A couple of days ago I spoke on KCRW about the announced closure of death row at San Quentin. Here’s the story as it appeared on the KCRW website, followed by some additional thoughts from me:

***

Governor Gavin Newsom announced this week a plan to shut down the notorious death row at San Quentin State Prison. The plan would move the prison’s most condemned inmates to other maximum security prisons over the next two years, in an effort to create what Newsom calls a “positive and healing environment” at the Northern California prison.

San Quentin has the largest death row population in the nation — nearly 700 total. And while California hasn’t executed anyone in more than 15 years, Newsom also signed an executive order imposing a moratorium on executions in 2019.

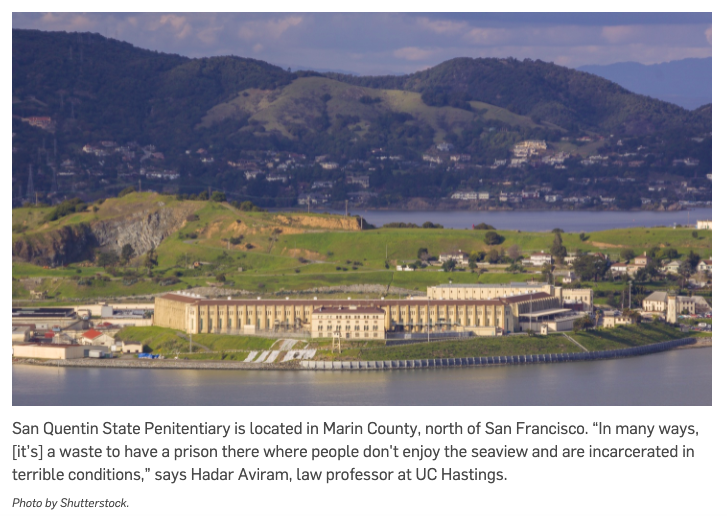

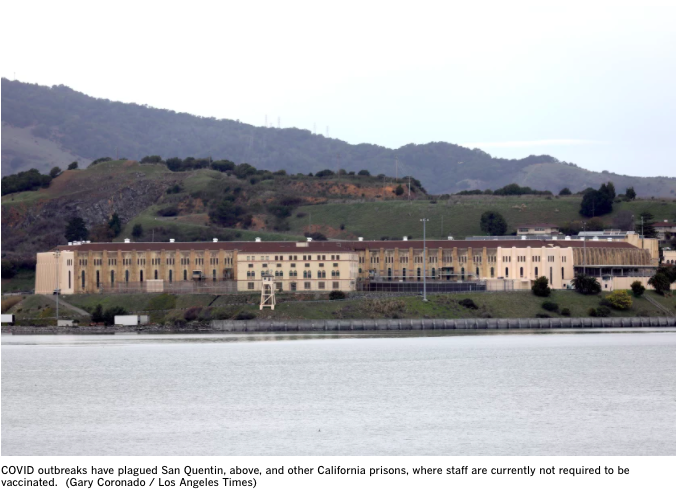

The facility was originally a ship, and in the mid 19th century, prisoners themselves built the prison, explains UC Hastings law professor Hadar Aviram. “It’s a dilapidated facility, there are no solid doors, there are bars on the doors, ventilation is terrible. So it’s a facility that was built for 19th century standards. And just because of inertia, we are still incarcerating people in the same condition.”

She points out that the facility is located in a geographically beautiful area surrounded by expensive real estate. “In many ways, [it’s] a waste to have a prison there where people don’t enjoy the seaview and are incarcerated in terrible conditions.”

However, she notes that people currently aren’t being executed due to the moratorium, and since 1978, the state executed only 13 people, and more than 100 died of natural causes during that time.

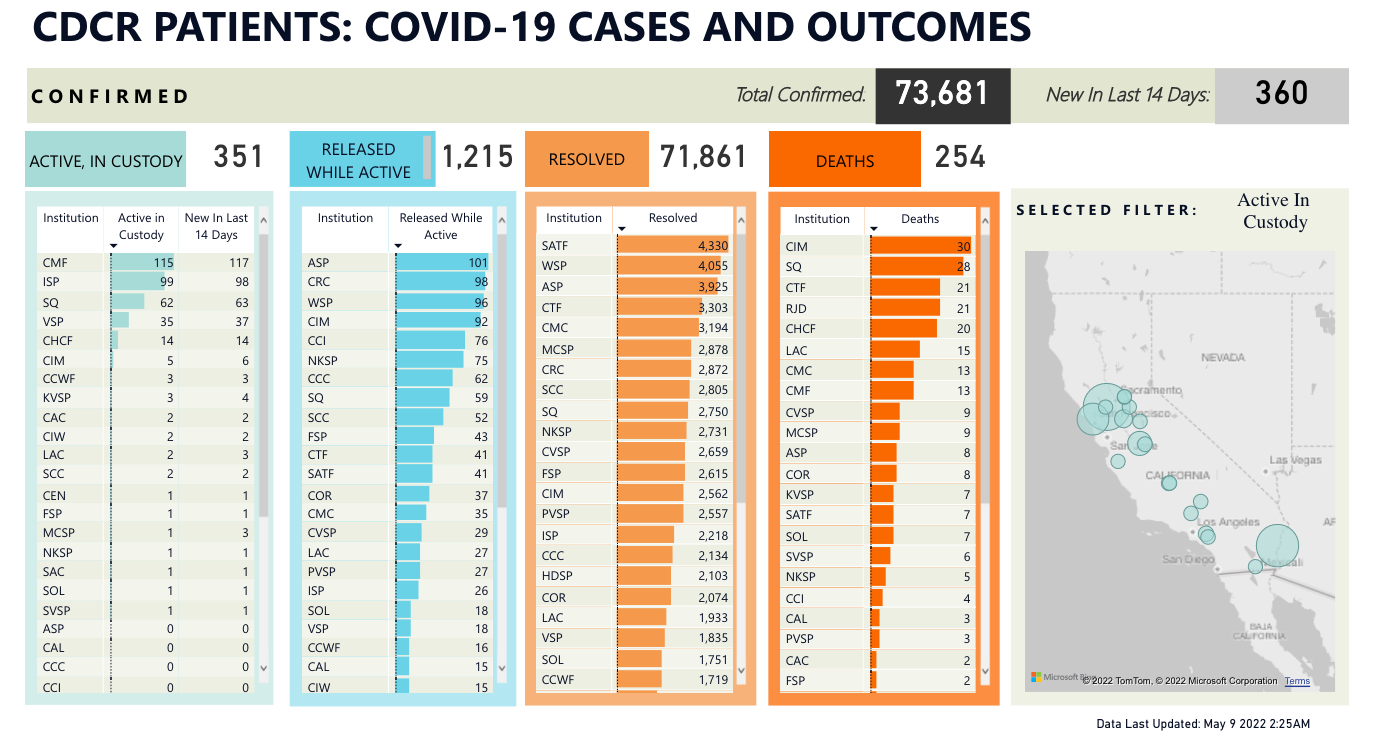

“Just during this moratorium that Governor Newsom introduced, more people died on death row from COVID during the horrific outbreak at Quentin than we executed since 1978. So I’m sure that is giving some pause about the utility of the exercise of keeping people there,” Aviram says.

Because San Quentin is so old, inmates there suffered from coronavirus more than those at modern and well-ventilated facilities like the state prison at Corcoran, she says. Plus, it houses lots of people who are aging and infirm, who were thus already immuno-compromised and vulnerable to the virus.

Emotional and political reasons may be driving votes

California voters approved a ballot measure in 2016 to speed up executions, and the measure included a provision allowing death row inmates to be relocated to other prisons where they could work and pay restitution to their victims.

Aviram says over the years, there have been several attempts to abolish the death penalty through voter initiaties, but they always lost by small majorities.

Through inquiries, polls, and conversations with people, she says she realizes: “People are voting for the death penalty largely for emotional, sentimental, political reasons. They are more in love with a fantasy of having a sentence that’s reserved for the worst of the worst, and can deter people.”

She describes death row in California as “basically a more expensive version of life without parole that costs us $150 million a year.”

She adds, “It’s probably a good idea to think of the death penalty as undergoing the same process as some of the people who have been sentenced to death, which is rather than an execution, the death penalty is going to die a slow natural death itself, just from disuse and from this gradual dismantling.”

However, some district attorneys continue asking for the death penalty in capital cases, though the state doesn’t execute people anymore, as they hope the governor might revive the policy, Aviram points out. However, she says, “I think that because of the national trends … it is extremely unlikely that it’s going to come back.”

Newsom’s reimagining of prisons and what’s missing

When the governor says a “positive and healing environment,” Aviram says this means a life where inmates find meaning and usefulness (do some jobs).

But this doesn’t completely eliminate the death penalty, she says. “Because there is still one very big and expensive piece of the death penalty that is still with us — and that’s death penalty litigation.”

“We have this facility where people are sentenced to death and are still litigating themselves post-conviction, and that litigation is actually the lion’s share of the expense. So it’s only really going to go away if and when all of those sentences are commuted, and these people are no longer litigating their death sentences at the state’s expense. So that is the missing piece.”

***

Some more thoughts: First, it’s been interesting to follow the fanciful, but often idle, talk about the real estate potential of Quentin. Readers who have been to Quentin know how beautiful the village is and how glorious the waterfront vistas are. There are plans to close four prisons, but no definite plans for Quentin. Any prospects of selling that land are to be viewed with ambivalence. On one hand, what a waste to have a prison so close to the water, without windows to enjoy the view – a place that combines suffering with beauty. On the other hand, it would be a terrible loss for the folks housed at Quentin, dilapidated and dangerous as it is, to be strewn about prisons in remote locations in the state, far away from the progressive energy of volunteers and rehabilitative programming richness of the Bay Area that people so desperately need for making parole. In my wildest fantasies, we close Quentin down, transform it into a resort/retreat for nonviolent communication and community healing, rebuild with huge ceiling-to-floor glass walls overlooking the ocean and gorgeous walking trails, and offer all the men well-paying jobs running the resort.

About the money: I predicted much of this demise, based on national trends, in Cheap on Crime, and still think that the deep decline of the death penalty is in no small part due to the financial crisis of 2008. The fact that we still spend a sizable pile of money on death row, despite the moratorium, is not surprising, and shows that the disingenuous efforts to save money via Prop 66 didn’t fulfill their purported purpose. In 2016, when giving talks about this, I used to draw the triangle of home improvement; write in its three corners: good, fast, and cheap; and tell people, “you can have two.” We can’t compromise on having a “good” death penalty (one in which there are no constitutional violations and factual mistakes), and so, it cannot be fast or cheap. The big savings will only roll in when we get rid of the litigation piece.

There’s no better proof that the death penalty is on its last leg than the fact that Joseph Diangelo, the Golden State Killer, was sentenced to life without parole. If not the most notorious and heinous criminal in the history of California, then who? And the logic in Diangelo’s case applies to everyone else–why the death penalty? So they can continue litigating at the state’s expense and die a natural death? Whose interests does this serve?

About the actual job of relocating death row people to other prisons/general population: this is going to be a complicated and delicate job, and my fear is that it will be entrusted to folks who are not tuned in to the complexities. They would be moving people who have been effectively “at home” in solitary confinement in unique conditions, many of them for several decades, into facilities with much younger people and a very different energy. There could be animosities and alliances that are difficult to predict and go beyond crude racial/gang affiliations. This is true, generally speaking, for every prison transfer (long time readers remember the fears and concerns surrounding CDCR’s plan to comply with the landmark decision in Von Staich through transfers to other facilities); in the case of the death penalty, there are other factors, not the least of which is the unique combination of notoriety and frailness of the people to be transferred.

There’s also the question whether dismantling death row, what with its symbolic hold over the Californian imagination, slows down the dismantling of the death penalty itself. Without the physical reminder of the remnants of this archaic punishment, and with the growing resemblance of the death penalty to the two other members of the “extreme punishment trifecta” (life with and without parole), does the effort to abolish the death penalty lose its steam? The uphill battle for activists will be to spin this development to argue that the death penalty has been defanged beyond its utility; now that we’re left with only its negative aspects (to the extent that some people think it has advantages) it’s time to stop hemorrhaging state funds for incessant litigation.

***

Today I’m at the Annual Meeting of the Western Society of Criminology, speaking about FESTER. My panel starts at 8:15am island time in the Waianae room – come say hi!