In her 2018 book Building the Prison State, my colleague Heather Schoenfeld provides a retrospective of the incarceration explosion in Florida. The root of the problem–the situation that facilitated the astronomical growth in Florida’s correctional apparatus–was no other than Costello v. Wainwright, a prisoner’s rights case that focused on remedying prison overcrowding.

To understand what happened in Costello we must keep in mind that Florida’s population grew by two million throughout the sixties. That, in combination with an actual rise in crime and the emergence of new, Nixon-sponsored policing techniques, meant that between 1968 and 1972 the prison population grew by 31 percent. This resulted in the horrors and indignities of overcrowding with which we are very familiar in California.

Civil rights attorney Toby Simon, who represented the prison population in Costello, wanted to pursue change–but so did the prison warden. Wainwright was amidst a modernization project, and saw the overcrowded and outdated facilities as hurdles in his path to implement more rehabilitative programming behind bars. Finally, in 1979, a consent decree was reached: Judge Scott ordered a population reduction, and left the method to the state’s discretion. Since the entire Florida system was overcrowded, Wainwright was unable to reduce overcrowding by moving inmates from facility to facility. He had two available courses of action: releasing prisoners (via good behavior or parole) or increasing capacity (via building more prisons.) The consent decree gave equal weight to both strategies.

You can guess what happened: the consent decree gave discretion to the wrong people at the wrong time, and the choice was cynically exploited. Politics in Florida took a decidedly conservative turn, and in the ensuing law-and-order atmosphere, releasing inmates was a non-starter. More prisons were built, and the ensuing outcome followed the classic line from Field of Dreams: “If you build it, they will come.”

Throughout the book, Schoenfeld emphasizes that the disastrous outcomes of the implementation of Costello could have been avoided. I’m not sure I’d go quite that far; I worry that implying that civil rights attorneys have to take into account the cynical exploitation of vaguely decided victories could have the undesirable effect of discouraging them from pursuing remedies for the prison population. But here’s where I completely agree with Schoenfeld: the combination of judicial remedies open to discretion and interpretation with bad-faith actors looking for loopholes because of concerns about political expedience and posturing can be, and indeed has been, poison.

There are important differences between California and Florida, and between the situation in the post-Costello 1980s and the post-Von Staich scenario we have now. But there is an important similarity, and it is this: Population reduction orders that offer the correctional apparatus the option between releases and something else pretty much guarantee that the correctional apparatus will scramble to do the “something else.” In the situation we’re facing now, we’re not going to build new prisons (I think), so instead, in the next few days, we are likely to see CDCR playing a lot of Tetris with human lives.

I would like to caution as emphatically as possible against this course of action. It’s obvious from the decision in Von Staich that this is not what the Court wanted. The opinion didn’t go on and on about elderly, infirm people who have done decades in prison for violent crimes for no reason at all. Would it really hurt so much to consider this? What would be the downside?

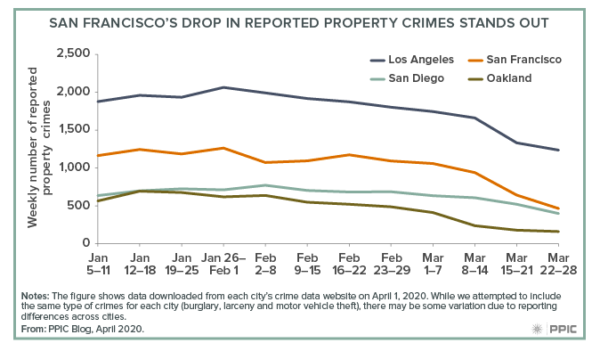

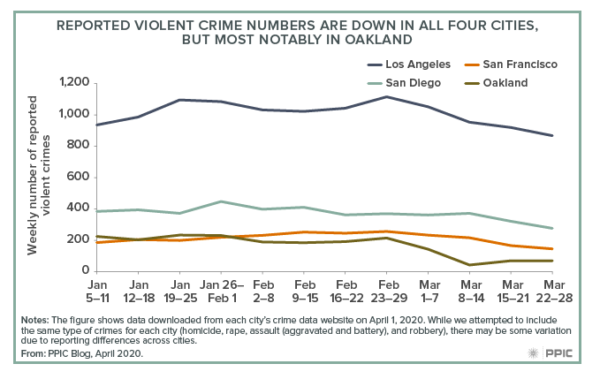

Honestly, this is what I think truly worries CDCR officials. As California gradually reopens, we are bound to see somewhat of an uptick in street crime. Crime rates in California, as elsewhere in the nation, are at their lowest rates since the 1960s, and they were further impacted by COVID-19, because the need to shelter in place changed the opportunity structure for committing crime. There are considerably fewer burglary and car break-in opportunities with everyone at home and vigilant in their neighborhoods. Violent crime (with the exception of stress-exacerbated domestic violence) is also down.

It strikes me as a pretty solid prediction that, as the state continues to reopen, these numbers will reverse themselves to a small degree–regardless of who and how many people are released from prison. But there is the very real concern that the media might foment public hysteria about rising crime rates and tie them causally to releases. You will recall that the same thing happened after Realignment (hysteria, no corresponding rise in crime), Prop. 47 (hysteria, no corresponding rise in crime) and after Prop. 57 (hysteria, no corresponding rise in crime.)

Against the tendency to do the political expedient thing, the only thing to do is to exhort our state officials to be responsible adults and rein in CDCR’s appetite for playing Tetris with human lives. The most tragic outcome of Von Staich might be a choice to round up the young and healthy folks and transfer them, untested and unsequestered, to another prison, where this catastrophe could play out again. Even if we get lucky, and it doesn’t, it leaves the older, more infirm people in a facility that is ill-equipped to serve their health needs. What we need is a tribune who will do the right thing and stop this predictable-but-counterproductive pattern from playing out. I think Gov. Newsom can be that tribune, and I urge him to exercise his power to make real, lasting change.