces these systems share.

Legal historian Karl Shoemaker, an acclaimed Medieval historian and fellow JSP alum, wrote a fantastic book about the legal and moral rationales behind sanctuary in the Middle Ages and its decline toward the Early Modern period. As Shoemaker explains in the book, during these times, in which ecclesiastic authorities governed the legal universe, claiming sanctuary truly meant escaping any legal responsibility for one’s crime. It is no coincidence that these rationales, which seeped into British common law from ecclesiastic law, faded in the Sixteenth century, with the advent of the idea of a secular state.

The key to understanding the feeble protection that sanctuary state laws offer our noncitizen friends and neighbors is to remember that, back in the Middle Ages (and certainly in Biblical times, whence the idea of sanctuary emerged,) there were no competing secular jurisdictions jockeying for position. What we call “sanctuary” is a far cry from the ironclad religious protection of yore, and would be better described as “noncooperation” with a legitimate sovereign occupying the same physical space. Can the feds find these two men who are accused of heinous crimes, see to their extradition, and hand them over to Brooke Jenkins? Sure. The question is whether they want to.