My circle of Israeli friends is rattled by the exposure of sexual misbehavior by acclaimed actor Erez Drigues, who has now taken some responsibility in a much-discussed interview. Meanwhile, my circle of U.S. friends is reacting to the new documentary about Woody Allen. The ensuing conversation is conflating two separate questions, the moral and the factual one, namely: what my values are and who I believe.

I get why the two questions get conflated. In the New Salem, every news story becomes a morality tale. We incessantly opine on the behavior of strangers, as exposed in cellphone videos or tweets, and then we incessantly opine on the opinions of others. The marketplace of ideas has become the marketplace of moral arbitrage (I’ve recently discovered AITA on Reddit and can attest to the attraction, temptation even, of moral opining as a public exercise.) Moreover, because of the publicity of this opinion fest, it also serves an important performative role: who I support when I have the talking stick becomes a proxy of who I am, leading to destructive mobs and pileups, as John McWhorter explains in his new series about The Elect. This, in itself, is exhausting–the combination of constant condemnation of others and constant vigilance of being condemned is not a good way to live–but it becomes especially pernicious when we deal with things we don’t know for certain.

In Yesterday’s Monsters I wrote about the immense hubris that accompanies the major decision of the parole board in every case, i.e., whether the parole hopeful has exhibited sufficient “insight” about their bad behavior. A big part of this nebulous determination is vested in the question whether the person’s remorse for their past crimes is sincere, and the commissioners, who are very certain of their ability to detect sincerity, are also deeply professionally invested in being regarded as having the skills to tell the truthful from the liars:

During my work on this manuscript, I attended a social gathering in which I met a CDCR employee and a formerly incarcerated journalist. Conversation turned to the question of sincerity, and when I described my findings, the CDCR employee said: “If you were actually in the room, you’d be able to see body language and other nonverbal cues. That’s what the commissioners go on when they assess sincerity.” The journalist chuckled softly and replied, “you know, we saw a lot of people coming up before the board, and we knew what they were about in prison—who was real and who was just putting on a show. And often we would shake our heads when someone we knew was faking it got his date.”

In addition to reading the hearing transcripts, I watched some video footage of the hearings. If there was a telling nonverbal dimension to the inmates’ demeanor, I did not discern it. The footage left me unable to determine whether the remorse they expressed—often tearful and quiet—was genuine. Given the commissioners’ backgrounds, it is hard to imagine what psychological tools or expertise they possess that would enable them to detect the sincerity of the inmates. This is especially worrisome given the universal tendency to overestimate our lie-detection abilities. In a recent experiment, police officers and ordinary citizens were presented with videotaped confessions—some true, some false. The officers expressed more confidence in their ability to detect false confessions. The study found that police officers did worse than the ordinary citizens in distinguishing between true and false confessions.

In other words: There is robust empirical evidence to support the fact that we are very bad at detecting sincerity–and those who are most sure of their lie-detection skills make the most mistakes. Even lie-detection professionals like Paul Ekman, who stand by their ability to detect lying via facial micro expressions, agree that untrained professionals fail miserably at detecting lies.

Most of the time we do not have incontrovertible proof about incidents we did not ourselves witness (and sometimes, not even about incidents we did witness)–so we fill in the gaps with our values and world views, as work by the Cultural Cognition Project confirms. This is especially true in cases of sexual misbehavior, in which the factual question of the probability of truth-telling has become inexorably linked to whether one is pro-women or anti-women. Much of the discussion in the Drigues and Allen situations, as in many others, revolves around the likelihood of false complaints. Statistics that have no solid empirical grounding are banded about. In her book Unwanted Advances, Laura Kipniss cites Edward Greer’s law review article, in which he tries to figure out where the statistics about the rarity of false complaints come from. Kipniss retells Greer’s journey:

The 2 percent false rape allegations has been a huge article of faith among campus activists (and Title IX officers, I suspect), so frequently quoted that no one bothers to ask where it came from—until a legal scholar named Edward Greer published a rather gripping statistical whodunit in 2000, about his attempts to track down the source of the stat. His first discovery was that though the 2 percent figure was endlessly cited, every single citation ultimately led back to Susan Brownmiller’s 1975 book, Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. Yet Brownmiller’s notes provide a rather obscure source for the figure: a speech to the New York Bar Association by an Appellate Division judge named Lawrence H. Cooke, delivered in 1974.

Greer contacts Brownmiller: where did this information about the (now-deceased) judge’s speech come from? Brownmiller cooperatively combs through her decades-old files—Greer credits her with being “a very meticulous and organized writer”—and sends him a copy of the judge’s photocopied speech. The speech quotes the “Commander of the New York City’s Rape Analysis Squad” as having determined that “only about 2 percent of all rape and related sex charges are determined to be false.” But what was the judge’s actual source? Greer wonders. Was there some sort of official report or press release? Greer contacts the then-judge’s former law clerk, who cooperatively contacts a few other clerks who worked on the judge’s talk twenty-plus years earlier. None recollects any report.

Greer speculates that the judge may have been quoting a newspaper report, and he sets about trying to locate it, combing through local and national papers. He eventually finds a New York Times Magazine article titled “Rape Squad,” published two weeks after the judge’s talk, about a New York City police squad involved in a rape statistic–gathering operation. This squad was exclusively composed of police, however—trained in judo, not social science, notes the Times reporter. Though Greer can’t find any press release on the squad, he does manage to establish that the Times reporter happened to be a friend and neighbor of Brownmiller’s—she’s mentioned in Brownmiller’s memoir (Greer really is an amazing researcher). Were Judge Cook, Brownmiller, and the Times reporter all drawing on the same unknown source? Brownmiller gets a little defensive when Greer presses her on it.

The answer may be “lost to antiquity,” Greer finally concludes dejectedly, though what he’s established with certainty is that the famous 2 percent statistic, what one feminist scholar calls a “consensus fact,” derives from a single police department unit over forty years ago, and there’s no other published source for it.

It looks like, at minimum, we can’t fetishize these statistics. And at the same time, any effort to resolve things at the value level–such as the “transformative justice” gymnastics that are now so popular in the sex-positive community–inexorably boils down to the credibility question, much as one would like to circumvent that question or paper over it with jargon.

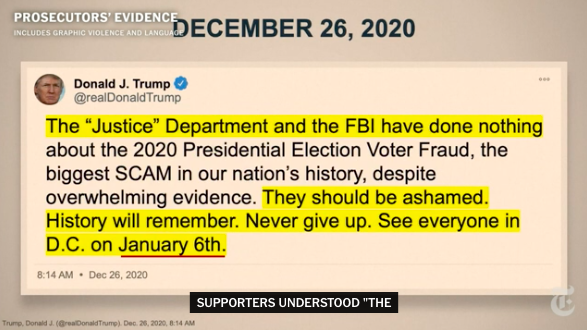

So how do we decide who we believe? At least in the Kavanaugh/Blasey-Ford faceoff, I recurred to what I know of my own experience to fill in the blanks (and wrote about it here.) Because Blasey-Ford (who is a complete stranger to me) and I come from the same milieu–we dress similarly, live similarly, talk similarly, do similar things for a living–I assumed that her cost-benefit calculus would be similar to mine, and I can tell you that I would have absolutely nothing to gain, and everything to lose, from making public claims of sexual victimization. Because this is so obvious to me, I would never make such claims unless (1) they were 100% true and (2) a civic matter of crucial importance was at stake. I imputed my calculus to Blasey-Ford whom, again, I don’t know from Adam, but I maintain that my extrapolation was probably more accurate than Trump’s: When Trump claimed that Blasey-Ford had accused Kavanaugh out of fame-seeking, that told me that he understood nothing about Blasey-Ford and her milieu, and it also taught me volumes about Trump and his milieu (and why someone like him would falsely accuse everyone on the planet on the regular.)

I assume that the range of opinions about Drigues, Allen, and countless others are an extension of the same principle. People’s worldviews inform their perspectives on whether they can imagine themselves falsely complaining, and they impute their perspectives to complete strangers. People who are like us couldn’t possibly fabricate a complaint, right? Because we are good! But those other people, on the other side of the political/social/cultural divide, they are nothing like us, and so it’s easier to imagine them lie. Either way, we are engaging in a subjective imagination feat: we can never know for certain whether a stranger in some scenario we read about in the news has the same cost/benefit calculus as us.

Another issue that I’ve noticed is the fact that my support or rejection of someone’s version of the events says something about me generally, or more particularly, about how I plan to live my life onward. This can be especially complicated when the accusation of a celebrated artist brings up the discomfort of enjoying a person’s art while suspecting that they did something atrocious. Because we now have moral edicts about finding flaws in artistic creations in the aftermath of discovering bad things about their creator,s some might choose to disbelieve the accusations of the artist so that they can continue to enjoy the art (disclosure: I adore Woody Allen’s movies and Louis C.K.’s comedy.) This problem is especially palpable when the suspect’s creation is co-shared with people who are still revered, or even who are themselves his accusers, as in the case of Joss Whedon and Buffy. If we could give each other a break from the moral sanitation process–the cleansing of the public square from any artifact whose creator has been suspected of being offensive–people might be less married to their defense of the creator.

Which brings me to the grim conclusion: Friends, we’re going to have to accept the fact that, on countless occasions, we will hear conflicting versions of the same incidents and we’ll have no way to determine for certain which is the correct version (or, as I learned in my military public defender days, that two people can walk away from the same incident with disparately different experiences and be both telling the truth.) For those of us who have to determine credibility and plausibility (judges and jurors) living with this difficulty is a part of life, for a career or for a particular trial. Also, when someone we know is the accuser or the accused, we’ll be called upon to stake our faith in them (I can tell you that, when I worked as a defense attorney, it was very important to our clients that we believe them.) The rest of us might have to learn to accommodate the somatic discomfort of Not Knowing.

Where does the discomfort come from? In the legal system, reasonable doubt should resolve itself in favor the defendant (I say “should” but things are more complicated than that.) But in your own heart, you don’t live “in the legal system.” If you don’t know what happened, it doesn’t support either of the versions. You are just living in groundlessness and doubt. This creates a tension within you that you feel you must resolve–and yet you can’t, not completely. I suspect that much of the conviction on both sides comes from the fact that everyone just wants to get rid of the dissonance already, so they sound more resolute than they are. But a big part of aging, for me, has been learning that I know much less than I think I know. It turns out that, unless you are a factfinder or put in a situation that requires your personal allegiance, you are allowed to say “I don’t know,” take a breath, look within yourself at how it feels not to know, and learn to live with it. And that’s okay.